As Election Madness Climaxes: The Birth of the Modern Campaign

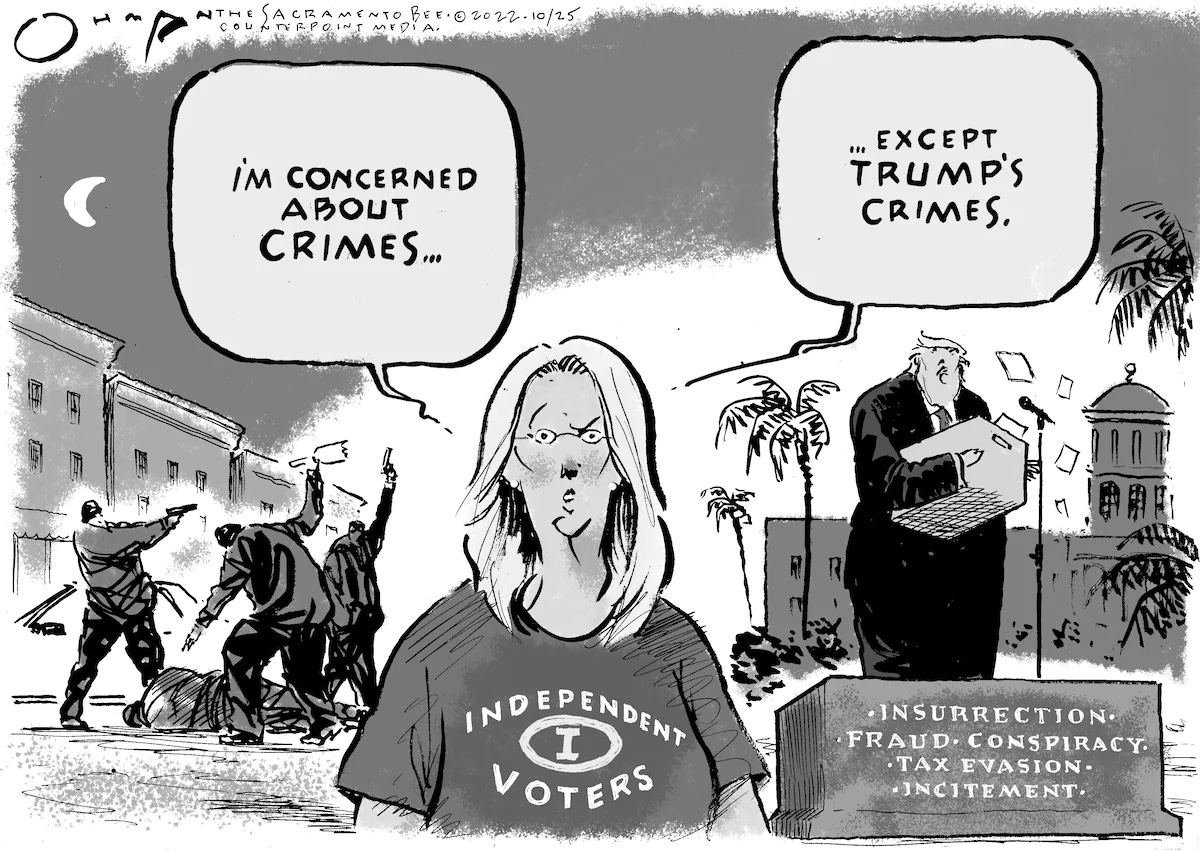

Just two days until voting ends and, thankfully, the attack ads also fade for awhile, although GOP lies and misinformation will probably endure, even accelerate in post-election claims of fraud and miscounts. And now the scent of Musk also intrudes. Setting the stage, I have posted here previously about my latest film that has aired on hundreds of PBS stations in the past month (and still going strong in November), The First Attack Ads: Hollywood vs. Upton Sinclair. But also below my new piece on how the plot to destroy socialist Sinclair and his massive End Poverty in California movement basically brought to the fore all of the leading elements of the (much-maligned) modern political campaign. It includes link to watch it now at PBS.org. Of course, I first wrote about this years ago in my now “classic” book, The Campaign of the Century, feel free to purchase it. Before that, a few cartoons. Enjoy, then subscribe, it’s still free. First, my almost favorite song. Woody, Jeff Tweedy, Wilco, Jason Isbell.

An EPIC Race

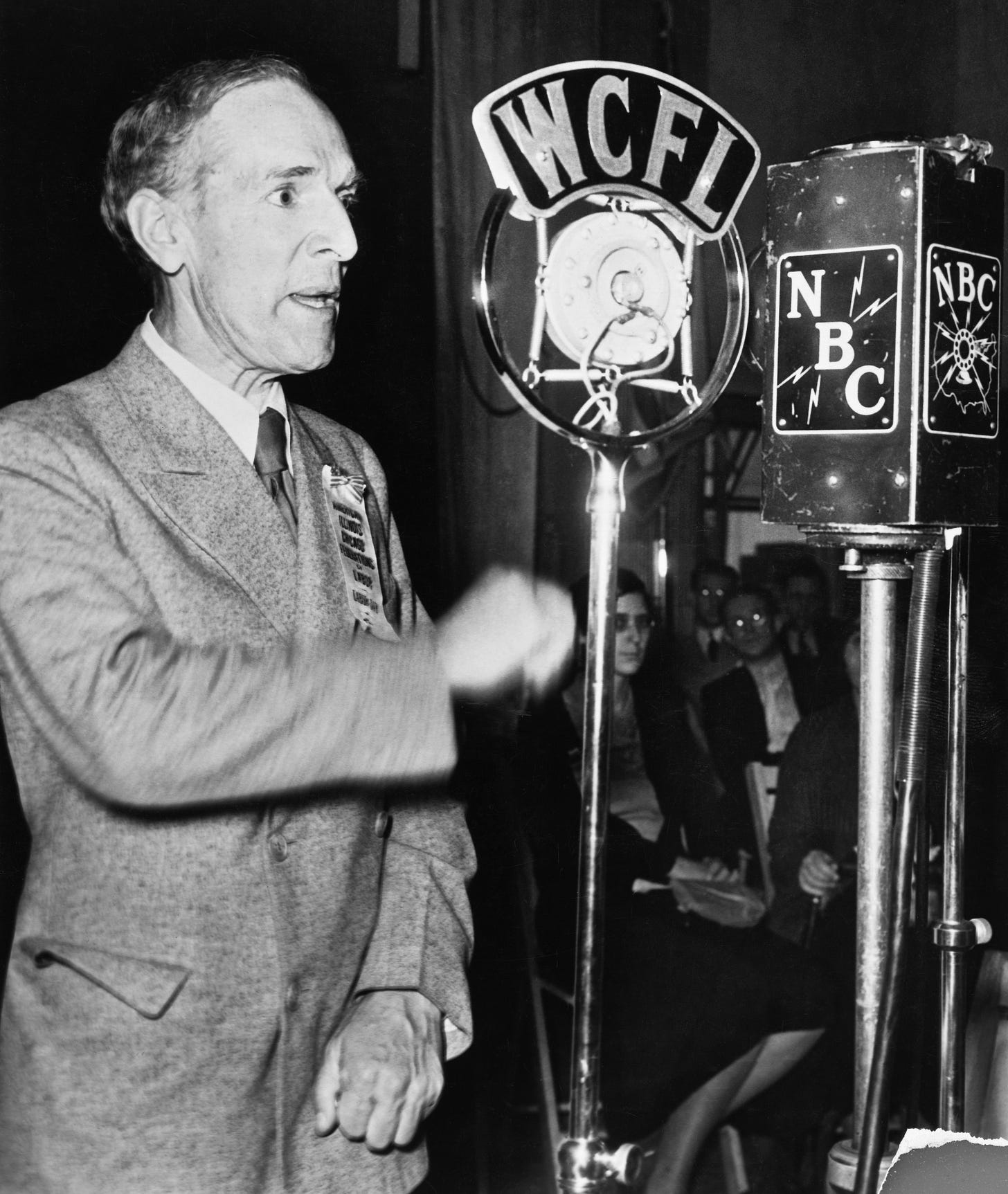

Upton Sinclair, best known as the muckraking author of The Jungle and other polemical novels and broadsides a century ago, is enjoying a revival. His wild campaign for governor of California in 1934 leading an End Poverty crusade served as an important plot point in David Fincher’s recent movie Mank. And it’s hard to spend much time on left-liberal social media these days without confronting his previously little-known aphorism: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."

As a mad rush to another Election Day continues this autumn, however, we should also remember him as the man who inspired the birth of the modern political campaign.

The frantic drive to defeat Sinclair in California set the stage for "spin doctors," advertising wizards, and campaign managers outside the two political parties to take over major campaigns, along with a focus on national fundraising for state races. Hollywood took its first all-out plunge into politics, highlighted by MGM’s Irving Thalberg producing the first “attack ads” for the screen.

This showdown in the Sunshine State, in short, pointed the way from the smoke-filled room to Madison Avenue and to war rooms in Washington, D.C.--from the party boss to the “political consultant.” The anti-Sinclair campaign marked a stunning turning point, “in which advertising men now believed they could sell or destroy political candidates as they sold one brand of soap and defamed its competitor,” Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. later observed. In another 20 years, these techniques would spread east, “achieve a new refinement,” Schlesinger added, “and begin to dominate the politics of the nation.”

It's why I called my book about the race The Campaign of the Century. Now my film The First Attack Ads: Hollywood vs. Upton Sinclair is airing via PBS stations and apps across the country through Election Day and already online for everyone to watch, produced by old friend and colleague (and Oscar-nominee) Lyn Goldfarb.

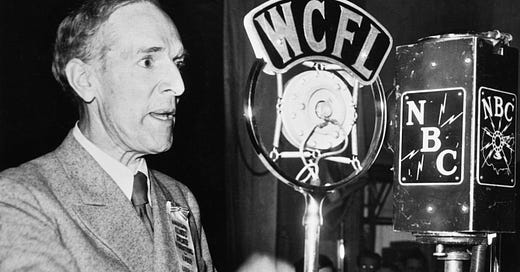

After changing his party registration from Socialist to Democrat, Sinclair inspired one of the greatest mass movements in U.S. history, known as EPIC (for End Poverty in California), calling for radical change even while embracing FDR and his New Deal. Still, political insiders and pundits were shocked when “Uppie” swept the Democratic primary for governor that August. His GOP opponent would be incumbent Frank Merriam—"a hack politician of the hollowest sort,” mocked H.L. Mencken—so Sinclair was viewed as the frontrunner.

Naturally, all hell broke loose. Political analysts declared that this marked the high tide of electoral radicalism in our country. Movie moguls threatened to move back east if Sinclair took office, an effective bluff. The Los Angeles Times slammed Sinclair’s “maggot-like horde” of supporters; the Hearst press throughout the state was little kinder. State GOP leader Earl Warren, the Alameda County district attorney, joined by conservative Democrats, warned of a Communist threat.

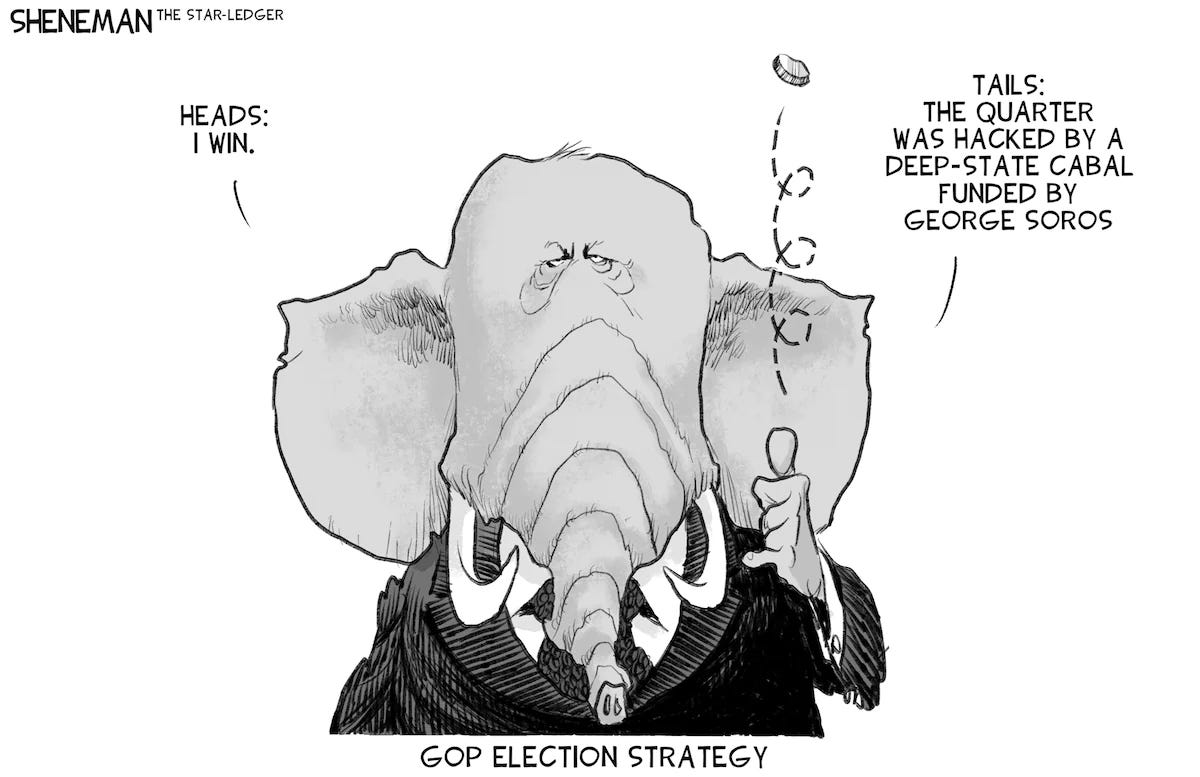

The likelihood of a former socialist governing the nation’s fastest growing state sparked nothing less than a revolution in American politics. Freelance experts, hired by the GOP or by hastily-formed front groups such as United for California, made unprecedented use of direct mail, radio and opinion polls. Millions of dollars for the anti-Sinclair slush fund poured in from across the land. One of the nation's leading advertising firms, Lord & Thomas, under the legendary Albert Lasker, created red-baiting materials. A young staffer from the white shoe law firm Debevoise & Plimpton in Manhattan played a key role.

The Northern California duo of Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter--later recognized as the nation's first "political consultants"--helped devise one of the most extensive smear campaigns ever. Profiling the pair, whose outfit was named Campaigns Inc., Carey McWilliams would call this "a new era in American politics—government by public relations."

Most of the Hollywood moguls docked employees a day’s pay to aid Merriam. Few resisted (among them, James Cagney and, maybe, Katharine Hepburn). The political innovation that produced perhaps the strongest impact was the manipulation of moving pictures, as MGM’s Thalberg produced three faked movie shorts for the screen (precursor of modern attack ads). Sinclair’s lead evaporated and Merriam won re-election by over 200,000 votes.

What was the legacy of the Sinclair campaign? Several EPIC-backed candidates were elected to the state legislature, including future congressman Augustus Hawkins. FDR embraced the general spirit of some of Sinclair's proposals, bolstering his push for a Social Security system and Works Progress Administration. Outrage over the studios' actions in 1934 sparked support for the new Screen Writers and Screen Actors guilds, and from this emerged the "liberal Hollywood" entrenched today. In 1938, EPIC activists helped elect the state's first Democratic governor, Culbert Olson, and the state party has tilted to the left ever since.

Led by the example of Whitaker & Baxter, political consultants began taking over national and state campaigns, and increasingly drew on advertising, direct mail, publicity, and fundraising experts. Clever television spots arrived with the Eisenhower vs. Stevenson race in 1952 and attack ads (from LBJ’s 1964 “daisy” commercial to 1988’s “Willie Horton” example) soon began to dominate. All of this, as longtime Democratic campaign strategist Paul Begala recently noted, was “presaged” by the 1934 innovations in California. When Jill Lepore wrote a feature on Whitaker & Baxter for The New Yorker ten years ago, the headline read: “The Lie Factory: How Politics Became a Business.” The lies and the business of politics only seem to accelerate today