Exclusive Excerpt from My New Book

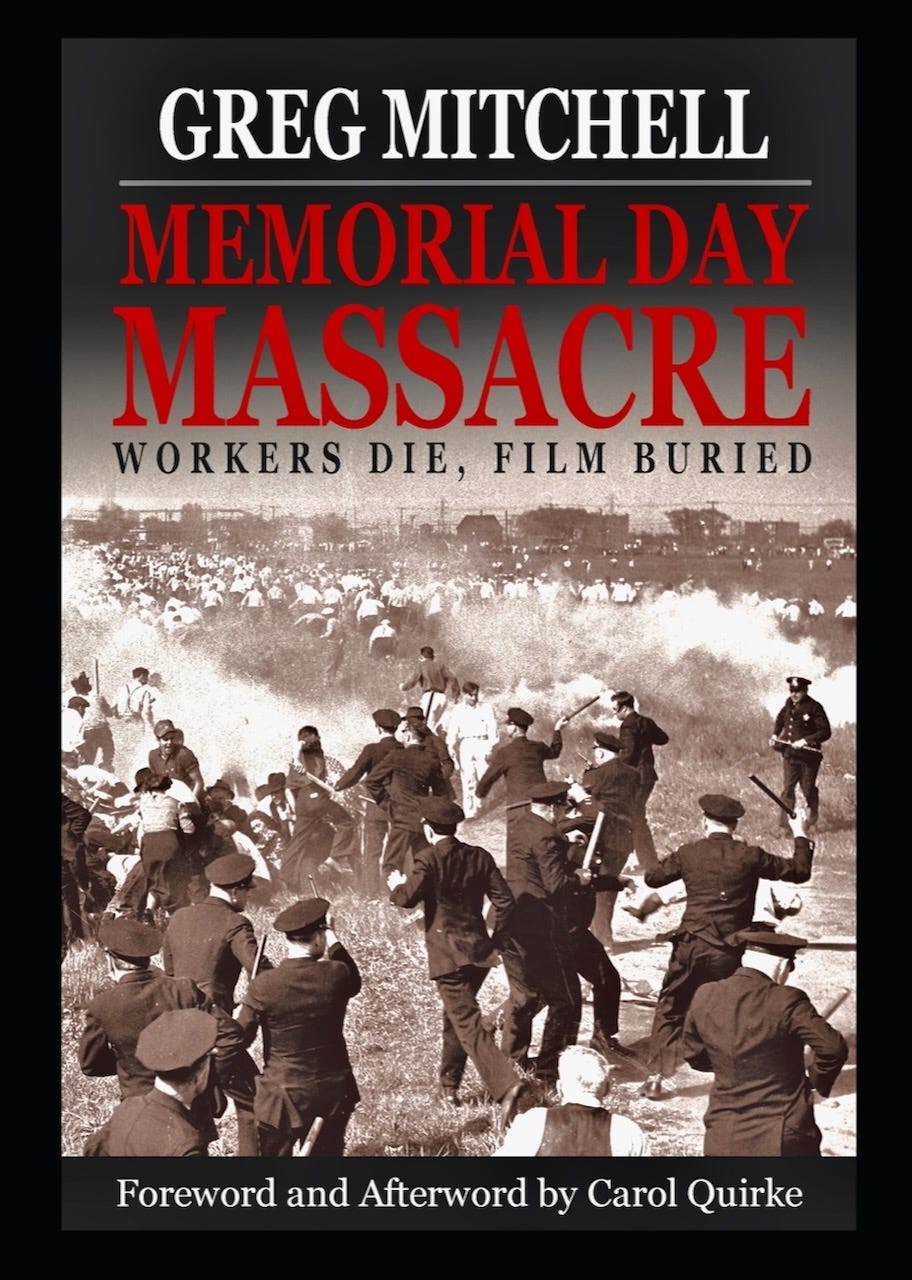

A companion to my new PBS film, "The Memorial Day Massacre," the first oral history exploring the murder of 10 workers in Chicago.

As I have posted here previously, my new film for PBS (and second for them since last autumn), Memorial Day Massacre: Workers Die, Film Buried, premiered over KCET in L.A. last weekend and is now rolling out around the country. But, crucially, it is also now available for everyone everywhere to view (at 27 minutes) for no charge via the film’s main site, which includes background and praise from numerous notables, or very easily via PBS.org and PBS apps. It’s produced by Lyn Goldfarb and narrated by Josh Charles.

There’s also a companion book with the same title, just published, the first oral history of the tragedy. The book (my 13th), in both paperback and as an e-book, features eyewitness accounts by numerous activists and the wounded, and compelling and unique reflections by the likes of Gore Vidal, Studs Terkel, Howard Zinn, Howard Fast, and Dorothy Day, even a cameo by Ayn Rand. Read more about the film and book including praise from notables here. My L.A. Times op-ed here.

In a nutshell: As the Depression continued in May of 1937, steel workers at massive plants in the Midwest and Pennsylvania sought recognition for their new union and basic concessions such as, gosh, the eight-hour day. Police in Chicago clubbed picketers near Republic Steel so union organizers called for a holiday picnic to build support on the wide prairie not far from the plant. The festive occasion drew a crowd of maybe 1500, including many women and children dressed in their Sunday best. The organizers then called for a ragged protest march to the plant.

A contingent of a couple of hundred police halted them halfway there. Soon, forty marchers would be shot, most of them in the back or side, and ten would be dead or dying. Another fifty, clubbed by the cops, suffered head wounds. It was all captured on film by a Paramount News cameraman, whose shocking footage would then be suppressed—until leaked to a famed reporter and then a crusading U.S. Senator screened it at a sensational D.C. hearing.

Here, below, from the book, are a few of the eyewitness accounts of the massacre. (Studs Terkel would not arrive at the site until the next day, you read how he got involved here.) See also excerpt from foreword for the book by Carol Quirke—on her uncle getting shot that day.

Again, the book is available at both Amazon and Barnes & Noble for about $12 for the paperback and $7 for the e-book.

Shots Fired!

MEYER LEVIN, author of Compulsion and other bestsellers: Violence was so well anticipated that on the morning of Memorial Day swarms of press photographers and newsreel trucks were on the scene to record the clash. As the morning progressed, more and more tales of the ugly temper of the police drifted to the strike headquarters, and finally as the march was being formed there came definite warnings, “They’ll shoot.”

SAM EVETT, union activist: I got there early before the speeches and walked down by myself across the open field toward the plant. I watched the Paramount News fellows set up their newsreel cameras on the truck. And I listened to some of the police talking to themselves, saying, “Let those bastards, the marchers, come down here and we'll take care of them when they come down.” You could sense they were going to do their damnedest to give the pickets hell, and it was also a reaction to the Friday night incidents. They had been quartered inside the gates at Republic Steel, in the cafeteria, and records show they had been furnished clubs by the company, and also tear gas.

HOWARD FAST, author of Spartacus and many other novels: It was a serious occasion, but somehow something in the day, the holiday, the sunshine and the warm summer weather made the festive air persist. Vendors wheeled wagons of cold pop and brick ice cream was to be had at a nickel a cake. For the young folks it was the first strike—they sat under the trees with the girls, grinning at the way the strike committee worked, and poured sweat.

MOLLIE WEST, labor activist: By the time we got there it was a sea of people, and the most interesting and wonderful thing was that it was a family day. People came out there like: “We’re going to support the steel workers and we’re going to enjoy a picnic day with our families.” And it looked like God shone on that idea. There were a number of speakers, and then they suggested that we all walk towards the plant gate, to show that since they refused to allow picketing right in front of the gate this would be a nice way of walking closer to the plant.

CAPT. JAMES MOONEY, supervisor in charge of police that day: I called Capt. Kilroy and the platoon commanders, and I told them I expected a march on the plant and I expected every man to do his duty and hold that line—the marchers were not going to go into that plant. I told the lieutenants they were responsible for every man in the platoon. I told Capt. Kilroy we expected trouble in getting them to turn back. I said, “I don’t want anybody hurt, we will try to talk to them. Maybe we can turn them around, but I want everybody to hold their head, not use revolvers unless they have to.” They all carried the regulation revolver, a Smith & Wesson or a Colt, four-inch barrel.

MEYER LEVIN, novelist and Esquire editor: Soon the flag bearing head of the procession moved across the scraggly industrial wasteland toward the plant. We fell in alongside. There is courage in a march of this kind, different from war. In this kind of civil strife, people walk, without arms, into contact with a line of armed men standing directly before them. We had put ourselves in this, and now we knew what it was. Were we only well-meaning meddlers, or was it possible for citizens to act effectively in a struggle of this kind?

HAROLD ROSSMAN, newspaper reporter: As I came to the location I noticed something that was very strange, because in a short block, just on the other side of the empty lot with houses, there was a very large contingent of uniformed police standing there. They were carefully hidden so that the people who were trying to walk across the prairie could see only a few cops there, they didn't realize there was this huge police presence. It was obvious when I saw what was happening that a trap had been set for these people.

I noticed that there was a real tension there and my attention was caught particularly by one particular black officer. He kept pulling his gun out and putting it back in its holster, and pulling it out and putting it back. There was nothing happening that justified that, and yet obviously he had some sense that he wanted to have his hand on his gun.

LUPE GALLARDO MARSHALL, social worker, Hull House volunteer: I was with a young writer who, like myself, was from Mexico, and had invited me to come with him. I was right near the front near one man carrying the American flag. The police started cursing us. The one directly in front of me yelled, “What the hell are you bitches doing out here?” A police officer named Higgins called me a vile name.

The police were closing ranks, crowding us, pushing us back all the time, and I said to one of the officers in front of me, “There are enough of you men to march alongside these people and see that order is kept.” And he answered me, “Like hell! Like hell there are!” There was an officer in front of me who had his gun out.

PHILIP IGOE, patrolman: We could see Capt. Mooney with his hands up in the air pleading with them to go back. The foremost ones in the first ranks seemed to be typical agitators that I have encountered a good many times. I would say that a good many of them were under the influence of marijuana cigarettes. They develop certain idiosyncrasies that are pronounced. The eyeballs are red, there is a facial grimace, at times they break out in hilarious laughter while they are kind of frenzied like. A good many seemed to be under the influence of liquor in cooperation with that. Some of them made a monotonous chant, “CIO, CIO.”

ORLANDO LIPPERT, Paramount News: The marchers were at the police line. I made a few scenes of the two lines closely together and also made some close-up shots of demonstrators and policemen talking together. I changed lens and made two or three closer shots of the police and the demonstrators talking. Then I changed lens again as the combat broke out. A small group of demonstrators, I would say roughly 20 of them or so, were pushed by those in the rear of them into the police line. This apparently was the fuse that ignited the situation out there.

RALPH BECK, newspaper reporter: From my right, about 20 feet back, someone threw a branch over the heads of the strikers in the direction of the police. About eight police to my right in the front shouted “watch out,” and the next thing I heard was a shot from the rear of me, about 15 feet roughly, from the spot where the branch may have landed. I turned around and saw a policeman’s revolver pointing in the air. A large number of policemen around me and to my rear drew their guns and fired—those in the rear firing into the air, and a few on the frontline firing point blank into the crowd. There was a total volley of about 200 shots. The mob broke and ran. The police put their revolvers back in their holsters, those who had them out, and started to work with their clubs. None of the marchers were fighting back, they were just trying to protect themselves. They were not trying to injure the policemen m any way, they were just trying to get away for their own safety.

MOLLIE WEST: All of a sudden we heard shots. We didn’t realize what was happening, and then pretty soon we found that the line instead of going forward was running back because people began to realize they were being shot at, and they were trying to move out of the line of fire. I was knocked down. I lost my glasses. A whole number of people were piled up on top of me, and I could barely breathe. I don’t know how long the shooting took place, but also there was tear gas, and the tear gas blinded some of us, and we began to inhale it and it began to choke some of us.

When the shooting finally stopped and silence prevailed, people finally began to get on their feet, and when I finally stood up, in total bewilderment, I looked around, and I saw a battlefield.

JESSE REESE, union organizer: I’d never seen police beat women, not white women. I thought, “I’m here with nothing, I should have brought my gun!”

LOUIS CALVANO, steel worker: I was marching between the two flags in the front line. When we reached the police, one opposite me said he had orders to keep us away and we’d have to get the hell back. Then he yelled, “Duck!” and he hit me on the head. I turned and tried to run. A black fellow whom I since learned was Lee Tisdale took hold of me and helped me get away as I was dizzy and wasn’t sure of my direction. I had gone just a few feet when a bullet grazed my left cheek. Just before this, Lee Tisdale had left me. I do not know if he was clubbed or shot then or not, but he later died.

GEORGE HIGGINS, patrolman: I waited for my chance and measured him off and, sock, I smacked him. Officer Oakes then got up and shot this Rothmund, who was identified at the morgue. Oakes shot him again and perforated him in the stomach. This was the lousy Communist….I’ve been in that race riot [of 1919], I’ve been in that stockyards strike with all the foreign savages, but this beats them all.

ADA LERER, Women’s Auxiliary of the CIO: I was with a group of girls singing “Solidarity Forever.” I was in the middle of the parade toward the righthand side and I noticed people were running, falling down to the ground. I heard some shots. I didn’t want to fall down because I am five months pregnant. Then I got hit across the buttocks and I realized that if I did not throw myself on the ground I would be badly hurt.

MEYER LEVIN, novelist: I ran a little distance when I heard a child say, “Pa, I am shot,” and I saw the child a few feet behind me. He seemed to stumble, let out a wail and began to hop. He was shot in the foot. A man picked the child up and began to run with him. I ran almost parallel to them for about 30 or 40 feet. I thought at that time that the man who was carrying the child was his father, but I found out later that he was not. This man became exhausted, so I took the child, who was about ten, from him and carried him, running toward Sam’s Place for quite a distance. I then saw a car with a Red Cross sign on it going toward Sam’s Place and I went to it. I tried to put the child in, but it was full of wounded and there was no room, so I continued to carry the boy until I was exhausted, and then two other men took him from me.

REV. CHESTER FISK: By that time the police on the left side had come up. I was still standing there with my camera under my arm, I had finished taking these pictures of them beating the chap on the ground, and two young policemen came up to me and apparently realized I was not a demonstrator and so spoke to me rather casually. We discussed the tear gas and how terrible the whole incident had been, and after both of those men went away a third policeman came up to me, a rather older gentleman, who still had his gun out in his hand, and he said, “What the hell are you doing here?”

I said, “I am a preacher. I was asked to come down here as an impartial observer.” He said, “Well, this is a hell of a place for a preacher be.” I made the comment that I thought perhaps it was a good place for a preacher to be. He said, “Well, get the hell out of here.”

MEYER LEVIN, novelist: I reached Sam’s Place and went into the building and saw several people lying on the floor face down, bleeding, with their clothes torn, a number of people on cots, more than one person to a cot, who had bullet wounds, and a great many people who were bleeding from the skull and down the face. The best that our friend, Dr. Larry Jacques, could do was to examine them as they were brought in, and to see that the serious cases got taken first to the hospitals. I stumbled around trying to help him, gathering volunteers to move the wounded, some of whom lay doubled with their hands to their bellies. I began to help carry people into cars that were taking them to hospitals. I carried three or four people who had bullet wounds, put them in the car.

LUPE MARSHALL, social worker: They started bringing the wounded in by their feet and their hands, half dragging them and half picking them up. They piled them one on top of the other. There were some men who had their heads underneath others. Some had their arms all twisted up, and their legs twisted up, until they filled the wagon. And there was one man, a blonde fellow. They grabbed him and shoved him in the wagon and I noticed that he had two red stains about the size of a penny, one on the upper side of his abdomen and one lower. None of the men that were in the wagon with me were able to sit up. None of them sat on the benches. I had to lift my feet up on to the bench to allow them to put the men in there.

I started helping these men, straightening out their heads and lifting their arms from underneath. I noticed that there was one particular fellow who looked very haggard. There was a heavy-set man that had fallen on top of him and this fellow was pinned completely. I straightened him out, and managed to get his head on my lap. I noticed his face was getting cold and was turning black. He was motioning to his shirt pocket. He had a package of cigarettes there, and I understood he wanted me to light a cigarette for him.

When I did get the cigarette it was caked with blood. So he said, “Never mind, carry on—you’re a good kid.” And he started to mumble “oh, my mother” but he didn’t finish, and he stiffened up. I became somewhat hysterical. Angry, I told the patrolman in the back of the wagon, “l hope you get a medal for this.” I said, “Your children and your wife must be very proud of you.” And he said, “l didn’t do that, I wouldn’t do that, and I have to see that you get medical care now.” And I noticed the tears rolling down from his eyes.