It Was 51 Years Ago Today: With Springsteen in Sing Sing Prison

When we, and then the world, discovered the future Boss.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” “Atomic Cover-up,” and the recent award-winning “The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” He has directed three documentary films since 2021 for PBS (including “Atomic Cover-up”) . You can subscribe to this newsletter for free.

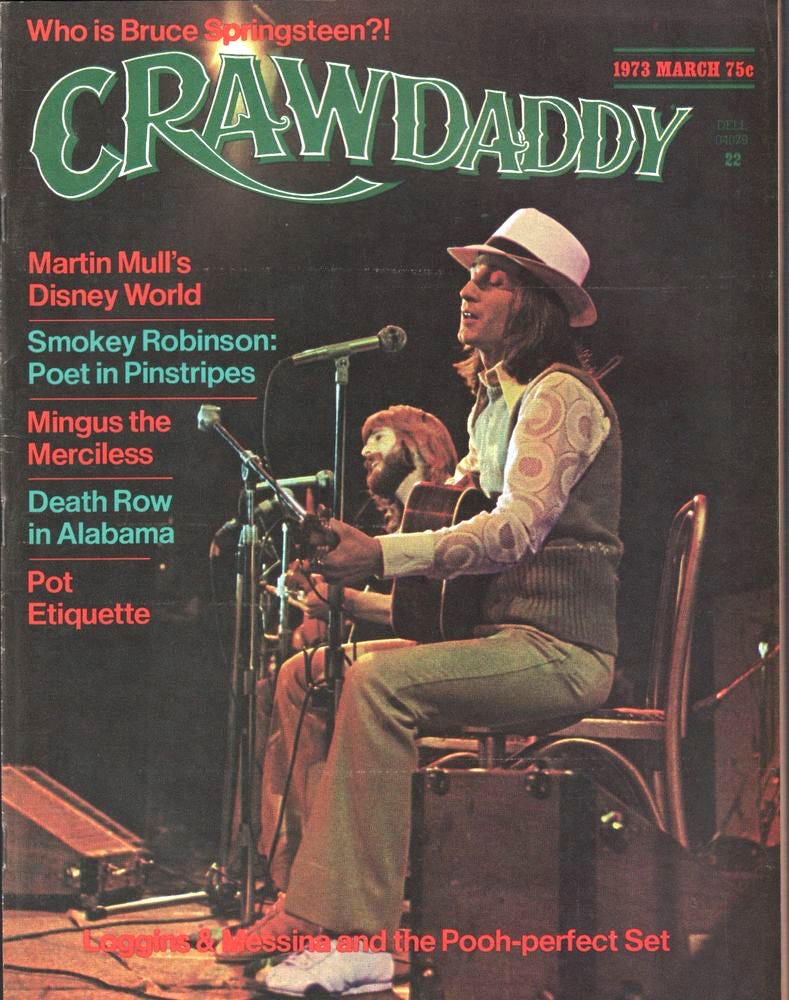

December 7, 1972: Pearl Harbor Day and my birthday. The kid from New Jersey was virtually unknown outside certain areas of Jersey, before his debut Greetings from Asbury Park. His manager tried to organize a major press event, and only Crawdaddy—that is, Peter Knobler and myself—bit. No photos or setlist exist, even to this day…but here’s my account, which I re-post annually. We published the first major piece ever about Bruce and three years later the first cover story. If you don’t have the time, you will find just below my four-minute film short summary which includes a couple of early live Bruce tunes… Enjoy, then subscribe—it’s still free!

At Crawdaddy in the early 1970s, Peter Knobler and I were the two top editors, best friends, and Dylan fanatics, always on the lookout for the “the next big thing” in rock ‘n roll, preferably in the mold of electric Bob. The real Dylan, meanwhile, was still foundering (pre-Blood in the Tracks). Singer-songwriters ruled: Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Cat Stevens, James Taylor, Carole King, Jackson Browne, Elton John, and the like. In late-summer 1972, an item in Billboard caught my eye. Columbia Records talent scout John Hammond—who had signed or discovered everyone from Billie Holiday to Aretha Franklin and Leonard Cohen—had just inked a solo act from New Jersey. The kid was on his own, a complete unknown, but at least the “new Dylan” tag came with a little less cynicism since Hammond had found the original.

Months passed. Preparing my monthly “works-in-progress” box for Crawdaddy in our Manhattan office, I wrote for an upcoming issue: “Solo Jorma Kaukonen….James Taylor’s One Man Dog….debut album of the heralded Bruce Springstein….” Hey, if he was a Dylan clone signed by John Hammond he had to be Jewish, right?

A few days later, in early December 1972, I got a phone call from a brash, fast-talking fellow who claimed to be Bruce’s manager. His name was Mike Appel, and even before his client’s first big gig or album he was anointing him the hottest act of the decade. He wasn’t afraid to drop the name of Dylan—plus Keats, Byron, Elvis and, maybe, Shakespeare. He also had a bridge he wanted to sell me. On the other hand: I was probably one of the few people in the biz who knew who this kid was (and recalled the Hammond connection). So I kept listening as he blew hard in my ear.

What was this hypester offering? Press party? Test pressing? Payola? Well, no. It seemed that Bruce was no longer a solo act. He now had a band and they were about to perform their first show, a publicity event disguised as a do-gooder: behind the walls of fabled Sing Sing Prison up in Ossining, N.Y. (a village later known as the home of Don Draper). Sort of an East Coast version of Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison, minus a star at the center. Well, I’d always wanted to see the inside of a max security prison—as a guest—and the gig was set for two days later, on my 25th birthday. So I said yes.

Then I mentioned it to Knobler, who was editor-in-chief, and he also wanted in. Peter had quite different Sing Sing associations from his early childhood--the Union Square protests surrounding the Ethel and Julius Rosenberg case. The accused “atomic spies” were held at Sing Sing and eventually executed in the electric chair. Maybe we’d at least get a look at Old Sparky while we were waiting for this unlikely Springsteen showcase in the Big House.

___

Early in the morning on December 7, Peter and I met at Appel’s office in midtown. Mike’s song publishing arm, with a partner named Jim Cretecos plus help from (later well-known author) Bob Spitz, was called Laurel Canyon Ltd. Their claim to fame: Writing the million seller for the Partridge Family, “Doesn’t Somebody Want to Be Wanted.” Now they had Bruce’s songwriting rights, whatever that was worth. Mike turned out to be an engaging dark-haired guy in his late-20s with a military helmet on his desk—he was an ex-Marine. He started telling us about how he met Bruce gigging around Asbury Park in a bar band the previous year and encouraged him to write, not just play.

His mouth went nonstop so I could well understand how John Hammond, a few months back, might have agreed to audition Bruce just to silence his manager. But Hammond, Mike said, had only visualized (and heard) Bruce as a singer-songwriter type and was not happy to learn he had employed a full rock ‘n roll band. The drummer’s nickname was “Mad Dog”! This did not bode well. It was almost as if Dylan had arrived in his Woody Guthrie mode and turned around and hired The Hawks in the space of a few months, not a few years.

Minutes later, in the rain, Mike led us to a van parked under the West Side Highway, where we met Bruce and some of the band. Bruce was endearingly scruffy, with a fuzzy, Dylanesque half-beard, short curly hair, a big jaw and dressed in a hooded grey sweatshirt—not exactly rock star attire, though perhaps safe for Sing Sing. There was a big black guy named Clarence and a thin, bearded kid, Garry, but who knew what instruments they played. Another vehicle was carrying their axes and the rest of the band north as we settled in the back of the van, feeling more like roadies than journos.

It turned out that Mike had asked dozens of other reporters or editors from local newspapers and national magazines to make this trip--and all declined. The fact that this was just a little over a year after the massacre at Attica prison might have scared off some of them. Or the music press heard whispers that Bruce was being referred to by some inside Columbia as “Hammond’s Folly.” In any case, the band members were clearly thrilled that a couple of guys from legendary Crawdaddy—launched in 1966 before Jann Wenner got the idea for Rolling Stone—had taken Appel’s dare. I don’t recall the conversation on the way up, just that “Brucie,” as he seemed to be known, displayed an infectious, easy laugh and a sense of wonderment and doubt. That made three of us.

The stony prison, we found on arrival, squats along the Hudson River in an oddly lovely setting, offset by barbed wire and guard towers. It was still raining. (Ten riders were approaching, the wind began to howl.) It was founded here in 1825 and looked every painful day of it. Inside, we were frisked and guided through metal detectors. After our hosts took a careful head count, we walked past offices, then cells, but swiftly, urged to avoid eye contact with any cons, as we were escorted to the setting for the lunch time concert—the historic, high-ceilinged, auditorium-sized prison chapel.

It had a decent-sized stage and the equipment was already being set up by Bruce’s crew and a sound man named Tinker—we were told Brucie once lived with him in a “surfboard factory” near the Jersey shore. Or something like that. They were assisted by a few cons, who had gained extra privileges due to good behavior (we hoped). We were already running a little late. Thank god Brucie had at least one imposing black guy in the band many of these guys—at least the ones who weren’t racists or neo-Nazis—could relate to. Indeed, a couple of them joked around with Clarence Clemons, who was holding a major saxophone. (He might have to use it to defend himself if a riot broke out near Cell Block #9.) Bruce huddled in his grey hoodie, a little nervous, but I didn’t know if it was the audience—they gave new meaning to the expression “a tough crowd”—the setting or just wondering what to play. Dylan, at least, would have had “I Shall Be Released” in his pocket, and “Percy’s Song.”

Finally the doors opened and a few hundred residents came in, probably straight from lunch so at least they weren’t hungry. Once they settled in, someone introduced the band but I can’t recall if it was the chaplain, warden, or head of the Prisoners Liaison Committee. Then Bruce and band began their first tune, a fast number.

Damned if I could make out a single word, standing in the back of the stage behind the equipment, as the syllables flew by in bunches. I was told that it was a Bruce original. The crowd greeted it tepidly. Bruce tried another in that vein, and inspired even weaker response. (At least no one shouted, “Judas!”) It was hard to tell if it was the material or just the sound system that sucked. Bruce’s eyes showed quiet desperation as he glanced at band members, seeking verbal or musical advice. Now Clarence stepped in, whispered something to Bruce, then shouted the opening of Buddy Miles’ classic soul rocker, “Them Changes.”

Oh my mind is going through them changes.

Looks like I’ve committed a crime

Perfect. The crowd went wild as Clarence, clearly no singer, wailed. Bruce cracked guitar lines and Clarence blared away on his huge horn. The song went on, and on—the band maybe too scared to switch to something else. Suddenly, a compact, heavily muscled, middle-aged black man started running down an aisle toward the stage. Was he about to pull out a shiv and stab the smallish white boy standing at the center unprotected except by his Fender guitar? The guards, off to the side, were helpless to intervene. Bruce’s eyes showed surprise, then a bit of terror. So did mine, no doubt. The con jumped on stage, strode toward an open mic, and whipped out ….a tiny alto sax! And started blasting. He was great! For all we knew, the guy used to play with James Brown or Coltrane. (The setting, below, from earlier in the century.)

Now the crowd really erupted. The band, plus one, kept hailing “Them Changes” for another few minutes but finally brought it to a halt, not wishing to press their luck. The alto man decamped. Bruce played another number or two, then must have gotten a signal to wrap it up. He thanked the cons for coming—as if they had bought tickets or had much choice. Then, like a principal addressing a mid-afternoon school assembly, Brucie uttered these immortal lines: “When this is over…you can all go home!” Had to laugh, even if he might have gotten all of us killed.

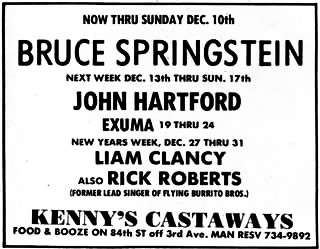

So we still didn’t know what John Hammond saw in Brucie, musically, though we were getting the personal appeal. But at some point during the day we learned that Bruce and band would be playing two sets that night at the tiny Upper East Side folky club Kenny’s Castaways. Naturally we decided to go, as my oddball birthday celebration continued.

We arrived early for the 9 p.m. set to say hello to Bruce and the guys around the bar out front. They were happy to see us, since there were only a dozen or so paying customers in front of the stage, huddled around café tables lit by candles. Bruce finally cleared up one thing: his last name was Dutch, not Jewish, in origin. Even so, the club had spelled it “Springstein” on the sign out front.

We noticed that Brucie was drinking a Coke, not a beer. Earlier someone had told us he eschewed drugs, as well. After witnessing the band in full honk at the prison, we were surprised when Bruce came out alone, with his acoustic guitar, to start the set. This at least gave us a chance to experience what Hammond first heard and thought he signed. Bruce was encased in the same jeans and hooded sweatshirt he’d worn earlier that day. As he was checking the tuning on his guitar, he fumbled a pick, and had to bend over to pick it up. His live act could only take off from here. That he would one day headline a Super Bowl halftime or play for Presidents seemed rather remote.

I can’t recall what the first song might have been—the two sets that night are scrambled in my mind--but it likely was “Mary Queen of Arkansas” or the unrecorded “Song to Orphans,” very slow tunes, heavily strummed with emotional vocals, his eyebrows dancing. “High society vamps/And ex-heavyweight champs/mistaking soot for soil,” he murmured in “Orphans.” Okay for that type of thing, but what else ya got?

Possibly in the second slot was the more exciting ”Lost in the Flood,” soon to show up on the debut album, with Bruce at the piano (he had all the singer/songwriter instruments covered). He had great stage presence, which turned awkward between songs. As if he was at a rehearsal, he advised himself, “Got to get these wires off the keys.” The heavy-chorded song seemed to have a Vietnam vet vibe, as it described a “ragamuffin gunner” who “must be from the fort, the high school girls say,” who ends up wrecking his car in a fiery crash. Tremendous. Did that mean he was somewhat “political,” we hoped?

Then he introduced lank-haired Danny Federici, who had played organ at Sing Sing but now appeared with an accordian. Garry Tallent hoisted a…tuba. Bruce had been all business to this point, no jokes at all, but now he loosened up, mugging a bit as he played “Circus Song,” his humorous take on carnival life (“Jesus, send some good women / to save all your clowns”). Where are these songs coming from? I wondered. In any case, the audience response, beyond our table, was rather restrained. Clearly we were not seeing the future of rock ‘n roll.

Suddenly Bruce exclaimed, with some relief, “Let’s bring up the band!” and out came the rest of the gang, as he strapped on his honey-colored Strat and sang, “Madman drummers bummers and Indians in the summer/ with a teenage diplomat…” Didn’t know it, but it was “Blinded by the Light.” Peter and I glanced at each other—here was the electric Dylan wordplay we’d longed for, although, admittedly, in a more adolescent vein. And the band really cooked.

I don’t know precisely what followed. Might have been two other songs off his first (still unreleased) album, “Growin’ Up” and “Does This Bus Stop on 82nd Street.” Or, back at the piano, “For You.” Then he did “Spirit in the Night,” his best tune so far, with Clarence finally getting to wail on sax, the whole thing evoking Crawdaddy hero Van Morrison. Now we were totally bonkers, and then he topped it with a loud, rock and roll finale, written since the album was finished—either “Bishops Dance” or “Rosalita” or “Thundercrack,” doesn’t matter which--uproarious, with wacky humor to boot. The kid could do it all, even play some mean guitar.

Between sets we congratulated Bruce and band without having to fake enthusiasm for once. Then he blew us away with a second set that didn’t repeat a single song from the first, closing with whatever rocker he didn’t do earlier. As I headed across town and Peter went south, we agreed we’d be back for more the following night.

After that weekend, I discovered that the Sing Sing gig wasn’t quite as unique as I’d thought: Joan Baez with sister Mimi Farina, B.B. King, and young comic Jimmy Walker had performed there just two weeks before, around Thanksgiving, That concert was shot for a possible film. Joan did sing “I Shall be Released” and the audience got pretty damn raucous during B.B.’s set, raising clenched fists and all that. The Village Voice had even covered it, and we learned that the sax man who hijacked the Springsteen stage had done the same thing at the Baez/King show! He had a name, Joe Williams, age 40, originally in the joint for manslaughter.

Maybe that’s where Appel got his bright idea for a press junket. Peter and I, meanwhile, decided that we’d publish a major feature on Springsteen, even though no one in our audience had ever heard of him. Or partly: because no one had heard of him. It would be a very Crawdaddy thing to do: risky, possibly self-destructive. Appel had sent over a couple of test pressings of Greetings from Asbury Park. It was an uneven, but enormously promising, debut.

In preparation we would make a pilgrimage to the Asbury area to catch a band rehearsal—yes, in a garage—-and then chat with Bruce at the second floor apartment he shared with girlfriend Diane. Former Brucie bandmate Steve Van Zandt stopped by. We all piled into our car to catch his blues show billed as “Southside and Steve” at a local dive bar. A few days later, Peter returned with our ace photog Ed Gallucci for a more formal interview in Brucie’s tiny kitchen. He also talked to John Hammond.

Then Peter wrote an unprecedented (for an unknown rock act) 8000-word piece with my assistance, that we headlined with a takeoff on a recent Dustin Hoffman movie, “Who is Bruce Springsteen and Why Are We Saying These Wonderful Things About Him?” We even put Bruce’s name above the logo on our next cover.

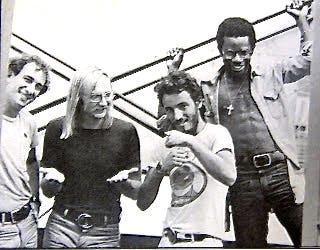

The rest, as they say, is history. For years, as enduring friends and fans, we’d be welcomed backstage everywhere from Santa Monica to Niagara Falls, from Max’s Kansas City to Madison Square Garden and Philharmonic Hall. It was a long way from Sing Sing. (He was Hammond’s Folly no longer.) Bruce even took the stage at the magazine’s 10th anniversary party. Crawdaddy cover stories, penned by Peter, followed in 1975 and 1978. So did a softball doubleheader between the Crawdads and the E Streeters (we swept them). Below: backstage at his Central Park gig, 1974.

Peter and I have gone on to write about twenty-five books between us, but after 1979 never worked together again on a magazine. Funny thing, though, the kid we witnessed fumbling around on stage at Kenny’s did go on to play the Super Bowl and the White House. Them changes, indeed. And when Dylan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, guess who did the honors?

_______

Note, I’ve written a couple of other popular memoir pieces here regarding Bruce: “Running with Bruce, Down Thunder Road” and “When I Rode with Springsteen to MY Hometown.” Around 2008 he would pen a short preface for my book on political and media failures on the Iraq War, So Wrong for So Long.

I've had more than a few rock n roll moments in my life, but nothing like that one. Wonderful.

1234!! Such a fab piece!!!