Leonard Bernstein, Beethoven, and the Berlin Wall

His most famous and enduring concert in his final year marked the fall of the Wall--with the Ninth Symphony and a key word change.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including the bestseller on escapes under the Berlin Wall, “The Tunnels,” “Journeys With Beethoven,” and the recent award-winning “The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” He has directed three documentary films since 2021 for PBS (including “Atomic Cover-up”) . He was #2 editor at the legendary Crawdaddy during the 1970s. You can subscribe to this newsletter for free.

Leonard Bernstein, the renowned conductor, composer and liberal political activist—and subject of the new Bradley Cooper movie Maestro--came to Germany in December 1989 just after the Berlin Wall was cracked open and thousands of East Germans poured through to be united with their German brothers and sisters after 28 years of separation. Bernstein was 71, and in failing health. In 10 months he would die of cancer. "Lenny," as he was called by those who knew him, was a magnetic advocate for the belief that music could transform lives and in the process transform the world.

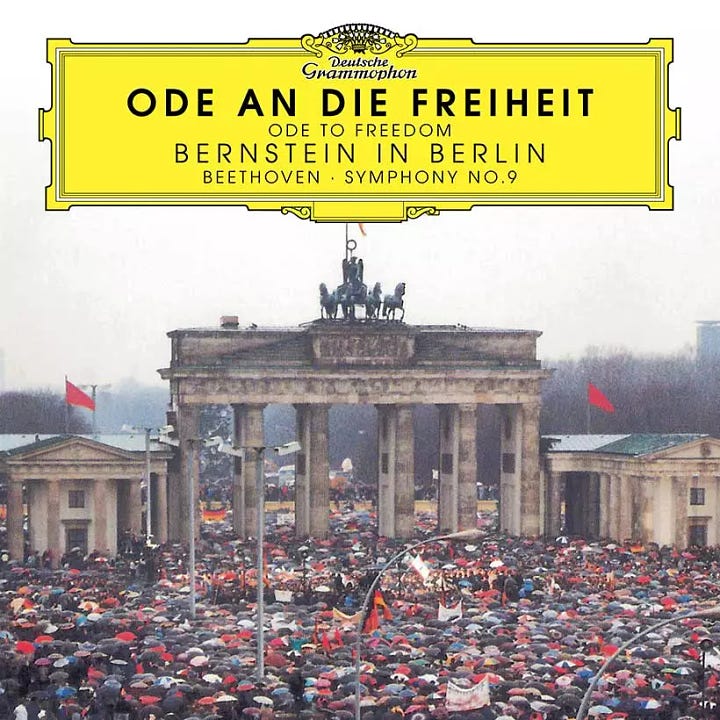

In that Christmas season trip to Berlin, Bernstein would famously conduct two performances of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony with an international orchestra and chorus assembled from the four countries that had just recently shared the city -- the U.S., Russia, England and France. And he would change one word, so that the "Ode to Joy" became the "Ode to Freedom."

You might call it "Revolution With the No. 9."

Kerry Candaele tells the story of the Wall and Bernstein's trip, along with exploring Beethoven's other political/cultural influences in Chile (protesting Pinochet torture), China (in Tiananmen Square), along with a Billy Bragg segment, in his film Following the Ninth, which I co-produced. There's also a book it inspired, which I co-wrote with Candaele, Journeys With Beethoven, with a key chapter on what led to the fall of the Wall and that first celebratory Ninth. It is also mentioned in my recent bestselling book on escapes under the Wall, The Tunnels.

Bernstein's identification with Beethoven was long-lasting, and more than just musical. His social activism for left-wing causes began in his youth, and was consistent throughout his life. His support for organized labor and the civil rights movement, including his notorious (in mainstream media circles, at least) 1970 fundraiser for members of the Black Panthers, and his protests against the Vietnam War earned him an FBI tail and a place on the U.S. State Department blacklist for a time. Leonard Bernstein was at one point put on a list of people to be moved to an internment camp in case of a national political crises.

Tom Wolfe labeled Lenny's political commitments "radical chic," but Bernstein didn't play at politics, as his New Deal idealism existed both before and after his rise to celebrity. In the final decade of his life, he campaigned for nuclear disarmament, for AIDS research funding, for the abolition of world poverty, and for the utopian impulse articulated in Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, that one day "All Men Will Be Brothers" (Alle Menschen werden Bruder).

Bernstein had described his feelings about the Ninth years earlier in one of his television broadcasts that were a hit on American television during the 1950s (he also devoted an entire program to dissecting the Fifth Symphony). Bernstein associated the words of love, peace, brotherhood, joy to the year of his birth, 1918, when an armistice brought the World War I to an end. He added the folk song phrase "ain't gonna study war no more" to the key words that he associated with Beethoven's Ninth. "We are all children of one father," he added, "let us embrace one another, the millions of us."

The Ninth, he rightly insisted, "rang[es] from the mysterious, to the radiant, to the devout, to the ecstatic," but the words of joy and peace are hollow and ineffective when, as Bernstein described the reality of our lives, "we have not yet found ways, short of murder, to act out our suppressed rages, hostilities, xenophobias, provincialisms, mistrust and need for superiority. We still need some kind of lower class as slaves, prisoners, enemies, scapegoats." This impulse embedded in the Ninth, in Bernstein's words, is not a blueprint for a good society that have shown themselves to be tawdry betrayals of our best instincts, when humans have attempted to transform human behavior overnight with a reckless fanaticism. The "crooked timber of humanity" cannot be made straight right here and now. To desire perfection in human beings is to desire the impossible.

But Beethoven, Bernstein believed, represented: "struggle, struggle for peace, for fulfillment of spirit, for serenity and triumphal joy. He achieved it in his music, not only in his triumphal Ninth, but in all his symphonies. And in his quartets, his piano sonatas, and trios and concertos. Somehow it must be possible to learn from his music by hearing it. No, not hearing it, but listening to it, with all our power of attention and concentration. Then, perhaps, we can grow into something worthy of being called the human race."

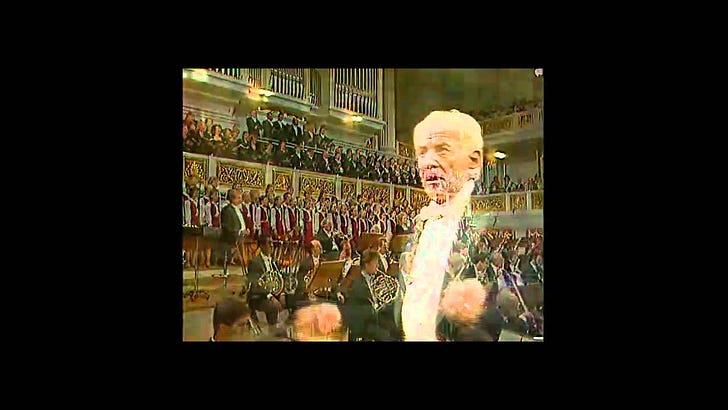

Bernstein brought his history and his sentiments, if not his youthful exuberance, to Germany for two performance of Beethoven's Ninth in December of 1989. The first concert was timed to end at midnight on December 23, when the border dividing the two Berlins would be fully opened for the first time in 28 years. On the second occasion, he conducted the Ninth at East Berlin's Schauspielhaus on Christmas morning. While more than a thousand gathered in the hall, hundreds more stood in the square in front to watch the performance on a giant television monitor. On the live TV broadcast, Bernstein declared, "I am experiencing a historical moment, incomparable with others in my long, long life."

Entire performance with a clip of Lenny in the streets:

Just the finale here:

By then more than 200,000 East Berliners had visited the West for the first time, and about the same number had traveled East. The Associated Press reported, "One West Berliner riding a bicycle and dressed as Santa Claus failed to persuade border guards to let him through ahead of the rest of the crowd."

In keeping with the Ninth's theme of connection across borders, the orchestra included members from the Dresden Statteskapelle and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, as well as from orchestras from the four countries that technically still occupied Berlin -- the New York Philharmonic, the London Symphony Orchestra, the Orchestre de Paris, and the Orchestra of the Kirov Theater, Leningrad. The chorus was made up of singers from both sides of Germany.

Bernstein wrote a friend about the concerts: "I'll be reworking Friedrich's Schiller's text of the 'Ode To Joy' and substituting the word Freiheit (Freedom) for Freude (Joy). Because when the chorus sings Alle Menschen werden Bruder, it will make more sense with Freiheit, won't it?"

He received as much pleasure in conducting the Ninth that day as he gave. Sherry Sylvar, an oboist who played in the concert, said, "When the chorus sang the word Freiheit. ... I shall always remember how his face lit up." In fact, a good part of the world lit up. The concert was broadcast live to more than twenty countries, to over 100 million people, with a recording released on in 1990 as the "Ode To Freedom: Bernstein in Berlin."

The famed conductor had added playful humor to the occasion by imagining that he could make a career of performing the Ninth around the world: "I can't wait to do it in North Korea and China." But he always came back to his first principles when it came to Beethoven: "The dubious cliché about music as the universal language, almost comes true with Beethoven. No composer who has ever lived speaks so directly to so many people, the young and old, educated and ignorant, amateur, professional, sophisticated, naive, and to all these people, of all classes, nationalities, and racial backgrounds, this music speaks a universality of thought, of human brotherhood, freedom, and love...

"In this Ninth Symphony, in the finale, the music goes far beyond the [Schiller's] poem, it gives far greater dimension and vital energy and artistic sparks to these quaint old lines of Schiller. This music succeeds, even with those people for whom organized religion fails. Because it displays a spirit of Godhead and sublimity in the freest and least doctrinaire way. It has a purity and directness of communication that never becomes banal. It's accessible without being ordinary. This is the magic that no amount of talk can explain."

And if there was one person who could explain Beethoven's music in words that all can understand and embrace, it was Leonard Bernstein. He speculated:

"[P]erhaps there was in Beethoven the man, a child inside that never grew up, that to the end of his life remained a creature of grace, innocence and trust, even in his moments of greatest despair. And that innocent spirit speaks to us of hope and future and immortality. And it's for that reason that we love his music now, more than ever before. In this time of world agony, we love his music and we need it. As despairing as we may be, we cannot listen to this Ninth Symphony without emerging from it changed, enriched, encouraged. And to the man who could give to the world so precious a gift as this, no honor could be too great, and no celebration joyful enough. It's almost like celebrating the birthday of music itself.”

My photos of my visit to The Wall Memorial

.

I can't think of a better time for this post, Greg. Until Alle Menschen werden Bruder, we need to read this and listen to your clips, over and over. Thank you, Greg.