Massacres, Then and Now

Final chance to watch "Memorial Day Massacre" film. Plus: Outrage over latest Israeli attack on Gaza refugee sanctuary.

On this holiday Monday: First, if you missed yesterday’s post, here are 15 varied songs marking the day. Next: My “Memorial Day Massacre,” which came out over PBS one year ago, airs today over WTTW in Chicago at 5:30 pm and 10:00 pm, and in many others cities today and the rest of this week. But it has also been streaming over PBS.org and PBS apps for free for quite some time—but that ends this coming Friday. So if you have not watched, here’s your “final” chance for maybe quite awhile. It’s 27 minutes long, and narrated by Josh Charles, with an assist from my old pal Studs Terkel.

As I have written in the past: It explores the murder of ten steel strikers and labor activists (most shot in the back) during a Memorial Day march in Chicago in 1937. And then, how the only film footage of the tragedy was suppressed until a muckraking reporter and crusading U.S. Senator brought it to light. Still, some movie theaters and distributors refused to air the newsreel. And no cops were punished. But it had significant influence, to this day, on labor movements in America.

Read much more here at the film site, plus responses from dozens of notables.

Don’t forget the only oral history, my companion book published last year and available as a paperback and e-book (just $3.99).

Down below, a piece drawn from the book on Studs Terkel’s intimate connection to the 1937 tragedy: He was on the scene the following day.

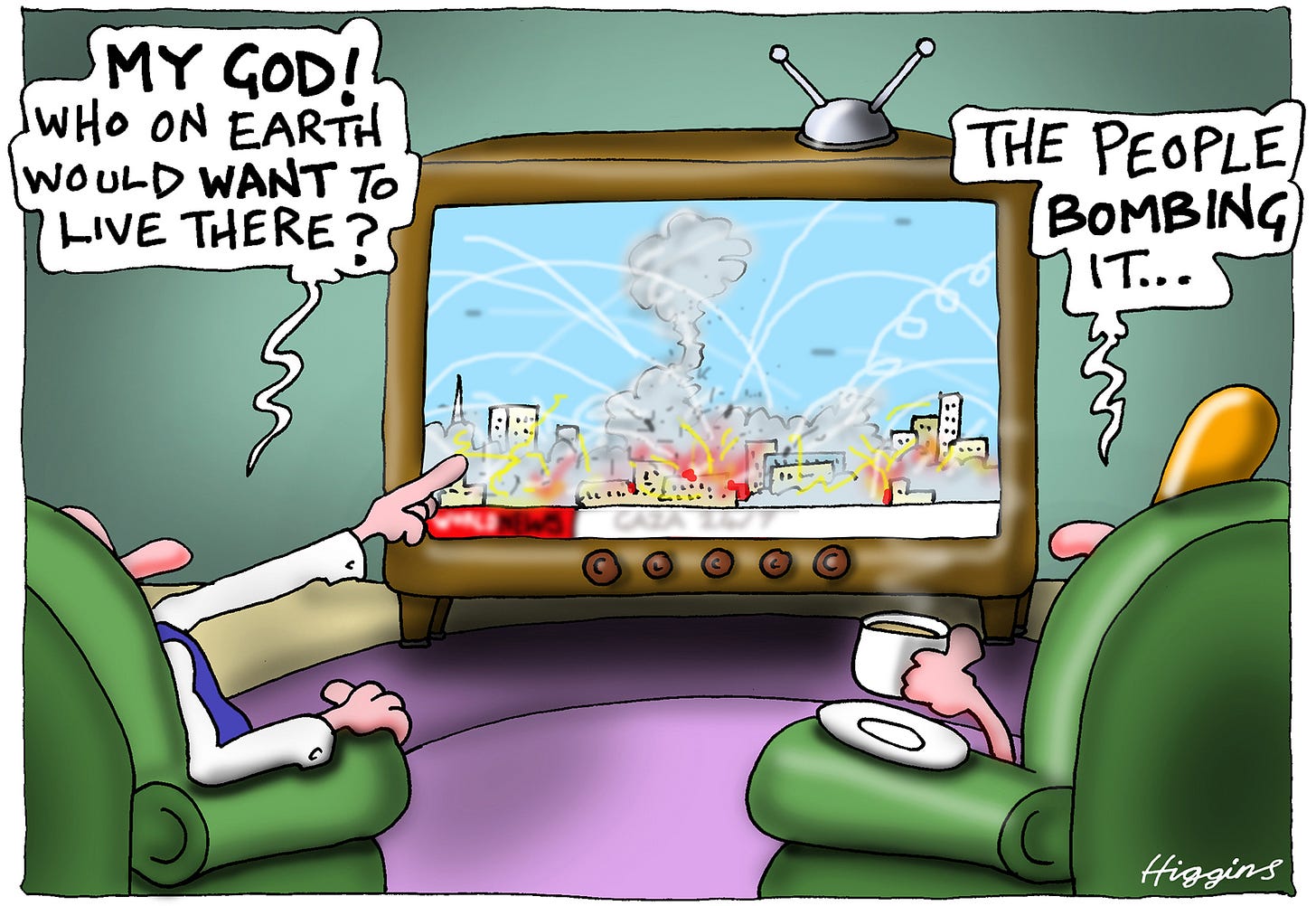

But first, you have probably already read about Israel’s missile attack on another Gaza refugee camp last night with dozens of women and children killed or wounded, sparking international outrage. The images are too horrific to post but here is an illustration or two.

Studs on the Day After: Like the Aftermath of Gettysburg

Studs Terkel, the legendary Chicago radio host, raconteur and author of dozens of books, will probably now become best known to some because one of those books, Working, inspired the new Netflix series of that name from Higher Ground, the production company founded by Barack and Michelle Obama. But I met Studs back in the early 1980s after he wrote a blurb for my first book and then invited me on his radio show in Chicago. We then conversed over the following decades, before his passing in 2008.

Still, I did not know of his intimate connection to one of the most shocking historical incidents in his Chicago until I began research for my new PBS film and companion book, both titled, Memorial Day Massacre: Workers Die, Film Buried. They explore the 1937 tragedy in South Chicago near the old Republic Steel plant when police shot forty strikers and their supporters (hitting most of them in the back or side) and killed ten. The only footage of the incident was suppressed until a famed investigative reporter and a crusading U.S. Senator brought it to light.

Now, nearly 86 years later, Studs provides one of the most significant voices in my film and book, the first oral history on the subject. I’d like to think that Studs—the master of the oral history—would love that.

In 1937, however, he was still a struggling part-time actor. Of course, he was already a political activist. He would reflect on that period: “There were labor battles, historic ones, where the fight for the eight-hour day had begun. It brought the song: ‘Eight hours we’d have for working, eight hours we’d have for play, eight hours for sleeping, in free Ameri-kay.’”

For whatever reason, Studs did not attend the Memorial Day picnic, called by strikers to build support, on the wide Southeast Chicago prairie that led to the massive Republic plant. Organizers suggested that the crowd of 1500 (including many women and children) march toward the distant plant and attempt a mass, legal, picket outside. The ones who tried were stopped halfway there by a contingent of a couple of hundred police. Within minutes, some of the police opened fire with pistols at point blank range and then shot at retreating protesters.

Accounts differ on what set it off. Some of the marchers may have thrown stones and other objects at the police, though hardly at the level that warranted the shootings (and then police waded through the crowd, clubbing many at will). A Paramount News cameraman captured most of this on film.

Studs did make it to the site the following day, to meet strikers and the wounded still being treated at the union’s headquarters nearby, as he recalled: “The day after the massacre, I took a streetcar to the workingman’s bar, Sam’s Place. On this spring afternoon the place is crowded. The men are on strike. Some of them have their arms in slings. Others have bandaged heads. A couple are on crutches. This was a scene out of Matthew Brady’s photos right after Gettysburg. All are in shock. They are among the survivors of a Memorial Day picnic.

“Three of us, members of the Chicago Repertory Group, were called upon…Could we perform at Sam’s Place? Songs, sketches. It would help the morale of the strikers. A guy read a poem. I was an actor in one of the sketches, from Waiting for Lefty.”

Media coverage, both local and nationally (right up to The New York Times), overwhelmingly accepted police accounts of the confrontation—they had to shoot to halt the “mob” who were about to “riot” and invade the plant. Studs would observe: “The Chicago Tribune in those days was headed by sui generis publisher Colonel McCormick, sort of a Colonel Bull Moose figure. He was flailing away at the New Deal daily. One of his former employees called him ‘the finest mind of the 12th century.’ And Colonel McCormick was anti-union, of course. Next to a picture in his paper from Memorial Day of a cop with a club over a fallen worker, was the heading: Worker Attacks Police.”

Paramount, meanwhile, created but then failed to release a newsreel with the footage, claiming they feared it would set off riots in theaters.

A few days after the incident, protesters gathered at the Opera House for a rally. One of the organizers was economist (and later U.S. Senator from Illinois) Paul Douglas. Another was future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg. Among the speakers were poet Carl Sandburg and union leader A. Philip Randolph. The police captain who led his forces on the prairie on the day of the massacre, Capt. James Mooney, came in for particular criticism. Studs attended, and recalls in my book:

“It was the most highly-charged event I’d ever attended. I was sitting in the back of the balcony, next to a steel worker. You couldn’t squeeze anyone else in. You could taste the wrath of the audience. Carl Sandburg, who was a great ham, was up there swaying, taking a year-and-a-half to get a sentence out. The steel worker next to me says, Come on.

“The emcee was a gentle old professor named Robert Morss Lovett, who taught literature at the University of Chicago, and he was beloved. ‘Mooney is a killer, Mooney is a killer,’ he said, ‘and we’ve got to stop these killers!’ It was taken up by the whole audience. It had become a roar for justice. I haven’t the foggiest notion what happened to Capt. Mooney. Was he punished? Rewarded? Instantaneously retired?”

In fact, no patrolman or police officials was punished for what happened that day, even after a U.S. Senate probe found them responsible for the massacre. A coroner’s jury judged all of the murders “justifiable homicide.” But Senate staffers had finally brought the Paramount footage to light (you can watch it here).

Studs, of course, went on to great fame as radio host, author and man about town. One of those featured in his bestselling oral history on the Great Depression, Hard Times, would be the doctor who treated the wounded at the site of the 1937 massacre--and provided the crucial testimony to the Senate about the majority having been shot in the back.

Great work, Greg! Some things never seem to change. Thanks for the history!