My First Rock Festival

Another excerpt from my memoir-in-progress returns to 1970 and the biggest festival debacle ever. Plus Lewis Black and period music from the Allman Brothers and Melanie, and new guy Jason Isbell.

We were not stardust, we were not golden, and we had to get ourselves back, for a shower….Enjoy, then share, comment, subscribe (it’s still free). First, the daily political cartoon.

Me and Melanie Down at the Ski Yard

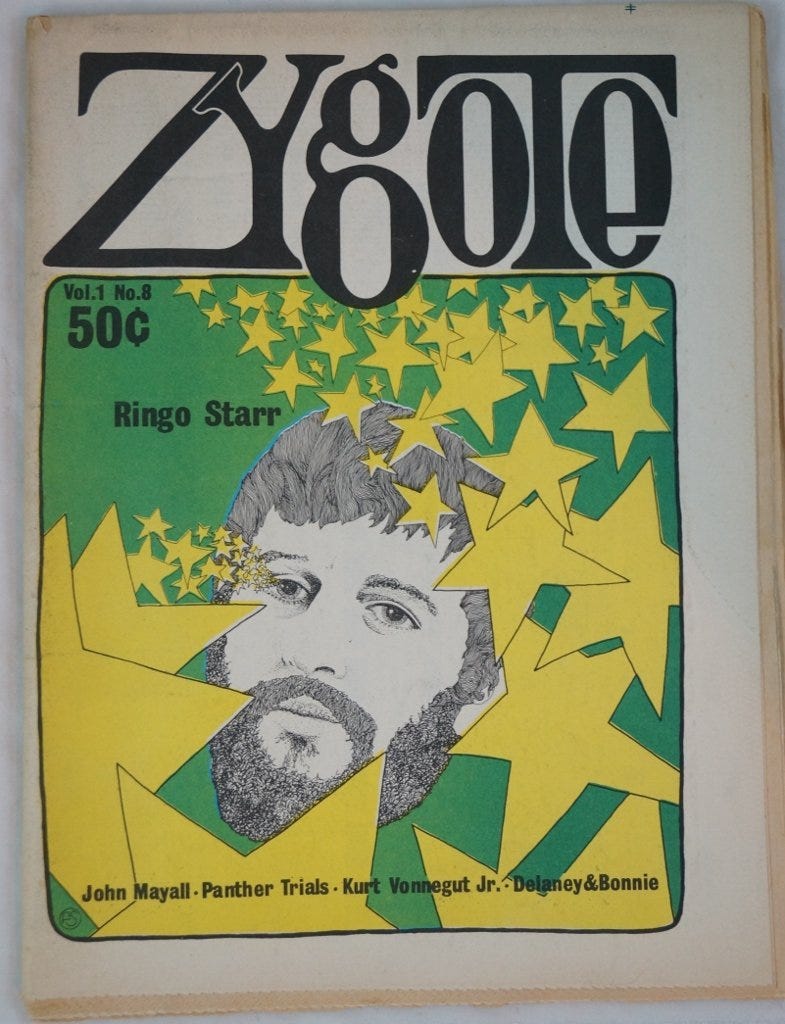

In June 1970, just out of college, I had turned down a chance for an instant career in daily newspapers to accept the (largely unpaid) position as writer and news editor at the new national “rock culture” magazine Zygote, sight unseen, via the usual ad at the Village Voice. Arriving in New York City, I found that it was a double-fold newsprint publication, like Rolling Stone, but with a boldly colored, illustrated cover in contrast to Stone’s high-quality black-and-white photos. I became “the Kid” in the office, as everyone else was, maybe, one year older.

When I arrived, the first issue had just hit the newstands. It was more political than Rolling Stone or Crawdaddy. Columns hit all the political bases, labeled “Women’s Lib,” “Page Left” and “Ecology Actions.” Features followed: A massive report from a festival starring Johnny Winter plus photos of nude girls and a Q & A with Woodstock hero Wavy Gravy. A two-page “Grass Grower’s Guide.” A writer, unaccountably, panned Astral Weeks by Van Morrison: “The music just doesn’t measure up…terribly repetitious vocal styles…The arrangements are awful…Sorry, Van. You tried. And so did I.”

Zygote visited areas of interest ignored by Rolling Stone at the time, including book reviews—e.g. John and Yoko’s Grapefruit—and a cooking section. (Soon I would be meeting Kurt Vonnegut and covering a Black Panthers trial.) The scatter-shot layout, however, made Rolling Stone look like Life. Also, there was a mere smattering of ads–-and the editor’s note apologized for the maiden issue being delayed 32 days. It had once contained some of John Lennon’s nude/sex lithographs. A printer refused to print it, and the magazine’s distributor said he would not carry such “filth.” Looking at the issue that did survive I had to assume that naked breasts, leftwing rants and odes to pot now passed the community standards test–-at least for my generation. Or so I hoped.

In July, I was assigned to cover my first New York area rock festival. I’d missed Woodstock the year before, but I had an honorable excuse: I had to work. I remember pulling wire copy that Saturday at the Niagara Falls Gazette and rushing it to the news desk, with frequent updates about the massive crowds, horrid weather, open drug use, and the closing of the New York State Thruway, but nothing about the music. So it was hard to feel, at that point, that I wished I’d gone, despite reports of widespread nudity.

The only quasi-rock festival I ever attended was Toronto Pop. It was a two-day affair but I only made it to one day (for Procol Harum, Steppenwolf, etc.) and it was held in a stadium with no overnight camping. Only about 20,000 attended each day, so I did not count that as a real festival experience, or close to it.

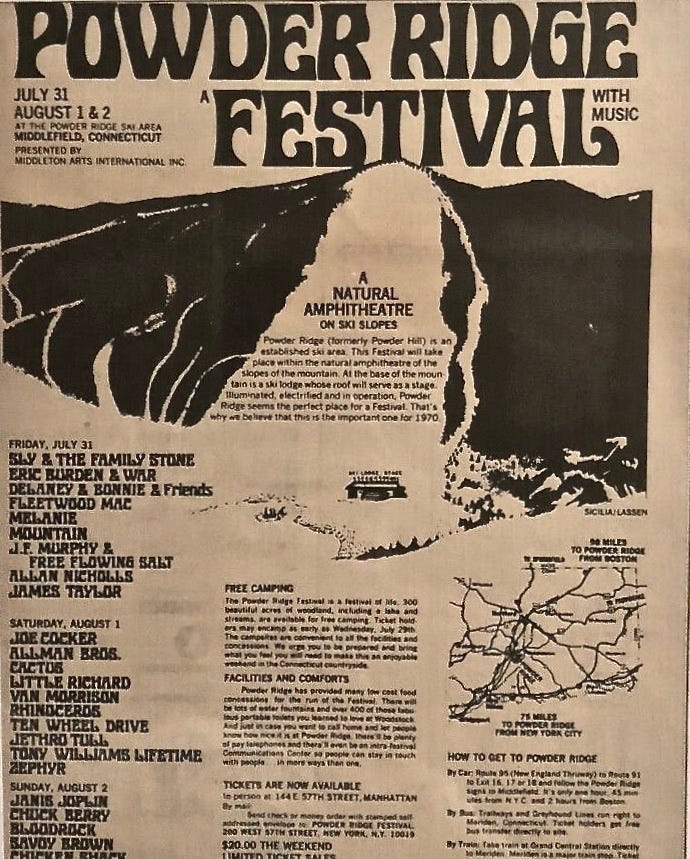

Now I was fairly thrilled to be sent to the massive Powder Ridge fest in Connecticut, and I’d finally get to see Van Morrison, Janis Joplin and the Allman Brothers live. Then I recognized one problem: I was not a back to nature person. I never did not like to camp out, even in a backyard tent. Also, there were rumors that the whole thing would get called off, perhaps after many people (e.g., me) got there. [Allmans from 1970, live, below.]

It was to be held at a ski area which the ads said formed “a natural amphitheater,” with the stage at the base of a lengthy slope. Tickets for the three days were $20. Day one, a Friday, got called off—goodbye Sly, the Family Stone and James Taylor—due to an injunction secured by residents in nearby Middlefield. (After Woodstock and Altamont the vast majority of fests were killed this way.) My publisher told me to go anyway. Thousands were already pitching tents and some musicians were vowing to show solidarity with the huddled, tripping, masses. The New York Times was covering the festival daily as a major local story. Would ticket-holders get stiffed? So I drove off on Saturday morning, August 1.

Ignoring signs posted on roads leading to the site reading “Festival Prohibited—Turn Back,” I arrived to find the parking wasn’t too crushed. Scattered across the slopes, looking down at an empty stage at the bottom, were 15,000 or more people, with the ratio of drug pushers to users about 3:2. (It would take more than an injunction to keep dealers away from long-haired rock fans.) Sellers of acid and mescaline posted signs next to tents advertising their wares—or was it “bewares”?

A buck for a tab was hard to pass up, though I did. I didn’t see, but heard about, the “electric barrel” where everyone was encouraged to toss extra tabs, and god knows what else, into a punch that you could then drink for free. Also: all utilities had been shut off and the food service abandoned. Porta-potties already reeked.

The “schedule” for day two, besides Van and the Allmans, had included Joe Cocker, Little Richard, and Jethro Tull, surely the largest collection of weirdos to ever perform on a single day in the great state of Connecticut. All were threatened with arrest if they actually showed up. No announcements came from the stage (since there was no electricity) so rumors were all we had. I roamed around, taking notes, spotting a nude couple here and there, some serious bad tripping in the woods, and the general odor of despair mixing with the smell of pot and day-old urine. We seemed to have the evil “brown acid” from Woodstock without the music or good vibes. (This was before cocaine became so prevalant so there were few jokes about “Powder” Ridge.) A 19-year-old woman from New Jersey was run over by a car near the festival site.

According to one published report:

One of the more sensational scenes, attested to by several witnesses, occurred in a small wood near some homes. A boy and a girl, both naked and approaching from different directions, met under the trees. On impulse they suddenly embraced. She dropped to her knees, he mounted her from behind, and after he had achieved his climax they parted—apparently without exchanging a word

Finally, in late afternoon, I felt I’d done my duty and beat a hasty retreat. The next day on the radio they reported that one artist did show: folk singer Melanie, who arrived after dark—hidden in a radio station’s van—and performed her hit “Candles in the Rain” as hundreds held up candles. She plugged into the only electrical generator near the stage—a Mr. Softee truck. [See her performing it, below, a few months earlier, with the Edwin Hawkins Singers.] “I got to sing,” Melanie would later boast. “I felt like I was Santa Claus. I didn't get arrested but it was a close call."

Sweet, but you couldn’t have paid me to stay for that—even though Zygote wasn’t paying me. A week later, Life magazine interviewed a doctor, a veteran of Woodstock, who counted “958 freakouts” he had treated.

Future stand-up comedian Lewis Black would later recount his LSD-soaked weekend at the Powder Ridge festival. He walked off his post as a parking attendant there despite enjoying the part where he got to wear an armband and be “The Man” for awhile. Black’s young career was paralleling mine, as he had just helped start an alternative mag in New Haven that aimed to become the “left-wing Reader’s Digest.” It quickly went belly-up when its funder left town to follow his guru.

A Black Panther leader, Lewis later claimed, gave a fiery speech at Powder Ridge just as a thunderstorm broke out—it was like “The Hall of the Mountain King”--causing many to blame the Panther and freak out even more. Black heard, or perhaps imagined, the Panther urging folks to “shoot the pigs,” starting with the parking lot fascists.

In any case, none of the attendees ever got their money back. Powder Ridge would go down in history as the most famous cancelled rock fest ever. Well, that was something anyway. In any event, my career as a journalist could only go up from there.

Song Pick of the Day

One of a couple of dozen fine Jason Isbell songs that he has written after cleaning up nearly a decade ago with help from wife Amanda Shires. This song was one of the first he wrote in this “comeback” and depicts how far he had fallen and why he sought recovery. Amanda joins in with singing and fiddling.

“Essential daily newsletter.” — Charles P. Pierce, Esquire

“Incisive and enjoyable every day.” — Ron Brownstein, The Atlantic

“Always worth reading.” — Frank Rich, New York magazine, Veep and Succession

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including the bestseller The Tunnels (on escapes under the Berlin Wall), the current The Beginning or the End (on MGM’s wild atomic bomb movie), and The Campaign of the Century (on Upton Sinclair’s left-wing race for governor of California), which was recently picked by the Wall St. Journal as one of five greatest books ever about an election. His new film, Atomic Cover-up, just had its world premiere and is drawing extraordinary acclaim. For nearly all of the 1970s he was the #2 editor at the legendary Crawdaddy. Later he served as longtime editor of Editor & Publisher magazine. He recently co-produced a film about Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.