Nick Kristof for Governor! Or Not?

The track record for authors getting elected is weak, from Upton Sinclair to Gore Vidal and Norman Mailer.

With Nicholas Kristof finally exiting The New York Times yesterday and announcing his candidacy for governor of Oregon (the less said about J.D. Vance in Ohio the better), I thought it was time to re-visit my exploration of how other prominent authors on the campaign trail have made out in the past— and the special traps on their road to Election Day. But first, Tom Petty confirms, live, that it is indeed “Good To Be King.”

Candidates With the Write Stuff

The track record for authors running for office is not very heartening — although nowadays almost every prominent national politician, when running for (or after leaving) office, simply must write a memoir or three, which often rocket to near the top of the bestseller list.

Many years ago I wrote a lengthy piece on this subject for the The New York Times Book Review, which started on its front page then kicked inside. My award-winning book, The Campaign of the Century, on the most notable such race ever — Upton Sinclair’s nearly successful “End Poverty” crusade in California in 1934 — had recently been published. (It was later named by the Wall St. Journal as one of the five best books ever on an election campaign.) Eventually it would inspire a key plot point in David Fincher’s Mank, which I also wrote about not long ago for the Times.

Here are excerpts from my earlier essay for the Times. To read it all, go here.

“I’d like to see how a man looks who’s given up his typewriter for the microphone,” John Dos Passos wrote Upton Sinclair on Oct. 1, 1934. Sinclair was running for governor of California, and Dos Passos, who was in Hollywood completing a screenplay for Josef von Sternberg, wanted to visit his old friend in Pasadena and play anthropologist for an afternoon.

The author in American politics is a rare species indeed, perhaps even an endangered one. Yet writing well and running for office are not necessarily incompatible. One must acknowledge Jefferson and Lincoln and Grant, for example. Mario Cuomo is an elegant diarist. Still, one does not think of these men as authors first. And Ted Sorensen did ghost write most of John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage. Literary figures in the United States generally are content to criticize the political process from outside the ring.

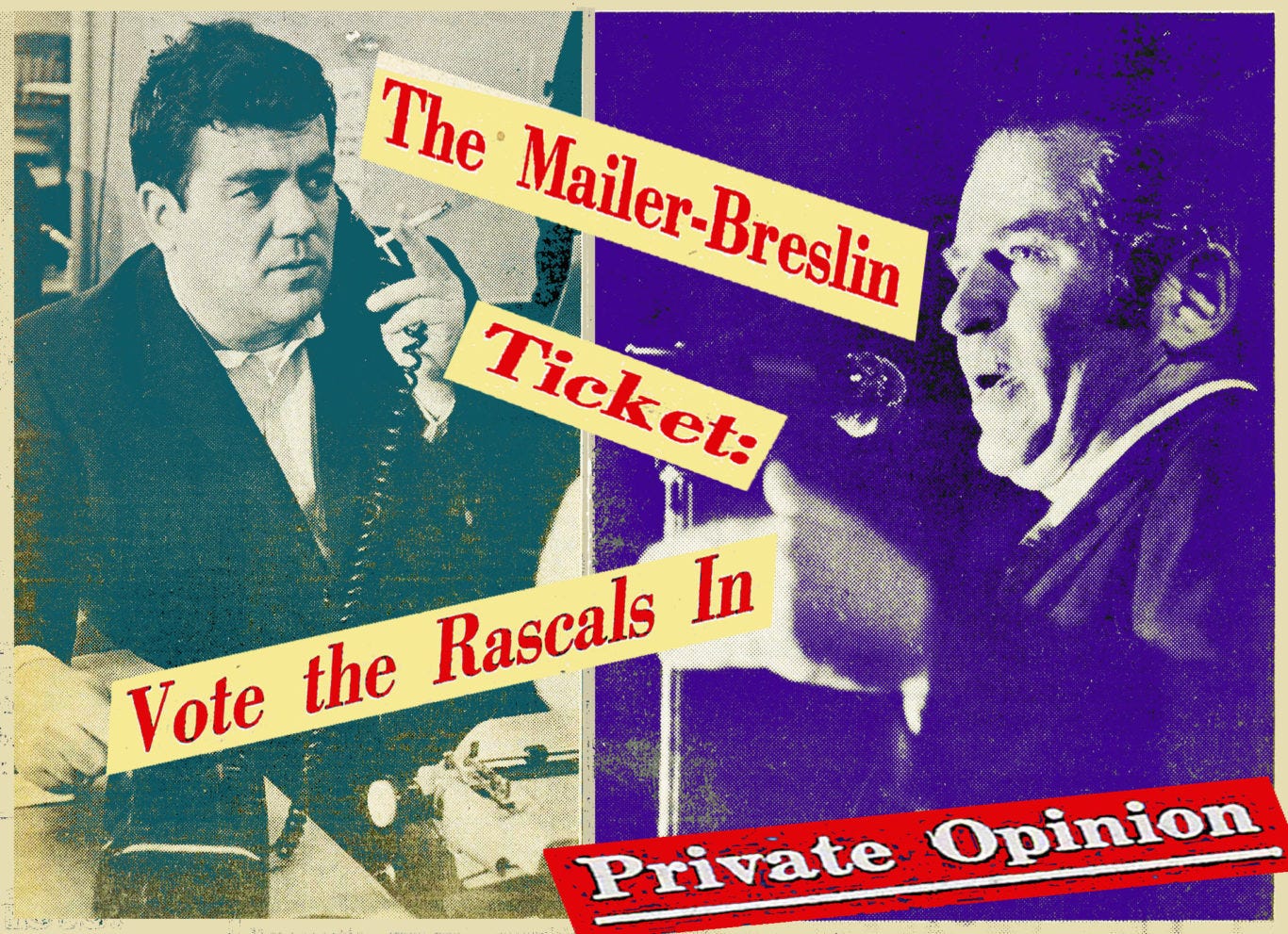

Perhaps the most recent memorable exception is Norman Mailer’s race for Mayor of New York in 1969 — a blustery effort that ended in resounding defeat. His running mate, the columnist Jimmy Breslin, who was seeking the post of City Council President, also lost.

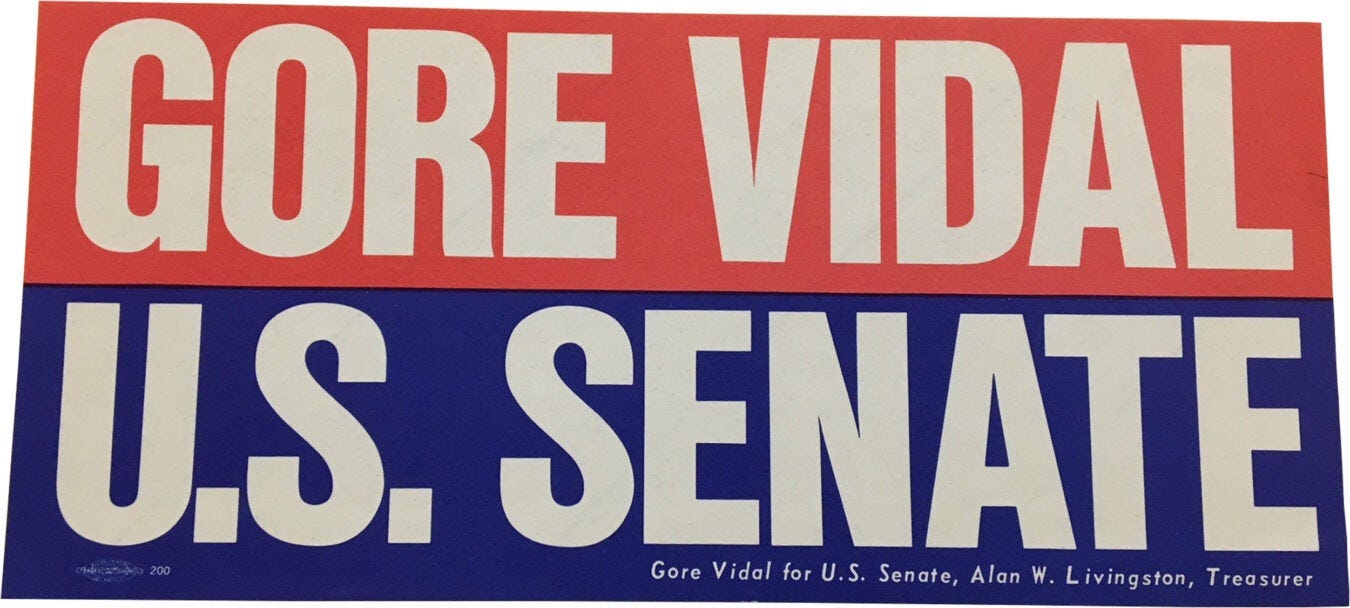

The living author most frequently linked to electoral politics is Gore Vidal. Grandson of a senator from Tennessee, Vidal campaigned unsuccessfully for the House of Representatives in New York in 1960 and for the United States Senate in California in 1982. Vidal has threatened to run on other occasions. In a wonderful example of art fulfilling ambition, he plays a pompous Senator in Tim Robbins’s terrific film Bob Roberts.

If an actor like Ronald Reagan (or later a reality show clown) actually achieve it — why not a celebrated author? For an answer, one must examine what happened to Upton Sinclair in 1934, when he waged the most remarkable campaign ever conducted by an author, only to be “licked . . . by his own typewriter,” as the newspaper columnist Westbrook Pegler put it.

No American writer had converted more young people to socialism. “Upton Sinclair first got to me when I was 14 or so,” Kurt Vonnegut remembered. At about the same age, Norman Mailer read Sinclair’s novel Boston (an exploration of the Sacco-Vanzetti case) and “for better or worse,” he later reported, “it moved me to the left.” Saul Bellow also remembered that Sinclair’s books made a profound impression on him in his youth, even though he understood right from the start that the author was “something of a crank — one of the grand American cranks who enriched our lives.”

Like Norman Mailer, Upton Sinclair was often in the news for reasons that had little to do with writing: getting arrested, financing films or striving for office. Twice he ran for Governor of California on the Socialist Party line and barely made a ripple. Then, in the autumn of 1933, at the age of 54, he decided to seek the governorship again, this time as a Democrat. Despite the coming of the New Deal, the Great Depression was deepening in California; Sinclair felt he had a chance to win. “You have written enough,” he later remembered saying to himself. “What the world needs is a deed.” (Sinclair, below, during the campaign.)

First, he wrote one more book, I, Governor of California, and How I Ended Poverty. In this fantasy, a certain well-known muckraker, Upton Sinclair, proposes a 10-point program to “End Poverty in California” (EPIC). The plan inspires a mass movement that carries him to victory in the 1934 Governor’s race. After a few months of hard work, Governor Sinclair succeeds in abolishing poverty by soaking the rich and putting the unemployed to work on foreclosed farms and in abandoned factories. Then he retires, returns to Pasadena and picks up his pen again.

When Sinclair announced his candidacy for real, he observed that “this is the first time a historian has set out to make his history true.” And, to a point, he succeeded: I, Governor sold tens of thousands of copies and the most powerful social movement in California’s history, known as the EPIC crusade, rallied to his cause. “California’s a great place right now,” John Dos Passos informed Malcolm Cowley. “You can look out the window and watch the profit system crumble.” On Aug. 29, 1934, Sinclair swept the Democratic primary in a landslide, and most political pundits predicted that he would easily brush aside his lackluster Republican opponent, Gov. Frank F. Merriam, in November.

“I cannot tell you how unreal the world of books seems to me now,” Sinclair told Floyd Dell, his biographer. “I doubt if I ever write any more books!” A screenwriter named Frank Scully wrote an article for Esquire called “Author! Author! for Governor,” observing that it was quite a novelty to have a political leader who not only could read and write, “but knows what the country needs, and can even spell it!”

Many of Sinclair’s literary friends on the left, including Archibald MacLeish and Dorothy Parker, supported him passionately. Heywood Broun, who in 1930 had run for Congress as a Socialist in Manhattan — finishing a poor third — wrote a column for the New York World-Telegram mocking the Los Angeles Times for equating Sinclair’s supporters with maggots and termites.

Another Sinclair booster, Theodore Dreiser, had unresolved electoral ambitions of his own. Since achieving enormous popularity with his novel An American Tragedy in 1925, he had drifted toward the Communist Party and briefly considered running for Governor of New York. Responding to Sinclair’s triumph in California, Dreiser wrote a lengthy piece for Esquire calling EPIC “the most impressive political phenomenon America has yet produced.”

Like Dreiser, Lincoln Steffens was a fellow traveler who supported Sinclair from the left. He also had been urged to run for office in California in 1934 — those were the days for writers! — either on the Communist Party line (for Governor) or as an EPIC candidate (for United States Senator). But Steffens, who lived in Carmel, was ill.

From Rapallo, Italy, Ezra Pound weighed in with yet another endorsement. “Congrats on nomination,” Pound wrote Sinclair. “Now beat the bank buzzards and get elected.” Pound was busy promoting Mussolini, writing essays with titles like “ABC of Economics” and calling Fascist Italy “freer than anywhere else in the Occident.” Pound also wished to play a role in American politics. He asked Ernest Hemingway if he knew a way he could make money writing campaign songs for political candidates; twice he wrote to Franklin D. Roosevelt, offering economic advice to spur the “Nude Eel.”

Like nearly everyone, Pound admired Sinclair’s fighting spirit, but he considered him a “polymaniac” with too many “fixations.” He urged Sinclair to “git on with gettin elected,” but called the candidate “a bloody ass” for not renouncing “doles and relief.”

H. L. Mencken also felt ambivalent. Sinclair was a puritan, a champion of the common man; Mencken was the free spirit who had coined the expression “the booboisie.” Mencken had once called Sinclair an “incurable romantic, wholesale believer in the obviously not so. The man delights me constantly. . . . I know of no one in all this vast paradise of credulity who gives a steadier and more heroic credit to the intrinsically preposterous.”

The two writers were irreconcilable, yet they liked and respected each other enormously; they conducted a lively correspondence amounting to more than 150 letters. “I am against you and against the Liberals because I believe you chase butterflies,” Mencken had informed Sinclair a few years earlier, “but I am even more against your enemies.”

By 1934, however, Mencken was often finding common ground with anti-New Deal conservatives. “Sinclair has been swallowing quack cures for all the sorrows of mankind since the turn of the century, is at it again in California, and on such a scale that the whole country is attracted by the spectacle,” Mencken commented in The Baltimore Sun. Still, he hoped Sinclair would win in November. “It is always amusing to see a utopian in office,” Mencken observed, “and this one is far bolder, vainer and more credulous than the general.” Sinclair, stung by Mencken’s barbs, replied that his old friend might be “brilliant with words, but just now we need action, and his witticisms do not fill the stomachs of the hungry.”

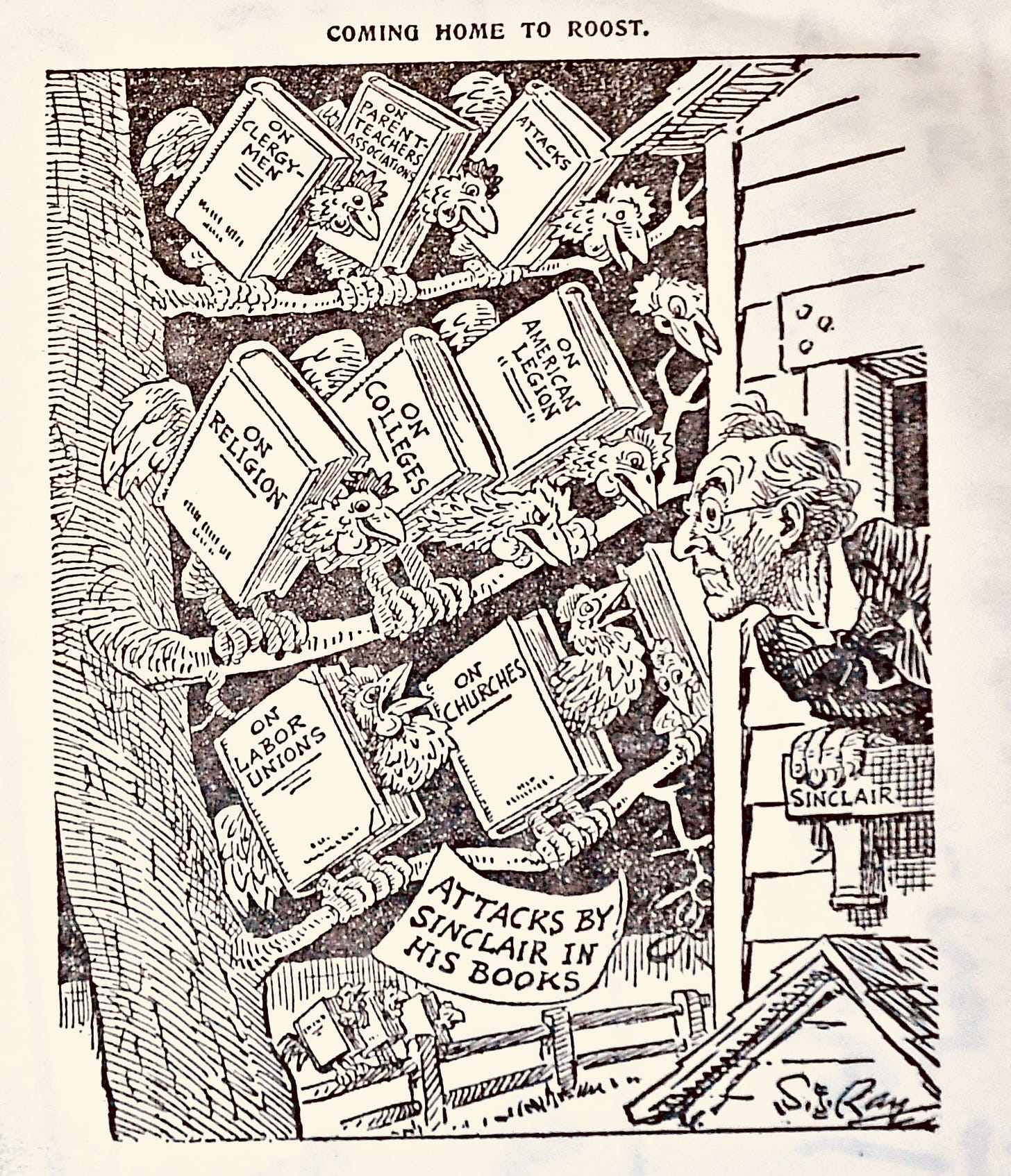

For a few weeks it appeared that Sinclair might get elected. But the Republican operatives soon conceived a winning strategy. Sinclair had used his fame and skill as an author to launch his campaign. Now Sinclair’s opponents would turn his reckless career as a muckraker against him.

To find out what happened next: go here.