Nolan's "Oppenheimer" Emerged One Year Ago: But What About First A-Bomb Movie?

The real-life "Oppie" played a shameful role in the MGM drama.

Greg Mitchell is the author of more than a dozen books including “The Tunnels” and “The Campaign of the Century” (see link) and now writer/director of three award-winning films aired via PBS, including “Atomic Cover-up” and “Memorial Day Massacre” (recently nominated for an Emmy). You can still subscribe to this newsletter for free.

On this weekend exactly one year ago, I was invited with a few dozen others to the first screening in New York City of Christopher Nolan’s upcoming movie “Oppenheimer.” Nolan sat on a panel afterward and later socialized in the lobby of the mini-theater (in the basement of a midtown hotel). I had just launched my newsletter devoted to the movie, the issues raised and ignored in it, and Oppenheimer and his legacy (this sibling Substack is still going, where you can subscribe for free). Here is a piece I wrote back then published elsewhere, at Mother Jones. It is adapted from my book on the horrific first Hollywood movie on the making and use of the atomic bomb.

_______________

Famed physicist, so-called “Father of the Atomic Bomb,” and alleged national security risk, J. Robert Oppenheimer, has been portrayed on the screen in fictionalized dramas for more than seventy-five years, long before director Christopher Nolan put him at the center of his upcoming movie epic.

There was Sam Waterston’s much-honored depiction in the seven-part Oppenheimer series in 1980 for PBS. Nine years later, Roland Joffe’s big-budget studio drama, Fat Man and Little Boy, foolishly pitted little-known Dwight Shultz against mega-star Paul Newman as a bullying Gen. Leslie Groves, the Manhattan Project’s military director. That same year, David Strathairn portrayed him in the TV movie Day One, and later in a PBS “American Experience” episode on the physicist’s security clearance ordeal, The Trials of J. Robert Oppenheimer. More recently, in the little-seen (co-star Rachel Brosnahan had not yet become Mrs. Meisel) WGN series, Manhattan, from 2014, Oppenheimer was a fringe character and again played by a little-known actor, Daniel London.

Now, in Nolan’s Oppenheimer, he gets the star treatment, in the form of charismatic Cillian Murphy. But what all of these wildly varying depictions and story lines have in common is this: By the time they were created, Oppenheimer himself was no longer living. He could not advise, inform, or approve.

Sadly, the MGM producer of the one major screen drama that did appear in his lifetime—in fact, very soon after the first two atomic bombs fell over Japan—sought his input and approval, and in this crucial role, Oppenheimer acted disgracefully. At the same time, meanwhile, he was already being tailed and bugged by the FBI, suspected of hiding a Communist Party past or at least harboring Red sympathies.

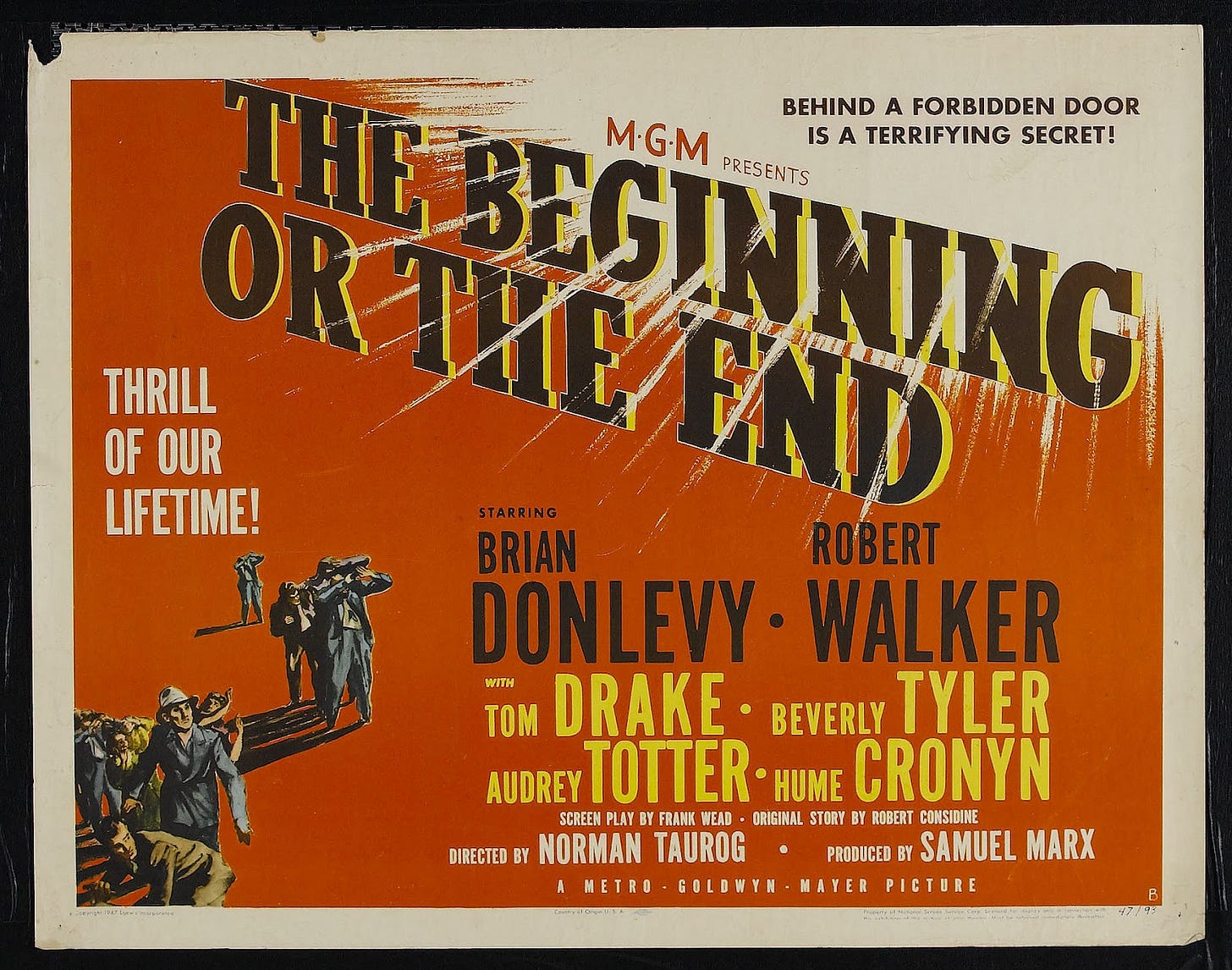

MGM had started work on a drama, titled The Beginning or the End, inspired by the pleas of atomic scientists, who demanded that Hollywood make a major movie urging the U.S. to turn away from building more powerful weapons, which would likely spark a nuclear arms race with the Russians and imperil the entire world.

Soon, MGM would launch a big-budget project, with studio co-founder Louis B. Mayer calling it the "most important" movie he would ever produce. In the year that followed, however, the original message of the MGM movie would shift almost 180 degrees, and introduce major (in some case, comical) falsehoods, ending as little more than pro-bomb propaganda. Both President Harry S. Truman and General Groves were given script approval, and ordered dozens of cuts and revisions. Truman even forced a costly re-take and got the actor playing him fired.

More troubling for MGM, the studio had to convince the key people in the bomb project to sign releases granting permission to be portrayed in the film. This led to attempts over many months to get Albert Einstein, Leo Szilard, and Oppenheimer to approve, while promising them (unlike with Groves) no fee, to little avail.

And no wonder. MGM was so anxious to please Washington it would order script revisions, at various points, that would include these fictionalizations: The Japanese would be said to be on the verge of developing their own atomic bomb—at a lab in Hiroshima, no less; an American scientist would receive a fatal dose of radiation while arming the Hiroshima bomb, then appear to his wife as a ghost assuring her that our nuclear future was “so bright”; Hiroshima was showered with warning leaflets before the bomb was dropped. And so on.

After weeks of pressure, Einstein and Szilard finally succumbed, even while believing the movie's script was very poor, but the ever-conflicted Oppenheimer resisted. Prepared for the worst, MGM had changed his name in one version of the script to the implausibly WASPY “Whittier.”

Oppenheimer was certainly open to persuasion. Paramount had launched a competing movie, Top Secret, and Oppenheimer had sat for two interviews with the screenplay writer—Ayn Rand. The studio would eventually drop the project, after Rand had penned fifty pages of the script.

On April 18, 1946, producer Sam Marx sent Oppenheimer a copy of the screenplay with the hope he would at least “glance through it” before they met three days hence in Berkeley. The latest movie scenario had the Oppenheimer (or Whittier character) introducing the film, then playing a major role in it.

That Saturday night Marx departed the Palace Hotel in San Francisco for Oppenheimer’s rambling one-story villa overlooking the bay in Berkeley. After dinner, Oppie spoke frankly about the script, in his usual manner. In a letter to his friend J.J. Nickson he would recount much of this discussion. Based on that, it went something like this:

Oppenheimer: “Some of the themes in the movie are sound, but most of the supposedly real characters like [Enrico] Fermi and myself are stiff and idiotic. When Fermi hears of fission he says my what a thrill and my most characteristic phrase was gentlemen, gentlemen, let us be calm.”

Marx: “I understand.”

Oppenheimer: “Most of the trouble rests in ignorance and bad writing, rather than in anything malign.”

Marx: “Well, that may be true, but look at these newly signed agreements by Fermi and a few others.”

Oppenheimer: “Well, what kind of agreement can you and I make? For example, how about hiring as technical adviser my former aide and Los Alamos historian David Hawkins? Also, I want to be portrayed as a friend of that ethical scientist, what’s his name, Matt Cochran.”

Marx: “Okay on all that. In addition, we will correct all of the factual errors you mentioned and take seriously all of your other gripes and proposed additions. Let’s shake on it.”

Oppenheimer would tell Nickson that he found his visitor from Hollywood “honestly eager to get the script improved,” but even after the revisions, Oppie predicted “It won’t be very good.” (In fact, Marx’s changes were minor and the script would only get more flaky, but Oppenheimer apparently did not follow up

.) At least in the current story, he added, the scientists seemed to be treated as “ordinary decent guys, that they worried like hell about the bomb, that it presents a major issue of good and evil to the people of the world.” He concluded: “I hope I did right. I think the movie is a lot better for my intercession, but it is not a beautiful movie, or a wise and deep one. I think it did not lie in my power to make it so.”

After caving, and giving the misguided MGM project a major and somewhat unexpected boost, Oppenheimer seemed uncommonly insecure. “Let me hear from you,” he asked Nickson, “particularly if you think I did wrong or want me to try again.” He had other things to worry about as well. The FBI had started tapping the phone in his Berkeley home and recording the conversations.

While the studio had decided on the accomplished, but not A-list actor, Hume Cronyn (who hailed from Canada) to play him, that still might change. Marx doubted they could find a better actor, but they could certainly secure a more impressive movie “name.”

Fawning over his new friend, Marx assured him in a letter that he had impressed on the film's writer, Frank Wead, and director Norman Taurog, “that the character of J. Robert Oppenheimer must be an extremely pleasant one with a love of mankind, humility and a pretty fair knack of cooking.” He closed: “I would rather see you pleased with this picture than anyone else who has been concerned with the making of the atom bomb.” It never hurt anyone to appeal to Oppenheimer's vanity.

Two weeks later, near the end of a lengthy phone conversation—taped as usual by the FBI—Kitty Oppenheimer informed her husband, who was in the east, that he had received a letter from a "Hugh Cronin" (as the name was recorded in the transcript), "explaining why he would like to be you." In the letter, Cronyn mocked the MGM script but promised to do his best in portraying Oppenheimer.

"Well, I'll tell you what I did on this," Oppenheimer replied, then referred to General Groves' top aide. "This very ugly creature, [Colonel W.A.] Consodine, called me and said that Marx had said it was all right and would I sign the release, and I said sure. I got the release and I signed it with a paragraph written in saying that all of this is subject to my receipt of a statement from Mr. Sam Marx that he believes the changes that have been made are satisfactory."

Kitty: "Oh."

Robert: "Well, I didn't think there was anything else to do. I don't want anything from them and if I can work on his conscience, that is the best angle I have. It just isn't worth anything otherwise, darling."

At this juncture, the call faded in and out. "The FBI must have just hung up," Robert quipped.

The transcript recorded Kitty's response as: Giggles.

Then Robert concluded: "The only thing we can do there is to try to persuade them to do a decent job."

A few days later, Oppenheimer would visit the movie set in Hollywood, meet Cronyn and view a rough cut of the film. His only recorded note was complaining that the bomb was raised to the top of the tower at the Trinity test site far too fast.

The movie would flop when released the following February—Oppenheimer was invited to the gala premiere but failed to attend--and fade from importance, but FBI surveillance of Oppenheimer would continue off and on for years. That probe would culminate in the famous 1954 hearing leading to Oppenheimer losing his security clearance, which led to his steady decline in influence and voice in the national discourse on the further development of nuclear weapons and policy.

More on the book and ordering.