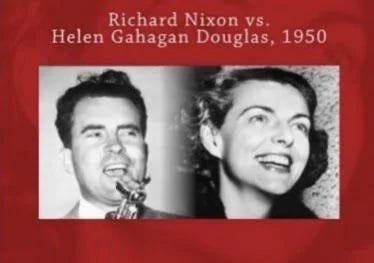

Part II: Nixon vs. Douglas 1950 (and Trump vs. Harris Today)

Another excerpt from book, plus cartoons on current campaign.

Greg Mitchell is the author of more than a dozen books including “The Tunnels” and “The Campaign of the Century” (see link) and now writer/director of three award-winning films aired via PBS, including “Atomic Cover-up” and “Memorial Day Massacre” (up for an Emmy later this month) . You can still subscribe to this newsletter for free.

A couple of days back I offered an excerpt from my (ever more relevant) book “Tricky Dick and the Pink Lady,” on how Nixon destroyed groundbreaking Rep. Helen Gahagan Douglas in the 1950 race for the U.S. Senate in California (largely via sexism and Redbaiting). The seat was later won by Kamala Harris. Of course, Harris faces a torrent of dirty tricks and vile personal attacks in the months ahead, although modern “Redbaiting” runs more along the lines of being mocked as an “ultra-liberal.” It is the GOP which is far more friendly to Russia and Putin today.

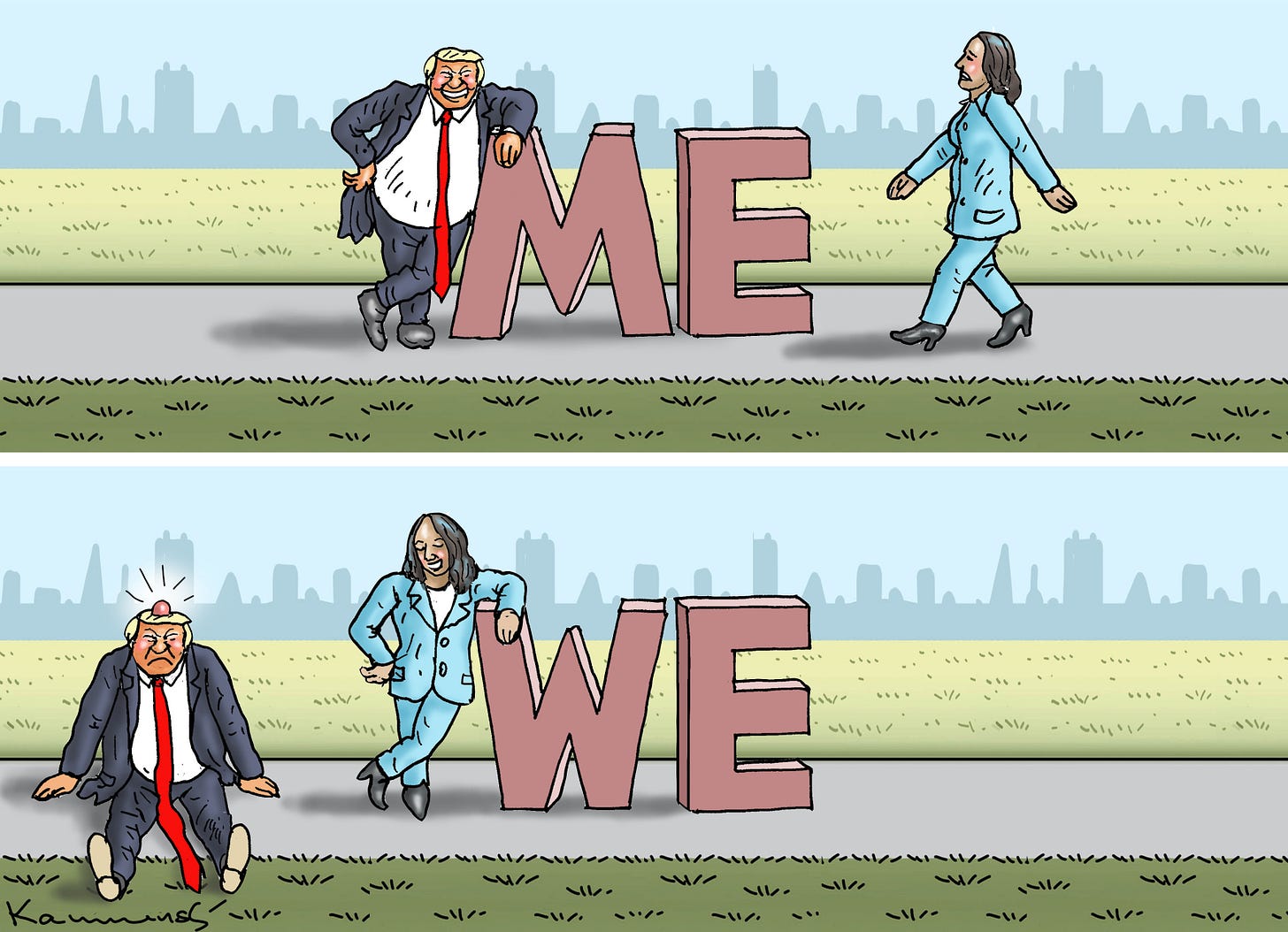

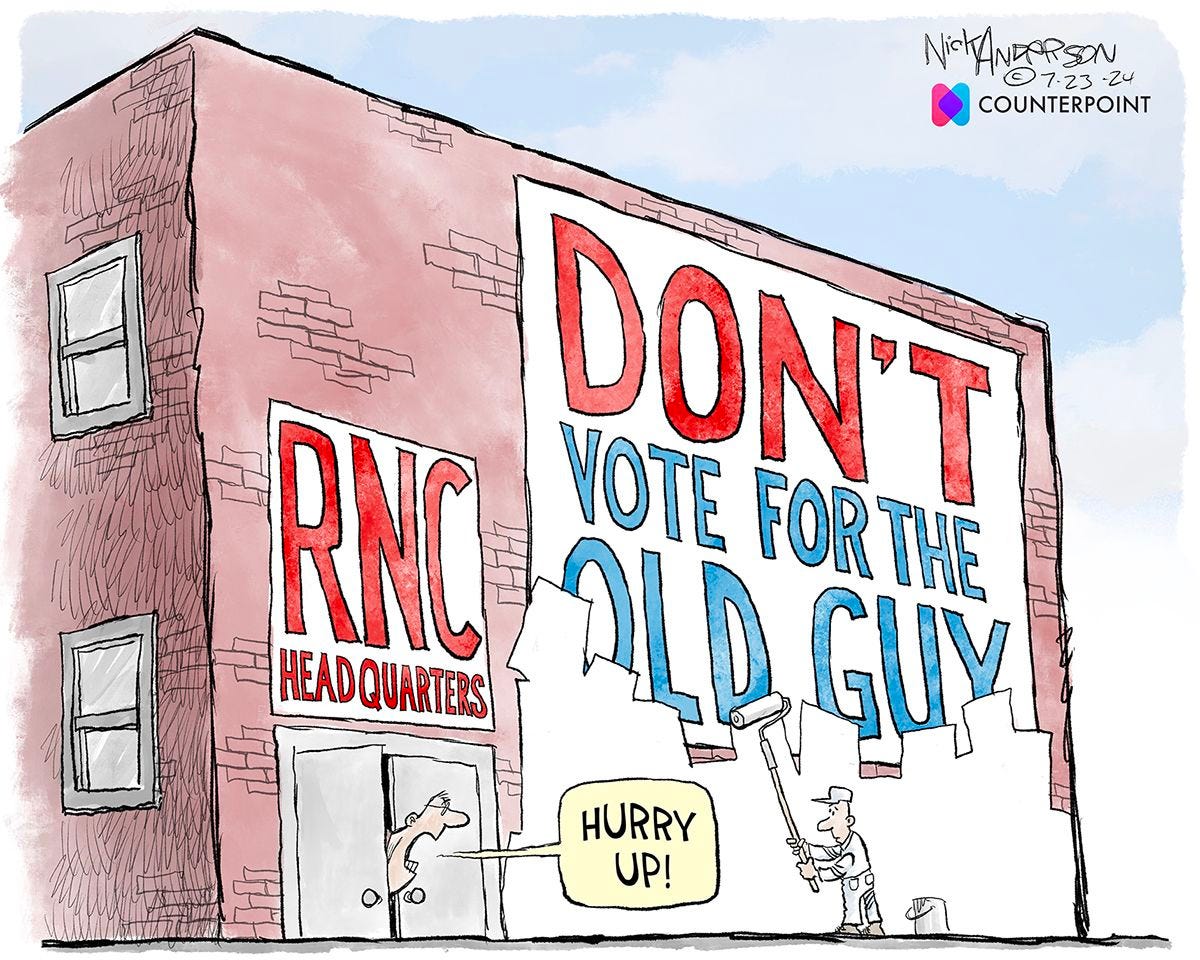

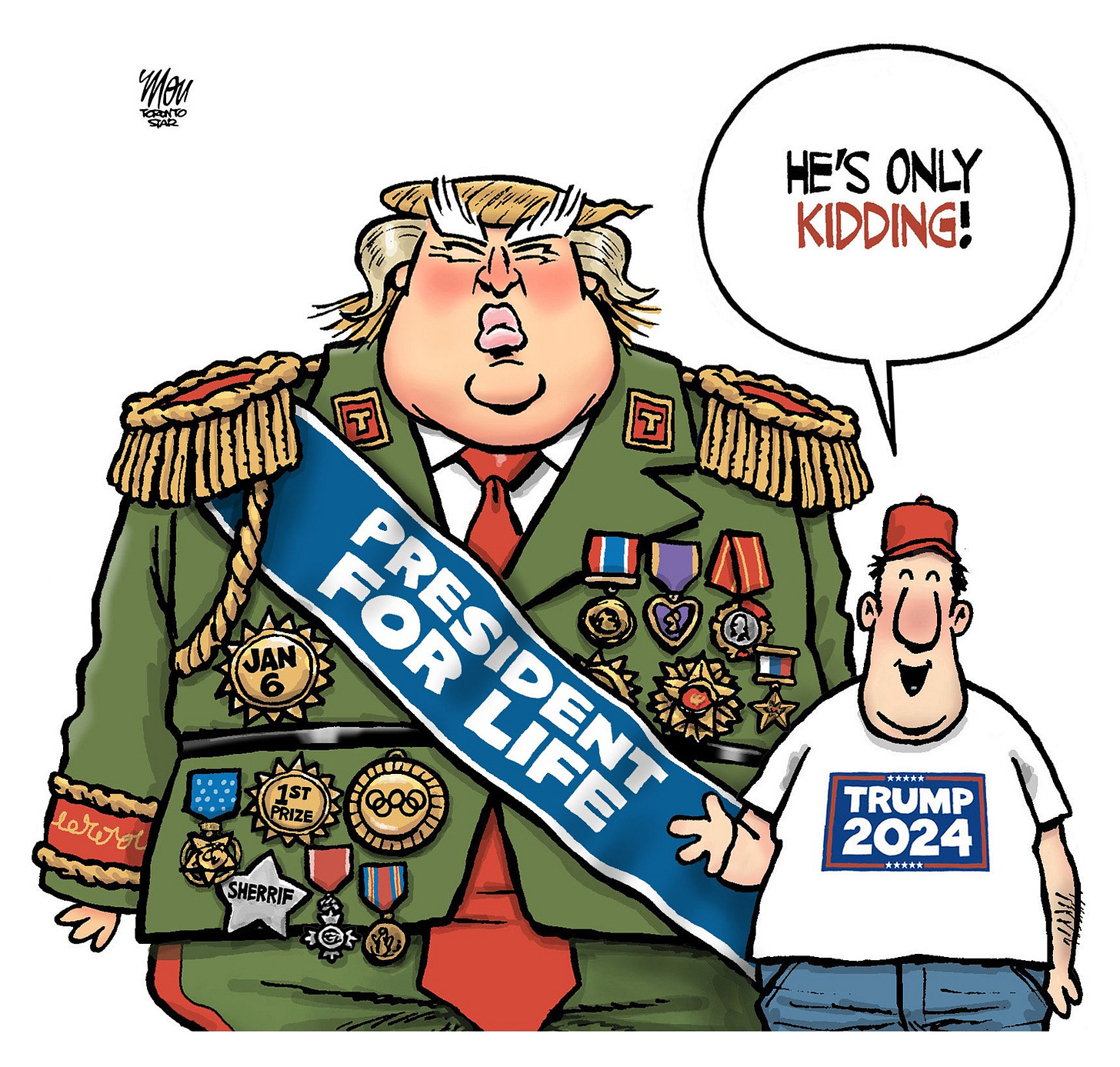

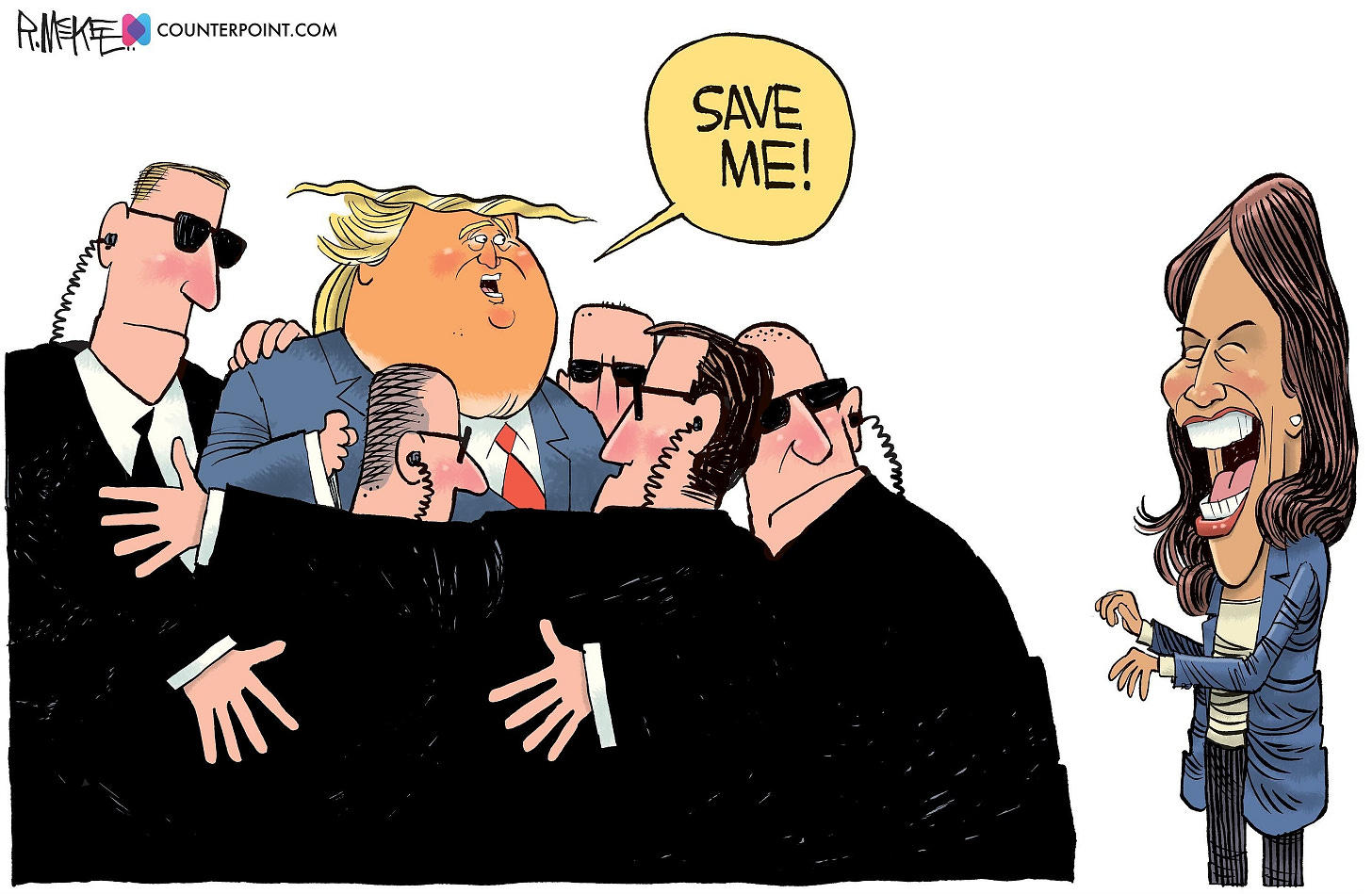

Anyway, see Part II below. But first, a few cartoons on the current campaign. You can still subscribe for free.

Part II: Nixon Vows, “I’ll Castrate Her”

(More from “Tricky Dick and the Pink Lady.”)

As they visited friends on primary day, Richard Nixon and his pretty wife, Pat, radiated happiness and confidence. Dick Nixon appeared certain to win more than 90 percent of the Republican vote. Nixon knew that his campaign against Helen Douglas would be well managed and well financed, and the most grueling period was already past: his travels up and down this cruelly distended state in a yellow wood-paneled station wagon, journeying fifteen thousand miles to deliver more than six hundred speeches in fifty counties. And that was for a one-sided primary contest. The rest of the campaign would be a war; it would be for all the marbles; it would pit him against a strong, worthy, but highly vulnerable candidate (a woman no less)--meaning, in political terms, it would be challenging, fascinating, possibly even fun.

"There is only one way we can win," Nixon had vowed. "We must put on a fighting, rocking, socking campaign."

California would also host the most closely watched governor's race in the country: two-term incumbent Earl Warren against young James Roosevelt, FDR's son. The survivor would become a favorite in the 1952 presidential race (Harry Truman had privately decided not to run for reelection). The winner of the state's Senate contest would no doubt be considered for the second spot on a ticket. A boomlet for Douglas for vice president at the 1948 Democratic National Convention "heralded what may happen sooner than we think, even possibly in 1952," The Washington Post had observed, and Nixon was clearly a hot prospect on the other side.

"Mrs. Douglas takes wholeheartedly after the Administration's program," Richard Nixon remarked on primary day, "one hundred percent plus, including such things as socialized medicine." That evening, Nixon and his family checked the early returns at City Hall in downtown Los Angeles, then celebrated at election headquarters on the second floor of the Garland Building over on West Ninth Street. His vote of more than 740,000 exceeded even his high expectations as his two minor GOP challengers mustered less than 35,000 between them. More significant, however, was Nixon's tally in the Democratic column: more than 300,000 votes. This suggested that his attacks on Truman and other Democrats as unwitting allies of the Soviets had paid off and should be pressed even more intensely in coming months.

"I welcome Mrs. Douglas as an opponent," Nixon announced. "It won't be a campaign of personalities but of issues." Douglas would have to reveal where she stood on those issues, "or," he added ominously, "I'll do it for her."

Most of Nixon's advisers felt that Douglas would be a formidable foe; she was as brave and as energetic as their man, with twice the charisma. For the record, Nixon concurred, calling her "a colorful, aggressive, vote-getting candidate" who had long been underrated by the "wise boys" of politics. But privately, he and campaign strategist Murray Chotiner felt otherwise. If Senator Downey had run for reelection, the outcome, they believed, would have hinged on farm issues, not on the Communist threat. But that all changed with Downey out. Nixon and Chotiner wanted Helen Douglas to win the nomination because her liberal politics played into the freedom-versus-socialism theme they had already decided would dominate the campaign.

"There's no use trying to talk about anything else," Nixon told his northern California chairman, "because it's all the people want to hear about." This was sure to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

During their travels across the state that spring, Nixon and Douglas had rarely crossed paths. Douglas, aware of her rival's talent as a debater, avoided joint meetings. One day, however, they appeared separately in a small town in the north. Nixon's aide Bill Arnold went out to hear what she was saying, came back, and reported to his boss. This was during a phase when Douglas, angered by Nixon's gibes, sometimes lost her composure and referred to him as a "peewee" who, like Joe McCarthy, was trying to get people so scared of communism they would be afraid to turn off the lights at night.

When he heard what she had said, Nixon muttered, "Why, I'll castrate her!" That would be literally impossible, Arnold pointed out. "I don't care," Nixon responded, "I'll do it anyway!"

As a woman, Helen Douglas was particularly vulnerable to charges that she lacked the toughness to oppose the Communists. But Chotiner reminded his candidate, "You can't get into a name-calling contest with a woman. The cost in votes would be prohibitive." Still, Nixon would later admit that Douglas's emergence on the Democratic side "brightened my prospects considerably."

On primary night, Helen Douglas, dressed in a simple black dress--but still movie-star radiant--joined her mostly female staffers at her Los Angeles headquarters. She had won a solid victory, defeating Boddy by a two-to-one margin and rolling up more than 150,000 votes in the GOP primary. Her supporters, true believers, responded with whoops and hugs, as if she had already won the election. She asked much, sometimes too much, of her aides, but they remained devoted to her. Some of them felt that the voters (particularly women) admired what Douglas stood for, and she was a fabulously vibrant campaigner, so there was no way she could lose.

The candidate's personal satisfaction on primary night was marred by an uncomfortable moment at headquarters involving a male volunteer, a Greyhound bus driver who demanded a private conference with her. She soon discovered that he was more interested in sexual favors than political favors. Douglas knew that the passions of a campaign often become sexually charged but still faulted herself for not recognizing the bus driver's agenda earlier.

Before returning to the home she shared with her children and husband in the hills high above Los Angeles, she stopped at several local campaign headquarters. Paul Ziffren, the well-known attorney and one of her chief fund-raisers, finally drove her home, and Douglas, all business, asked him to make sure to thank Eleanor Roosevelt and others for their help. Then she prepared to catch a few hours' sleep--alone. Her husband Melvyn Douglas was on the road, appearing in a play called “Two Blind Mice,” which had opened in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and now Chicago.

Unlike many of her supporters, Douglas knew she was far from a shoo-in. Simple arithmetic told her that Nixon's combined vote in the GOP and the Democratic primaries exceeded one million, whereas hers did not quite reach nine hundred thousand. This in itself was not fatal, for the Democratic turnout would likely soar in November.

But there was something more troubling. For nearly four years, she had observed her colleague Richard Nixon at dose range in Congress, and she knew him to be smart, dynamic, daring, a formidable speaker--and out to win at almost any cost. A reporter for a Democratic paper called him "Whittier's tall, dark and handsome gift to the Republican party." Now she had received a letter from a member of Students for Douglas at the University of California at Berkeley. Nixon had spoken at Sather Gate, and the student was surprised to hear him give a "magnificent" speech. "He is one of the cleverest speakers I have ever heard," he warned:

The questions on the Mundt-Nixon bill, his views on the loyalty oath, and the problem of international communism were just what he was waiting for. Indeed, he was so skillful--and I might add, cagey--that those who came indifferent were sold, and even many of those who came to heckle went away with doubts.... If he is only a fraction as effective [elsewhere] as he was here you have a formidable opponent on your hands.

The student added that Nixon based his entire campaign on foreign policy and "would like nothing better than to draw you into a dispute with him over communism. On that question, I venture to say, he is rhetorically impregnable, but the rest of him is all Achilles' heel. Hit him on the home front, and hit him hard."

The letter was remarkably astute. Douglas, in reply, told the student that his report corroborated what she had heard from others. "I think you are quite right," she observed, "and will act accordingly." As Helen Douglas retired on primary night, she knew that if she let her gifted opponent call the shots in this campaign she had no chance of becoming just the fourth woman ever elected to the U.S. Senate.