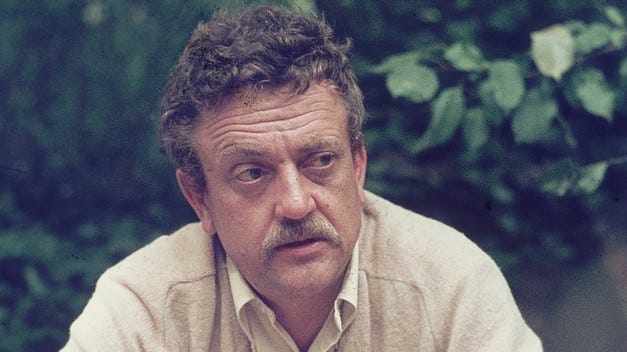

Playing With Kurt Vonnegut, 1970

The latest installment from my memoir-in-progress: An Off-Broadway meeting with my novelist hero (at that time) to talk about his anti-war play.

For the next installment in my weekend walks down memory lane (earlier ones covered my first Dylan concert, getting my job at Crawdaddy in 1971 and driving with Springsteen to my hometown), I offer this encounter with Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. He had just emerged from cult to bestselling status. This was during my first magazine job in New York, at the immortal Zygote. It does go on, so I will publish Part II tomorrow or Monday. And down the road a bit, I will bring you the story behind my interview with him four years later and the rather famous article that ensued. (Or you can read all that and more in my little e-book, Vonnegut and Me.) But first, for Easter weekend, Leon Russell’s “Roll Away the Stone.” For a more sacred take, catch Beethoven way down below….Don’t forget to comment, share or subscribe (it’s still free).

Off-Broadway With Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

Like so many of my generation (perhaps too many, in the view of some), I adopted Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., as my favorite author during high school, in the mid-1960s, after kicking to the curb my J.D. Salinger and Ian Fleming addictions. My friend Paul turned me on to Cat’s Cradle, a fast and funny paperback read, and that was that. Soon I’d devoured most of his other novels, with Mother Night (starring former Nazi propagandist Howard W. Campbell) and God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, particular favorites.

At the time, Vonnegut was still about five years from mass popularity and acclaim, which would only come in 1969 with Slaughterhouse-Five. This was the era of the “Vonnegut cult.” Kids trekked to Barnstable on Cape Cod to knock on his door or camp on his lawn. Graham Greene had called Cat’s Cradle one of the best novels of 1963 “by one of the most able living writers,” but few others of his rank volunteered similar views.

Vonnegut wasn’t taught widely in schools, if at all, still largely viewed as merely a “black humorist” or science-fiction writer (when he was viewed at all), but young folks were embracing him and his offbeat view of the world—an odd blend of idealism and cynicism. After consuming Cat’s Cradle we debated what was, and was not, a granfaloon (a group of people who claim to have a shared identity or purpose but whose association is actually meaningless). Since Dr. Strangelove was my favorite movie, clearly I was destined for this cult.

Like most readers, I didn’t know much about the author’s background (this was decades before the Internet) beyond the fact that he once worked for General Electric in Schenectady, N.Y., and now lived on the Cape. Actor Peter Fonda would later recall visiting the author around that time:

The rights to writer Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle had lapsed … so I phoned Kurt and made an appointment to meet him at his home on Cape Cod. To me, Cat’s Cradle was the perfect book to put into motion picture form…Kurt met me at the airport and we had some oysters, a delicious clam chowder and several martinis…

At Kurt’s request, I stayed at his house for three days, enjoying his life. I tromped through the muddy sand in the marshes with the gang, as we hunted the prized steamer clams for a big barbecue. The house was full with Kurt’s children and his late brother’s children, and I stayed in the barn.…At one point, Kurt invited me into his study, inscribed a copy of Cat’s Cradle and fished a joint out of his desk while asking me not to tell the children.

Vonnegut was no kid himself, that’s for sure. The name of his continuing character, failed sci-fi writer Kilgore Trout, was a take-off on author Theodore Sturgeon. And that was about my sum of knowledge.

When I got to college, other “darkly humorist” writers emerged, such as Joseph Heller and John Barth, but Vonnegut remained a favorite. One could, and did, re-read Cat’s Cradle almost every year. Still, it was a surprise when Slaughterhouse-Five generated raves from mainstream critics and sold very well, and earned a National Book Award nomination, with a major movie based on it, directed by George Roy Hill, on the way. Of course, this novel had a more serious, and personal, historical angle, as Vonnegut at last drew on his experiences in Dresden as a prisoner of war during the fire-bombing of the German city during World War II. But he also included his trademark sci-fi touches, in the guise of aliens from Tralfamadore and (maybe) the end of the world. Perhaps that’s why Jack Richardson in The New York Review of Books mocked it.

In-depth interviews with Vonnegut, particularly for TV, still were rare, although I read that he was working on a novel, Breakfast of Champions, and an antiwar play. One had to laugh about the latter, recalling Bokonon’s claim in Cat’s Cradle: “God never wrote a good play in his life.”

By mid-autumn of 1970, Vonnegut’s promised play, Happy Birthday, Wanda June, was about to open off-Broadway, at the Theater deLys on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. It would star a famous Hollywood actor, Kevin “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” McCarthy, plus the then little-known Marsha Mason and quirky character actor William Hickey. (Dianne Wiest was Mason’s understudy.) Since this was Vonnegut, the play's publicist did not shy away from publications with names like Zygote, or worse. I was invited to a group interview, sharing the thrill with a bunch of other semi-freaks from the alternative or college press, one afternoon at the theater. This would be the highlight of my professional life, for a few months, at least.

The play, nevertheless, would prove a bit disappointing, when I attended a preview. It was neither as funny as Cat’s Cradle nor as gripping as Slaughterhouse-Five (while retaining their antiwar themes). It certainly had its moments, but critics would act conflicted when it opened. The powerful Clive Barnes of The New York Times found it a weak piece of theatre but called it “diverting” with a lot to laugh and think about. He referred to the author as “the novelist and youth folk-hero…a master of sophomoric wit carried to the pitch of graduate hysteria. He dares jokes that few out of college would risk, which doubtless makes him adored by students…In part his brilliance might be seen as arrested intellectual development, but he can be richly and often pertinently funny.” Walter Kerr, also in the Times, hailed the play’s imagination and ideas but compared it to a “Punch and Judy” show.

A Times piece by Patricia Bosworth found Vonnegut admitting that he got shit-faced drunk on opening night, expecting the worst from reviewers. Indeed, the Clive Barnes claim that he was “sophomoric” really stung, he said. “If there’s one thing I’m not, it’s sophomoric,” he complained. He also promised to finally write something with a woman as lead character, calling “Women’s Lib” the “only hope for man’s salvation.”

The setting for Wanda June: The living room of a war hero turned big game hunter named Harold Ryan (McCarthy), who clearly represents the good old macho USA. He has been missing for years in the jungle. A search party is led by slightly dim-witted Col. Looseleaf Harper (Hickey), the man who dropped the atomic bomb over Nagasaki. He’s the funniest character in the play, oddly enough. Harper’s response to every question is “I don’t know, you know?” even regarding the tragic Nagasaki attack: “It was a bitch, but I don’t know.” (A quarter-century later, Vonnegut himself would declare: “The most racist, nastiest act by this country, after human slavery, was the bombing of Nagasaki.”)

Two suitors are after Ryan’s wife (Mason), who naturally is named Penelope, as the Odyssey parallels become obvious. One of the suitors is a cynical Vonnegut stand-in who is fiercely against violence and American concepts of manhood and heroism, while the other apes, so to speak, the missing husband. Ryan’s son, naturally, idolizes Dad in his absence. This being Vonnegut, there’s a side plot, set in heaven, where a little girl, Wanda June, has been sent after getting hit by an ice cream truck—on the way to her birthday party. It’s a pleasant place, where everyone plays shuffleboard, even Jesus H. Christ, who wears a “Pontius Pilate Athletic Club” warm-up jacket.

Meanwhile, Harold Ryan, rescued by Looseleaf, returns home to a less-than-hero’s welcome. His wife, a former waitress, has grown a lot, having gone back to college to earn her degree, and refuses to simply screw him on demand. The antiwar suitor heckles Ryan. His son—mirroring the youth of the 1960s—starts to see him as a blowhard. Mom tells Dad, “The young people today aren’t going to pick up a gun and kill just because you tell them to.” Looseleaf begins to have some doubts about bombing Nagasaki.

Ryan warns the others how dangerous “a wounded animal” can be. And he does end up shooting one of the suitors. (This was, incidentally, just a few months after the Kent State massacre.) The play ends with Wanda June and the cast from heaven stepping forward to sing a pacifist poem by John Greenleaf Whittier. One of them is wearing a Harold Ryan Fan Club jacket—with a yellow streak up its back.

My lengthy article for Zygote was published in its December 18, 1970 edition. Titled “The Benign Lies of Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.,” it opened with my assessment of his career, a review of his novels (going as far back as Player Piano and The Sirens of Titan), and a summary of Wanda June. It closed with a partial transcript of our “rap session” with Vonnegut which, thankfully, had proved quite revealing and humorous, as he spoke more frankly that I’d ever witnessed in his print interviews.

Do you feel that Nixon is pushing the youth revolution by the way he’s acting?

Undoubtedly. The trouble with Nixon is: He has no stage presence. He doesn’t comfort us like a father. He’s more like the bratty little brother you’re always trying to get rid of.

Next: The rest of the Q & A with the famous author.

Song Pick of the Day

One of Beethoven’s (i.e. anyone’s) greatest pieces, the “Benedictus” from his Missa Solemnis, Lenny conducting here, for Easter.

“Essential daily newsletter.” — Charles P. Pierce, Esquire

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including the bestseller The Tunnels (on escapes under the Berlin Wall), the current The Beginning or the End (on MGM’s wild atomic bomb movie), and The Campaign of the Century (on Upton Sinclair’s left-wing race for governor of California), which was recently picked by the Wall St. Journal as one of five greatest books ever about an election. For nearly all of the 1970s he was the #2 editor at the legendary Crawdaddy. Later he served as longtime editor of Editor & Publisher magazine. He recently co-produced a film about Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.