Running With Bruce, Down Thunder Road

More early Springsteen days--from baseball, Blavat and Blauvelt to Roy Orbison singing for the lonely: Another episode from my memoir-in-progress.

On the weekends we go longer and deeper, so here is another mini-chapter as we skip around my years before and during my Crawdaddy 1970s. So far we have re-visited my first Dylan concert in 1965 and initial encounter with Kurt Vonnegut, my hiring at Crawdaddy, driving with Springsteen to my hometown, interview with Ray Davies, and more. Now a look at The Man Who Would Be Boss, 1973-1975. (And here, again, is my little video on how we met Bruce in 1972—in Sing Sing Prison—and published the first major piece on him.) Thanks to those who shared yesterday’s edition. And if you haven’t, subscribe—it’s still free. For newcomers, my bio, links to some of my books and new film way down below.

You Go, Boss: 1973-1975

For several weeks in 1974, while researching and writing my profile of boyhood idol Roy Orbison—after interviewing him in Chicago at the lowest point of his career—I dove back into his vintage hits and was hyping him to all of my friends. One of them, fatefully, was Bruce Springsteen.

A year before his Born to Run breakthrough, Brucie was still far from a household name. Let’s put it this way: No one called him “The Boss,” except a couple of his band members, and not always with affection. He continued to provoke a rapturous response to his live show, but his second lp, The Wild, the Innocent and the E-Street Shuffle, had inspired mixed reviews and so-so sales. My rave for that record in Crawdaddy, I was told by one inside source, had helped convince Columbia to not drop him from the label.

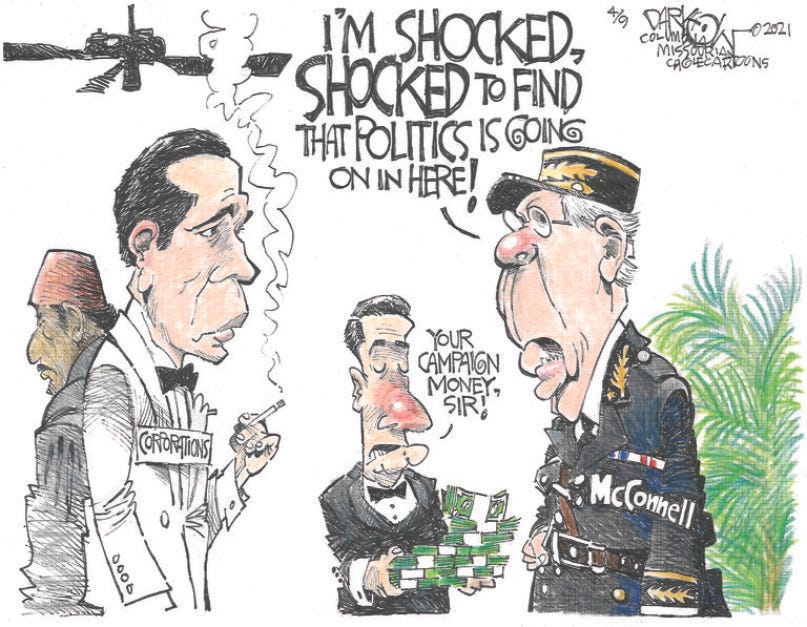

That meant they still owned him when Jon Landau wrote his career-changing “I’ve seen the future of rock ‘n roll” review after catching Bruce at last in a Boston club. Even then Columbia didn’t know quite how to promote him. They created this little promo video, below, but kicked it off with one of his earliest, far-from-rocking songs.

A few times, Crawdaddy editor Peter Knobler and I tooled up the Palisades Parkway to visit Bruce at the 914 Studio in tiny Blauvelt, N.Y., where he recorded his first two albums and was starting Born to Run. Work was going very slowly and members of the band sometimes slept overnight in the parking lot. At least there was a diner almost next door. (In an amazing coincidence, fifteen years later I would move out of NYC with my wife and son, to a house just over the hill from the long-shuttered studio, which had become an auto shop. There’s now a historical marker at the site noting its Bruce heritage.) Then Landau started to seize production duties from Mike Appel and shifted the recording to Manhattan.

Before the release of the hit Born to Run album and Time and Newsweek covers, I’d scurry down to the Jersey Shore to hang out with Bruce a bit. One weekend we got up at 5 a.m. to trek out to the famous flea market in Englishtown where we both bought boots. (His fit better than mine, good for him.) That night we hit a late show in Asbury for the concert film, Let the Good Times Roll, starring Fats Domino, Little Richard and other ’50 stars—Brucie’s favorite musical era.

Another night, with Peter Knobler, we drove towards Philly to visit a club where Miami Steve Van Zandt, who had not yet joined Bruce’s band, was playing with The Dovells (of “Bristol Stomp” fame). When we arrived there was this quirky surprise: The club, which had seen better days, was managed by one of Bruce’s boyhood DJ idols, Jerry “The Geator With the Heater” Blavat, now in his late-30s. The Geator was also spinning tunes between sets.

Blavat, you might say, was the original “Boss,” as his original nickname, I was informed, was “The Big Boss With the Hot Sauce.” He had hosted local TV shows then put in a stint as comedian Don Rickles’ valet—you can’t make this up—before becoming a kind of radio icon in Philly.

Only about three dozen brave souls were in the audience, but band members were still flirting with the young women crowding the stage. Van Zandt was dressed in a cheap white suit and fedora, and mugging right along with the Vegas wisecracks from the lead singer (better company and pay days were to come for Stevie). The rail-thin Geator was also playing to the crowd, sending out soul, Motown and Spector tunes to “The girls from Morristown!” among others between sets. Suddenly he shouted out to the beefy bartender, “Macho Joe!” Or was that “Nacho Joe”? Then: “Fur burgers! All you guys got to see these girls from Morristown!”

As the Dovells moved back to the stage, Brucie approached the Geator, reached out to shake his hand and introduced himself—after Blavat failed to recognize him. Following a brief chat, the Geator was now pumping Bruce’s hand and pounding him on the back, announcing to the crowd, “Girls, we got a star here! My man, my man, Bruce Springsteen!” A few minutes later, Bruce told us that he sensed Blavat still did not know who he was but had invited him on his local TV show that week. Small potatoes but he called it, with that big Brucie laugh, a “once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

The next night, Bruce (after a day on the beach) was planning to guest star unannounced at gig by the Blackberry Blues Band—fronted, pre-Jukes, by old friend Southside Johnny Lyon--at the legendary Stone Pony in Asbury. Bruce, of course, had navigated every nook and cranny of the place just a few years back. Hearing the rumors of Springsteen’s appearance, hundreds filled the place, including old friends from back in his scufflng days with names like “Hot Keys” and “Tinker” and “Albany Al.” Bruce eventually took the stage, backed by Johnny and Vini “Mad Dog” Lopez (who had been kicked out of the original E Street Band awhile back), among others. Fans cried out for some of Bruce’s own tunes, but he stuck to oldies but still goodies from the likes of Chuck Berry and The Beatles.

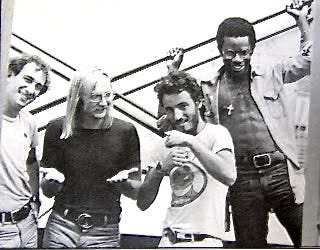

Then there was the rather infamous concert at Central Park’s Wollman Rink, where Bruce (loved at least in the Big Apple) opened for popular songstress Anne Murray. Davy Sancious on keyboards and drummer Ernest “Boom” Carter had just joined the band. Bruce put on his usual rockin’ good show, and left his many fans satisfied, who then left in droves, forcing the embarrassed headliner to face a two-third’s empty venue and, later, some mockery in the press. (Photo below backstage just before that historic gig.)

On one of my solo visits to Bruce’s apartment in Bradley Beach, he sat at a cheap upright piano and knocked out a bit of the tune that would become “Born to Run.” To illustrate how the guitar for it should sound on record, he played an old Searchers song on his cheap phonograph, maybe “Every Time You Walk Into the Room.” He vowed that “Born to Run” would be his first Top Ten smash, or he’d die trying. (It was, and he didn’t.)

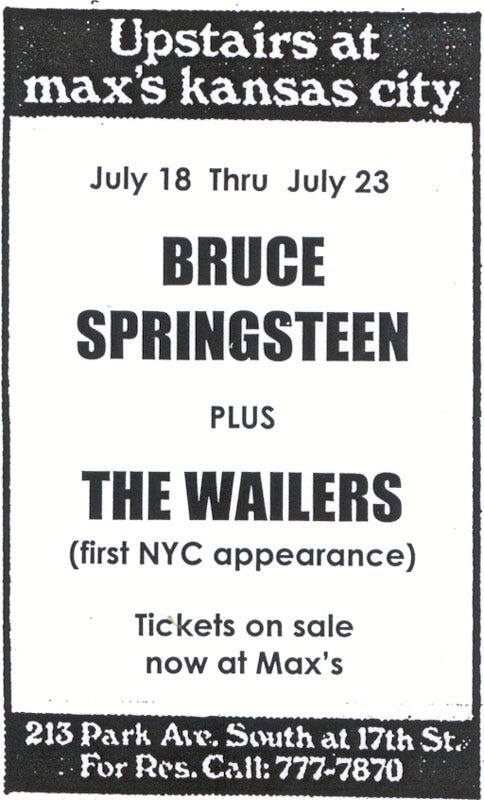

Another highlight: For several nights, Brucie and band shared a stage at tiny Max’s Kansas City with another about-to-break-through act: Bob Marley and the Wailers. Surely it was the greatest double bill I’d ever (and maybe would ever) experience.

On Bruce’s previous Max’s gig, he opened for pot comedian Biff Rose. After one night, Biff realized he could not to on after Bruce—or maybe he was just stoned—so he insisted on switching the order for the rest of the engagements. Now, a few months later Wailers were hotter nationally, Bruce more popular locally, so they took turns opening. I was there every night, of course. And Marley taught Bruce a thing or two about showmanship and charisma.

One of those nights, after visiting with Bruce in his dressing room upstairs, I strolled to the other end of the hall. There Marley and the boys were sitting on amps and equipment boxes smoking their trademark huge spliffs. Yes, Peter Tosh gave me a hit. Back in the sanctuary of Bruce’s dressing room: No pot there. In fact, to that point, I’d never seen Springsteen even drink a beer, let alone suck on a joint.

Equally memorable a little later: A touch football game with all of the E Streeters, plus Miami Steve and girlfriends, on a July 4 in Jersey. That night Bruce drove me back to New York with gal friend Karen in his classic ’56 Chevy convertible (yellow, as I recall), busting the speed limit continually. On another occasion, while I cowered in the back seat of a Jaguar with my date, Knobler challenged Springsteen (in a Galaxy) to a drag race on some dark, nearly-deserted Jersey highway. Bruce was up for it, and soon both cars were nearly hitting 100. Approaching a car in front, Knobler eased for safety, giving Brucie—who disappeared into the darkness on the edge of town—the win. (Here, again, my account of a quite different on-the-highway experience with Bruce.)

When Bruce was in Manhattan, visiting music stores or recording or stopping by the Columbia Records bunker, he would sometimes stop by the Crawdaddy offices down on Fifth Avenue, and Peter and I would entertain him for awhile. One day we had an epic “catch” with a tennis ball up and down West 13th Street as red-haired Karen watched, baffled. I finally learned what his line “Indians in the summer” from “Blinded By the Light” came from: The Indians were one of his Little League teams.

Later our Crawdaddy softball team would take on Brucie’s E Streeters in an epic doubleheader in Jersey. I suppose I will write about that soon, along with writing my first (and only) novel at Bruce’s house while he was touring UK and Europe after his Born to Run success.

One afternoon I took Springsteen to our room in back that had a sound system and played him most of the Roy Orbison’s Greatest Hits album. Of course, Bruce was familiar with many of the songs—and professed to love my Roy profile which by then had appeared in the magazine (and, yikes, Orbison had asked me to write liner notes for his next album). Like most people, however, he probably hadn’t heard most of his old hits in years. He was blown away, listened to all four sides, and a couple of songs again. Then I lent him my album.

Soon, via the Jersey grapevine, I learned that he had made a Roy tape off my album and was playing it on his tour bus all the time, leading to occasional complaints from E Streeters. Bruce started performing Orbison songs during his soundchecks and encores on stage. When I visited him backstage at, of all places, Philharmonic Hall in New York (he was opening for someone) he greeted me, from across the room, with the opening notes of “Pretty Woman” on the guitar: Da-da-da-da-dum, pause, pause, Da-da-da-da-dum. My new theme song.

The following year, lo and behold, what shows up at the start of the opening track “Thunder Road” on Born to Run? What was destined to be one of Bruce’s most quoted lines ever: “Roy Orbison singin’ for the lonely/ hey that’s me and I want you only.” I never got a chance to confirm my role in helping to inspire that—though they did award me a gold record for the album—but hey, that’s my story, and I’m sticking to it!

“Essential daily newsletter.” — Charles P. Pierce, Esquire

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including the bestseller The Tunnels (on escapes under the Berlin Wall), the current The Beginning or the End (on MGM’s wild atomic bomb movie), and The Campaign of the Century (on Upton Sinclair’s left-wing race for governor of California), which was recently picked by the Wall St. Journal as one of five greatest books ever about an election. His new film, Atomic Cover-up, just had its world premiere and is drawing extraordinary acclaim. For nearly all of the 1970s he was the #2 editor at the legendary Crawdaddy. Later he served as longtime editor of Editor & Publisher magazine. He recently co-produced a film about Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

The Bruce stories are priceless, and since I live right around the corner from Asbury Park, the locations are familiar.

Greg, Your "Running With Bruce Down Thunder Road" piece is fantastic. Memories and details as these--the Jaguar vs. Galaxy race; genesis of the "Born To Run" guitar sound; lending Bruce your Roy Orbison Greatest Hits L.P.; etc.--are legends not widely known in the Springsteen fan community.

On another note, I recently read your name being dropped in two Springsteen texts. One was in Ryan White's Album by Album book, in which Mike Appel, describes himself to Crawdaddy as "John The Baptist, heralding Bruce's coming into the world", etc. The second mention is in Clinton Heylin's, E Street Shuffle, where he writes, "Thankfully, Crawdaddy's ex-editor Paul Williams and current editors Peter Knobler and Greg Williams were almost in competition to see who could be more effusive about this New Somebody (Bruce)". Your work and passion continue.

I'll be sharing this site with two people tomorrow, thinking of more to add.