Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” “Atomic Cover-up” (on sale now for $1.99 as an ebook) and the recent award-winning “The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” He has directed three documentary films since 2021 for PBS (including “Atomic Cover-up”) . He has written about the atomic bombings for over forty years. You can subscribe to this newsletter for free.

2025 update: Trailer for my new film, narrated by Peter Coyote and coming to festivals this year.

The famed biologist Jacob Bronowski revealed in 1964 that his classic study Science and Human Values was born at the moment he arrived in Nagasaki in November 1945, three months after the atomic bombing (which killed at least 75,000 civilians) with a British military mission sent to study the effects of the new weapon.

Arriving by jeep after dark, he found a landscape as desolate as the craters of the moon. That moment, he wrote, “is present to me as I write, as vividly as when I lived it.” It was “a universal moment…civilization face to face with its own implications.” The power of science to produce good or evil had troubled other societies. “Nothing happened in 1945,” he observed, “except that we changed the scale of our indifference to man….“

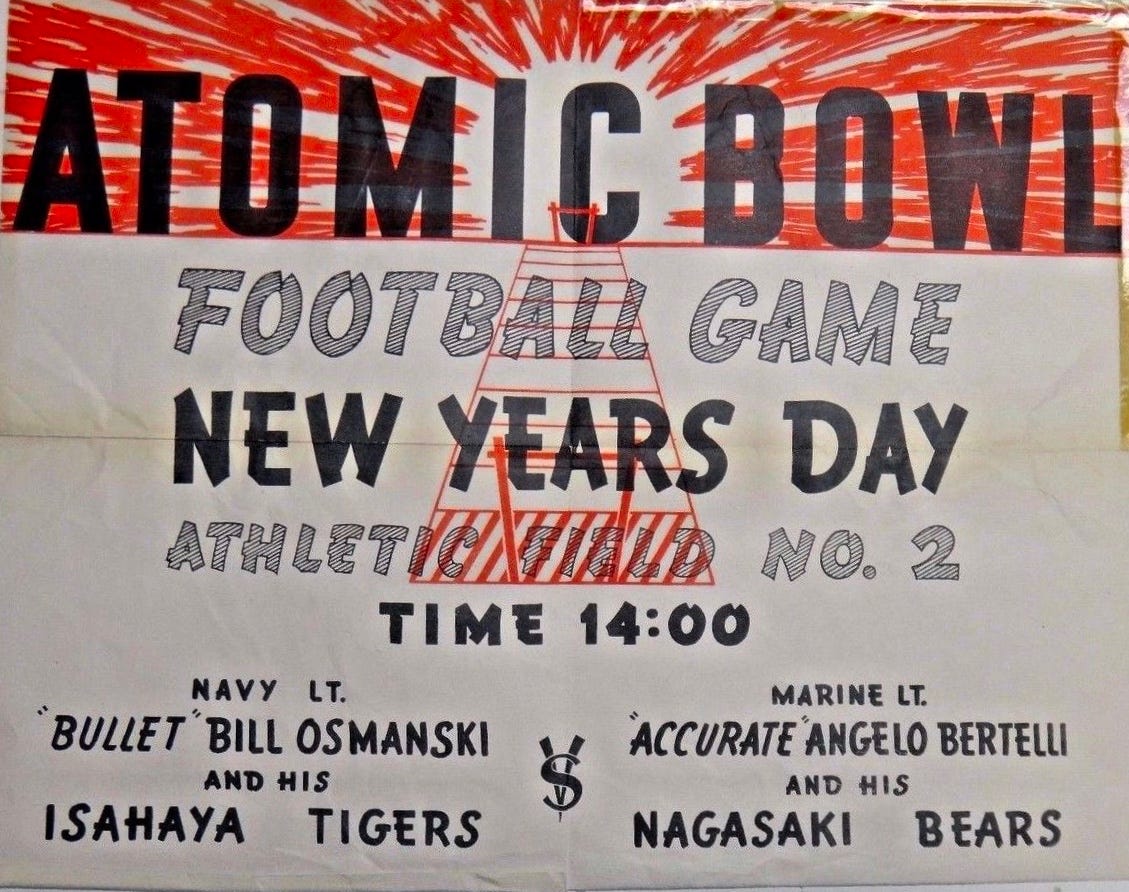

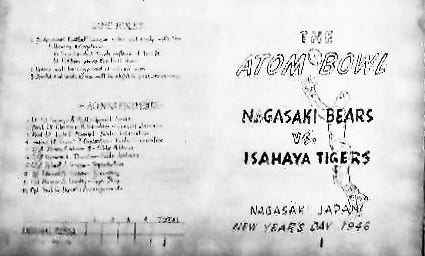

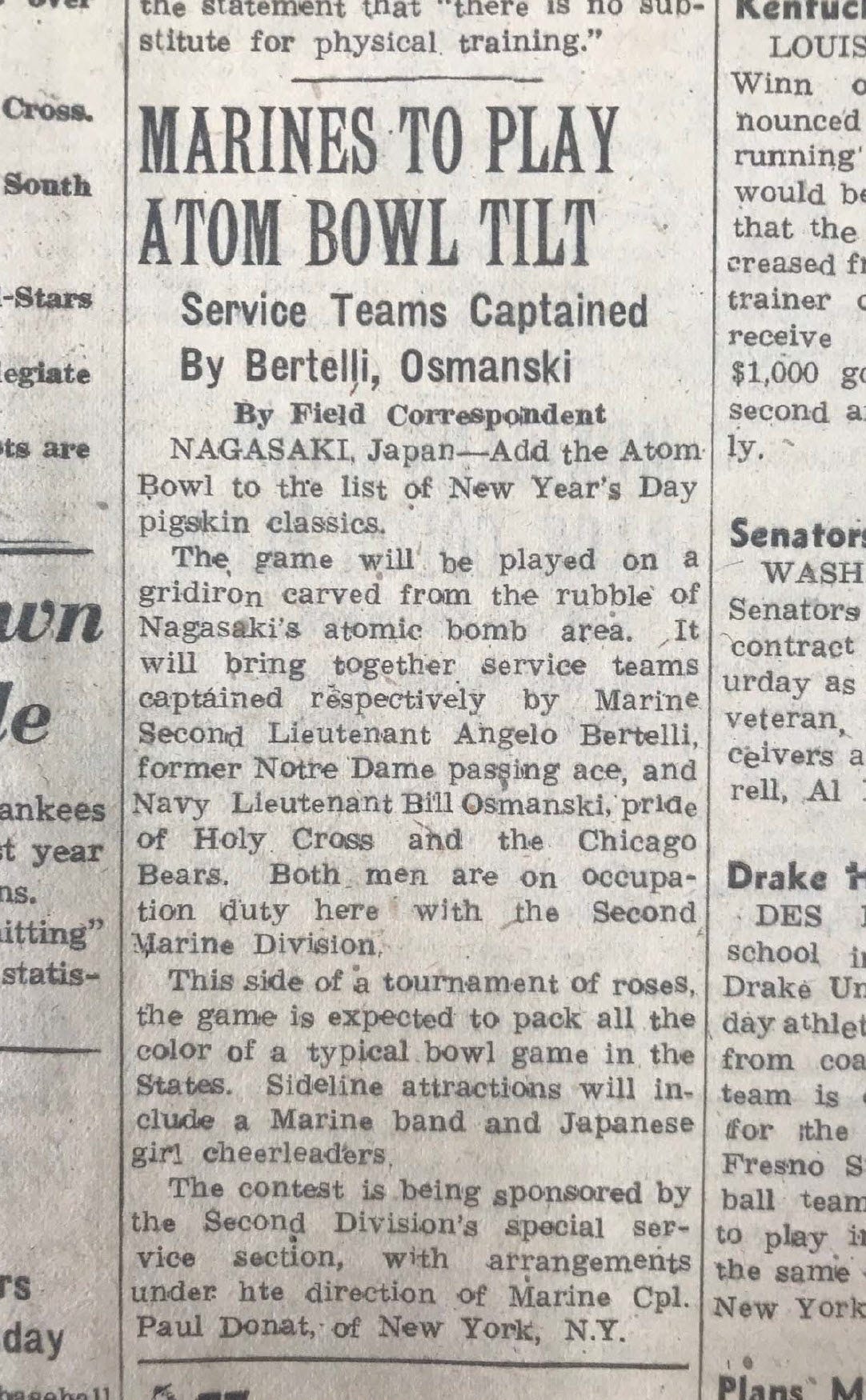

One of the most bizarre episodes in the entire occupation of Japan took place less than two months later, on January 1, 1946, in Nagasaki. (For more on this critical period, and my own experiences in Nagasaki, see my book Atomic Cover-up.) Back in the States, the Rose Bowl and other major college football bowl games, with the Great War over, were played as usual on New Year’s Day. To mark the day in Japan, and raise morale (at least for the Americans), two Marine divisions faced off in the so-called Atomic Bowl, played on a killing field in Nagasaki that had been cleared of debris (see link for footage of the grounds with goal posts below).

It had been “carved out of dust and rubble,” as one wire service report put it--without mentioning that it was the former site of a high school where hundreds of students perished on August 9--and was soon dubbed "Atomic Athletic Field No. 2." The report said it should be added to “the list of New Year’s Day pigskin classics.”

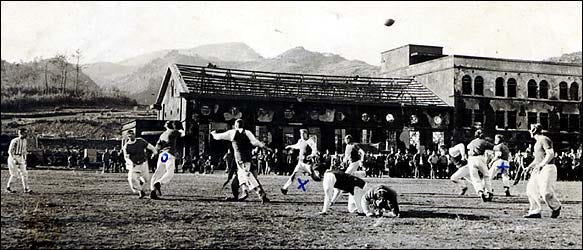

Both teams had enlisted former college or pro stars serving in Japan for their squads. The “Bears” were led by quarterback Angelo Bertelli of Notre Dame, who won the Heisman Trophy in 1943, while the “Tigers” featured Bullet Bill Osmanski of the Chicago Bears, who topped pro football in rushing in 1939 (and then became a Navy dentist). Marines fashioned goal posts and bleachers out of scrap wood that had been blasted by the A-bomb. Nature helped provide more of a feel of America back home, as the day turned unusually chilly for Nagasaki and snow swirled.

A band played the fight song, “On Wisconsin!” The rules were changed from tackle to two-hand touch because of all the irradiated glass shards from the atomic blast remaining on the turf. Two referees watched for infractions. Each quarter lasted ten minutes.

Press reports the next day claimed Japanese locals observed the game—from the shells of blasted-out buildings nearby. The two stars, Bertelli and Osmanski, had agreed to end the game in a tie so that both sides would be happy but Osmanski, after leading a second-half comeback, could not resist kicking the extra point that gave his team the win, 14-13. A commemorative booklet produced for the game included this line: "In the rubble of the atomic bomb, we made a gridiron.”

When servicemen stationed in Nagasaki returned to the U.S., a good number of them suffered from strange rashes and sores. Years later some were afflicted with disease (such as thyroid problems and leukemia) or cancer (such as multiple myeloma or forms of lymphoma) associated with radiation exposure.

One U.S. serviceman, a spectator, wrote this New York Times report in 1984.

My attention wandered from the field, out across the vast bowl of rubble to the ruins on the eastern horizon. The Yamazoto Elementary School, the Nagasaki Medical College, the College Hospital - all blackened shells staring through empty eyes. And dominating the scene on the slope of the hill was the great Christian cathedral, bowed down away from the blast in a chaos of scorched bricks.

Note: A former Marine named Bob Trujillo read my piece and sent it to a bunch of other Marines and the son of one of them responded with photos and a program for the game. I've now been in touch with the son and, yes, his father later suffered health defects he related to his atomic exposure in 1946.

»»»»My film, based on my Atomic Cover-up book, and now airing via PBS (watch here) and free at Kanopy, focuses on how the U.S. suppressed the most important film footage shot in Hiroshima and Nagasaki by a Japanese newsreel team and an elite U.S. Army squad. In reviewing dozens of hours of the long-buried color footage shot by our military, I was amazed when I came upon a very brief segment in which appeared the goal posts from the game left behind, with a wrecked building and devastated Nagasaki behind it. You can find it if you click that PBS link and go to the 12:48 mark.

·

Like many in my generation was raised in both fear of the bomb and a shared vindictiveness that excused its use in punishing (because let’s face it that’s so often the impetus for going to war - to make them hurt and to proudly stand over someone who you’ve just punched in the throat for hurting you or worse your sister brother mother father your home). Even now I take solace in the fact that American young men weren’t put through a meat grinder on the Japanese mainland defended by soldiers and citizens clasping the bushido requirement of Japanese soldiers to die taking as many of your enemies with you.

So we’re left with this tragedy we inflicted. Horrified and fascinated, like spying a car wreck from the back of your family’s station wagon on a highway travelling to visit a favorite uncle. Do we reject it wholly though? I don’t believe we do, like a condemned killer awaiting execution in a jail cell telling himself “I would do it again...”