When Peter Fechter Was Left to Die at the Berlin Wall

A true martyr of the Cold War, this week in 1962.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, writer/director of three films since 2021 (all airing on PBS), and longtime executive editor of the legendary Crawdaddy, 1971-1979.

___

It happened this week in 1962. This special post is drawn from my best-selling book, The Tunnels: Escapes Under the Berlin Wall and the Historic Films the JFK White House Tried to Kill—which I dedicated to Peter Fechter. A song tribute and trailer for the book at the bottom of the page. Subscribe, it’s still free. And one more note for those who are looking for (or thought they were subscribing to) my new “Oppenheimer and The Legacy of His Bomb” newsletter: here it is.

Last week, Germans and many others marked the 62nd anniversary of arrival of the Berlin Wall, a barrier that split that city from 1961 until 1989. Many factors combined to slowly chip away at, then end, the division of Berlin—and Germany itself—but one surprising element was the murder of a young man not long after the Wall rose.

“You can draw a direct line from the moment of Peter Fechter to the moment where the oppressed part of Germany collapses,” Egon Bahr, a top aide to former German chancellor Willy Brandt, said after the Wall fell in 1989.

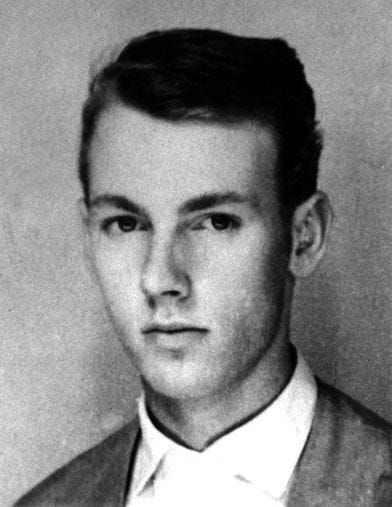

One might call Peter Fechter the martyr of the Cold War.

In the summer of 1962, Fechter, an 18-year-old bricklayer, was living with his family in East Berlin. He had a girlfriend but missed his sister, Lise, who had gone West in 1955, years before the Wall went up. The Communist state’s repression and lack of economic opportunity frustrated him. With friend and coworker Helmut Kulbeik, Fechter began planning an escape. The youths soon found a little-used factory near the Wall from where they might be able to navigate the barbed wire and climb the barrier to freedom.

The Wall was a crude affair of concrete and cinderblocks, topped by barbed wire and buttressed by cast concrete footings every few yards. West Berliners had built platforms from which to communicate with family and friends in the East. East Germany emphasized that regulations required guards to warn those attempting to cross into the West that they would be shot.

On August 17, 1962, Fechter and Kulbeik left their worksite at lunchtime. They decided this was the day to make a break. Saying they were going for cigarettes, the youths headed for their chosen location, on the border strip two blocks south of Checkpoint Charlie, main site of official transit between East and West Berlin. On the factory’s ground floor, they found a back room with all but one window bricked in. The small opening, crisscrossed with barbed wire, was letting in light. An East German guard post was a few hundred feet to the right, but the Volkspolizei, or VoPos, could not see the area outside the little window. Kulbeik and Fechter decided to hide in a big pile of wood shavings until evening, when dusk would provide cover.

Just before 2:00 p.m., the youths heard voices. Deciding to run for the Wall, they tore away the wire blocking the window. Peter squeezed through. Kulbeik followed, both landing in the VoPos’ blind spot. Hurdling a barbed wire fence with Peter in the lead, the two dashed across the death strip. The Wall was only ten yards away, but guards had seen them.

Without giving the warning their rules ostensibly required, VoPos with automatic rifles opened fire. Springing past Fechter, Kulbeik clawed his way up the eight-foot Wall and through the wire strung on Y-shaped brackets at the top. He was ready to swing over, only scratches to his chest, when he saw Peter below, probably paralyzed by the racket.

“Hurry up, go on with it, jump!” Helmut shouted, dropping onto the Wall’s western side. Kulbeik had gotten over on sheer momentum. Fechter was at a dead stop. All Peter could do was hide behind one of the narrow concrete supports jutting from the Wall. The supports only covered him on the right, but now he was under fire from the left. From their station VoPos Erich Schreiber, 20, and Rolf Friedrich, 26, recent draftees given little training, aimed about two dozen shots at Fechter. A 7.62mm steel slug from one of the guards’ Kalashnikovs hit Peter in the pelvis, exiting his body. Half a yard from the Wall, Fechter collapsed, bleeding heavily and screaming, “Helft mir doch, helft mir doch!” (“Help me, why aren’t you helping me?”).

Across the Wall, a West Berlin police patrol car arrived. Knots of West Berliners had gathered, anguished to hear Fechter’s cries. A cop shinnied up the Wall and stuck his head through the wire, but he and his colleagues had orders not to cross under any circumstances. He saw a youth lying on his back. Another officer tried to talk to Fechter. He threw bandages, but the weakened Fechter could only roll onto his side in a fetal position.

At 2:17 p.m. a U.S. Army lieutenant at Checkpoint Charlie phoned Major General Albert Watson, commandant of Berlin’s American garrison, for instructions. “Stand fast,” Watson said. “Send a patrol but stay on our side!” By the time six American military police arrived at the scene, about 250 West Berliners were there.

“You criminals!” they yelled. “You murderers!”

Bypassing chain of command, General Watson called the White House, asking staffers there what President John Kennedy wanted to do. Kennedy, in Colorado, listened to a clipped summary from his top military aide. “Mr. President,” General Chester Clifton said, “an escapee is bleeding to death at the Berlin Wall.”

At 2:40, half an hour after the first shots, a German interpreter for the U.S. military reported that a youth was “wounded and is lying against the wall on the east side. He is able to talk to the personnel on the west side of the wall.” West Berlin police requested an American ambulance.

Drawn by the gunfire, newspaper photographer Wolfgang Bera had run to the Wall’s west face. He found a ladder, placed it against the barrier, and climbed to where he could look down on the bleeding youth. Pushing a Leica through the wire, Bera framed Fechter, on his side, right arm outstretched and right hand open, palm full of blood.

Bera climbed down and, figuring the police paralysis on both sides meant that only the Americans could take charge, ran to Checkpoint Charlie for help. GIs on duty appeared indifferent. “It’s not our problem,” one said.

Freelance cinematographer Herbert Ernst joined the growing crowd of West Berliners as an American military helicopter circled overhead and American soldiers milled about. Ernst positioned himself on a viewing platform and, despite not knowing what was going on, began filming. East German guards fired tear gas canisters that landed near Fechter, perhaps to obscure him from cameras and onlookers or so they could retrieve him under cover of fog.

Returning to the Wall 50 minutes after guards shot Fechter, Bera made one of the Cold War’s iconic images: four border guards hauling away an inert Fechter. In another frame, Bera documented a single guard carrying Fechter.

Ernst captured the same moments on motion picture film, his camera eye following a VoPo taking Fechter under the armpits and another holding him by the feet—like a wet sack, it seemed to Ernst—and hurrying along Charlotten Strasse as a young couple loudly cursed the policemen and promptly were arrested.

Hearing nothing from Washington, General Watson again called the White House. “The matter has taken care of itself,” he told officials there.

By late afternoon hundreds of angry West Berliners had gathered near Checkpoint Charlie. Almost two hours later, two young East Berliners in a fourth-floor window near the checkpoint held up a small sign. An American interpreter signaled them to make a bigger sign. They did.

He is dead, the larger sign read.

West Berlin protesters that night came to number in the thousands. Many shouted “Murderers!” at three impassive East Berlin guards who stared back, pistols at the ready. VoPos threw tear-gas grenades over the Wall, triggering counter volleys by police in the West. Riots erupted. “Yankee cowards! Traitors!” the crowd shouted at Allied military policemen driving up in Jeeps. “Yankees go home!” Demonstrators smashed the windows of a bus bringing Red Army soldiers into West Berlin to change the guard at the Soviet war memorial in the British sector.

Stasi goons visited the Fechter family in Weissensee, demanding to know where Peter was. They searched the flat for weapons or incriminating literature but came up empty. Finally, the agents hinted obliquely that Peter might have been shot at the Wall that afternoon.

Peter Fechter’s murder hit West Germans like a punch to the heart. Das Bild, West Germany’s largest newspaper, ran Wolfgang Bera’s photo of guards hauling Fechter away as large as possible with the headline, “VoPos Let 18-Year-old Bleed to Death—As Americans Watch.” The same photo ran in Morgenpost beneath a banner reading, “Helft mir doch, helft mir doch!”

For inspiration, West German students digging a 400-foot escape tunnel under the Wall, the subject of my book—a venture underwritten by NBC-TV—hung photos of the dying Fechter in their cavern. Where Fechter failed, many of them succeeded. His story rippled far and wide. The New York Times front page carried a different Bera photo—two guards hauling the lifeless, unnamed victim—under the heading, “German Reds Shoot Fleeing Youth, Let Him Die at the Wall.” East Germany’s Neues Deutschland reported that two “fugitive criminals,” supported by West Berlin police, had tried to flee, forcing guards to resort to “use of firearms.”

An official autopsy done that day for the East German regime but not made public until years later found that among three dozen rounds fired in Fechter’s direction only one had struck him, suggesting that some guards deliberately mis-aimed. A rushed official East German report on the shooting found the guards’ actions “correct, effective and determined” and the use of weapons “justified.” Two VoPos who fired and two Volkspolizei officers received awards.

Returning from his trip, President Kennedy demanded explanations. “I would appreciate a detailed report on the refugee incident last Friday,” he wrote. “I would like to know how long it was before the Commandant was informed on what was happening and what action he took.”

Kennedy phoned Secretary of State Dean Rusk to ask what plans existed for handling similar situations.

“Well, we have some for larger episodes…” Rusk said.

“What about a single episode like this, though? “

“No one case is like another,” the Secretary of State said. “And the canals are…for example, our people don’t fish them out of the canals. That’s handled on the eastern side. I think perhaps the mistake that was made locally was not offering some medical care [to Fechter].”

“Yeah….Of course, the West Berliners are not very generous but…that’s all right,” Kennedy said. “I think we just have to ride through this one.” (My photo below of memorial to Fechter today on exact spot where he fell, with line of bricks showing path of Wall.)

Among those Peter Fechter’s death unsettled was Erich Schreiber, one of the guards who first fired at the young bricklayer, squeezing off 17 rounds in all. In a letter to his girlfriend, Schreiber wrote, “You write [asking] to know why I have been promoted. It is a more serious matter which does not happen to one every day. I have shot and killed a border violator who wanted to cross the border from East to West. If that would upset you and you don’t want anything to do with a ‘murderer,’ please do not talk about it with anyone. ” A censor intercepted the letter, which was never delivered. Schreiber mentioned the letter during a trial years after the Wall came down.

Ten days after the shooting, Fechter was about to be laid to rest. East German police tried to keep the funeral secret, ordering the family not to post any notice, but 300 citizens came to the funeral, at a cemetery near Fechter’s home. Some had worked with Peter; most were strangers. State officials nixed family wishes for a religious service, instead assigning a Municipal Funeral Commission speaker. He told those assembled Fechter had made a “thoughtless” and “foolish” decision. Everyone wishes to try different paths, the bureaucrat preached, but the state wisely promotes and then monitors which paths they should follow, and East German citizens must respect that. “But Peter did not,” he added.

Peter’s girlfriend and mother silently wept. Mrs. Fechter’s entire savings had gone for a coffin and wreaths; she had to borrow to get a tombstone inscribed Unforgotten By All. After the crowd left, Stasi agents cleared her son’s grave of flowers.

Helmut Kulbeik remained in the west, and is still alive. A memorial to his dead friend at the Wall in time would draw thousands of visitors and inspire books, poems, song, and theatrical presentations. Peter Fechter’s death stirred outrage that would simmer until the fall of the Wall, more than a quarter century after he made his run for freedom.

Here’s the trailer for my book, with a fine song by Patrick Ffrench, another tribute to Peter Fechter.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen nonfiction books, including Goldsmith Book Prize winner The Campaign of the Century, Atomic Cover-up, and Tricky Dick and the Pink Lady. Mitchell’s acclaimed bestseller The Tunnels: Escapes Under the Berlin Wall and the Historic Films the JFK White House Tried to Kill was published by Crown.