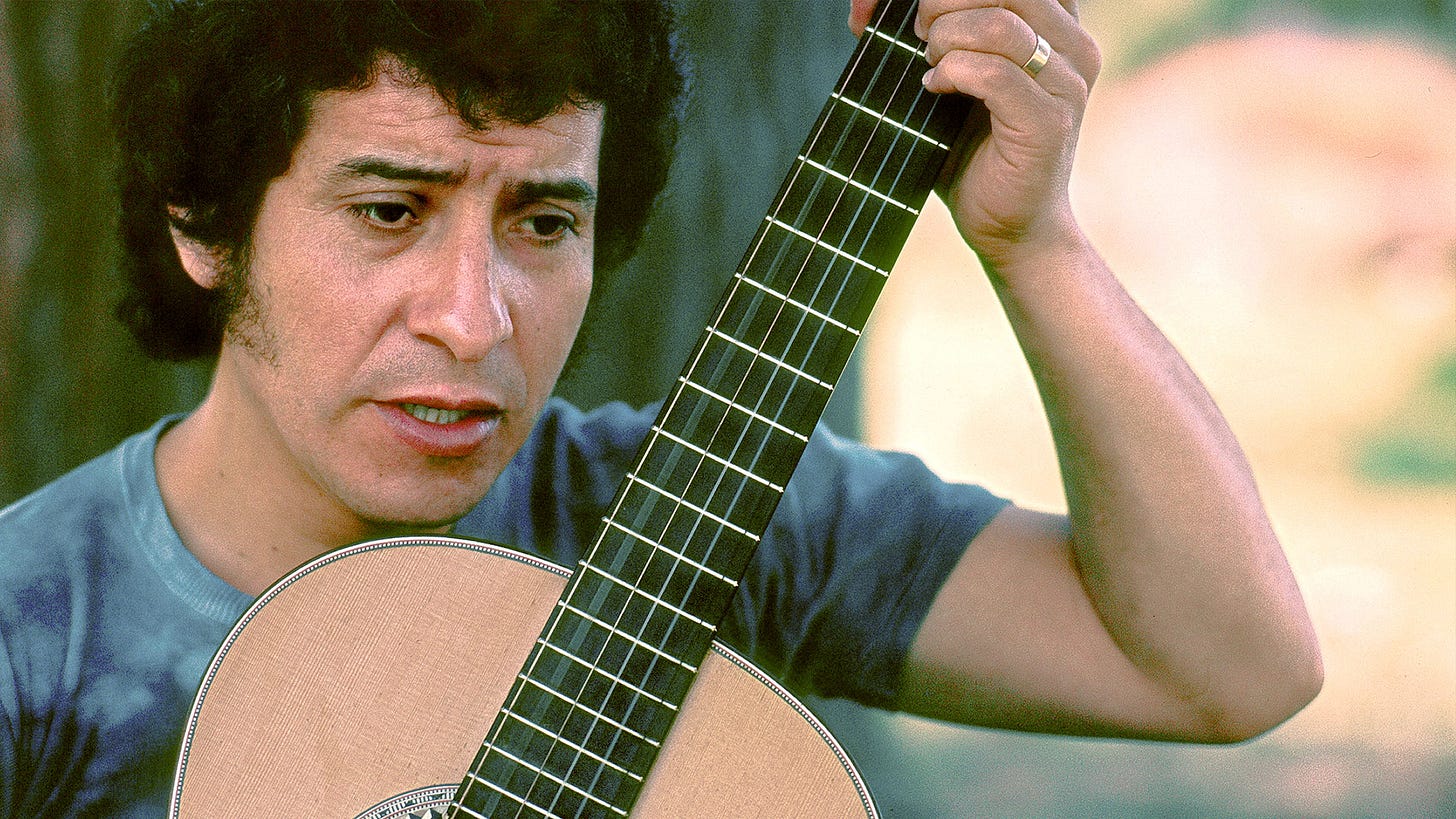

The Last Song of Chilean Folk Singer Victor Jara

Remembering the once-forgotten "Bob Dylan of Chile" who died, after being tortured, in the 1971 Pinochet coup.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books and now writer/director of award-winning films. He was the longtime executive editor of the legendary Crawdaddy. His newsletter remains free when you subscribe. His film “Atomic Cover-up” became free via Kanopy this month and the current “Memorial Day Massacre: Workers Die, Film Buried" remains free on the PBS site. Both have companion books.

Startling update today, Oct. 11, as soldier who murdered Victo Jara was arrested in Florida, as reported in The New York Times. Excerpt. And my post from just two weeks ago below.

A former Chilean Army officer accused of torturing and killing the Chilean folk singer Victor Jara and others during the bloody aftermath of a 1973 military coup was arrested in Florida, officials announced Tuesday.

The former officer, Pedro Pablo Barrientos, 74, who moved to Florida in 1990, is wanted in Chile for the extrajudicial murder of Mr. Jara at a Chilean sports stadium. There, Mr. Jara and other dissidents had been detained after the coup on Sept. 11, 1973, that toppled the country’s president, Salvador Allende, and thrust Gen. Augusto Pinochet into power.

Federal immigration officials and local law enforcement officers arrested Mr. Barrientos on Oct. 5 during a traffic stop in Deltona, Fla., about 30 miles southwest of Daytona Beach, according to a news release published on Tuesday by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

This month marks 52 years since the violent, U.S.-backed (thank you, Henry Kissinger) Pinochet military coup in Chile which ended the brief Socialist reign of popularly elected Salvador Allende. The tragedy has gained new attention with the recent release of the Pablo Larrain movie El Conde—in which Pinochet is portrayed as a 1000-year-old vampire—and the re-release of the epic documentary Battle of Chile, which I saw way back in the late-1970s (and edited a Greil Marcus review for Politicks magazine).

One of the most notable victims of the thousands murdered in the first days after the 1971 coup was the popular folksinger Victor Jara, sometimes called the Pete Seeger or Bob Dylan (during his ‘60s protest phase) of Chile. Yet for three years after, he was still little known in the U.S. and the details of his death debated or denied.

At Crawdaddy in 1974, we published the first major article about Jara in this country. It was only because our political editor, Stew Albert (a co-founder of the Yippies) had traveled to Chile, with folksinger Phil Ochs and Jerry Rubin, in the waning months of Allende’s rule. They spent a good deal of time with Jara, and Ochs sang with him. Albert eventually wrote his piece for us with grim new details about Jara’s death—soldiers had first crushed his fingers, taunting him with, “Now see if you can play your guitar.”

Ochs organized an “Evening for Salvador Allende” in the Felt Forum under Madison Square Garden, which I attended. Arlo Guthrie and Pete Seeger sang, Dennis Hopper spoke, and Dylan performed three songs (famously drunk, as it happens). Victor Jara earned several references. Later, both The Clash and U2 name-dropped him in songs.

Then he was largely forgotten in the U.S. for many years. Back in Chile, the Pinochet regime finally ended in 1990, and legal cases attempting to bring Jara’s murderers to justice began. Film documentaries about Jara and these cases appeared. This culminated in June 2016, when a Florida jury found former Chilean Army officer Pedro Barrientos liable for Jara's murder, which The Guardian called “one of the biggest and most significant legal human rights victories against a foreign war criminal in a US courtroom.” Two years later in Chile, eight retired Chilean military officers were sentenced to 15 years and a day in prison for Jara's murder.

What follows is an adapted version of Stew Albert’s report in Crawdaddy which I edited for our October 1974 issue, titled “The Last Song of Victor Jara.” Trailer for one of the Jara films below, featuring Bono, Arlo, Seeger, Judy Collins….

THE LAST SONG OF VICTOR JARA

"Victor Jara was murdered!" A friend I hadn't seen in over a year stunned me with the news. We had met Jara during our visit to Chile in the early days of the Allende experiment. Now we sat sadly side by side on a Catskills mountaintop. The death of the democratic socialist Allende in a bloody military coup d'etat was old news but Jara's death was not. "They killed Victor in the Stadium. His wife saw the body. It's really him."

Three years before we had watched Victor Jara perform at the Pena de los Parras, a club for Chile's most dedicated and talented folk artists. Jara was a folk singer like Pete Seeger or the early Dylan who set his poems and his political passions to music. His voice was strong, his face broad and exuberant. You never forget such a face. He sang of a priest who became a revolutionary:

My traveling partners were Phil Ochs and Jerry Rubin, all of us attracted to Chile because it seemed so hopefully unique, the first country to have a socialist revolution which was both peaceful and democratic. Were there lessons here for our own country?

Victor was a regular at the Technical University in Santiago, where he instructed in folk art and talked politics with the students. While captivating in its own right, his music was always used as an organizing tool. He was very glad to meet us. "Usually we Chileanos meet only bad guys from the U.S., like from the CIA," he observed, "but it's really nice to know we have some brothers up north."

He was delighted to discover Phil was a fellow folksinger: "You will have to come with me to the copper mine up in the Andes. It's just been nationalized and I am going to sing. Also some of my brothers from the University are going to have a basketball game with the workers. It would be very good to have a gringo like Phil Ochs to sing."

It was a long, bumpy bus ride to the Anaconda mine. Of the three North Americans, only I spoke a little Spanish, and Victor, who spoke perfect English, was deep in discussion with members of the basketball team. I could make out words like "spies," "agents" and "Nixon." Finally, Victor turned to us: "My brothers are a little bit mistrustful of you. They think maybe your long hair is some kind of spy's disguise. I am going to sing revolutionary songs. If perhaps you will join in with some enthusiasm, they will see your hearts are in the right place."

Victor began singing, and although the language was foreign the song's melody was strangely familiar. It was Pete Seeger's "If I Had A Hammer." We joined in with English words, trying hard to pick up a little Spanish in the chorus. We sang very loud, hoping by sheer volume to drown out the Chileans' suspicions. (Phil and Jerry, at right, with workers, below.)

As the bus pushed up into the mountains and the magnificent peaks began to disappear into the night, Victor began talking about his life and his dreams: "My songs, they are what I feel, they are about my life. But I am a peasant and so they are also about millions of people, about suffering, but also sometimes victory."

Victor was dark-skinned, and his muscles were built solid from hard labor. He translated from his songs, poetic lines, which showed how when a man reaches deeply and privately into his own heart he may discover the pain and suffering of most of humanity. "I try not to hate," Victor declared, "but how can you not hate such oppression?"

"Do you think Allende's approach will solve Chile's problems?" we asked.

"It is necessary for now for us to be peaceful, because the army has all the guns and they aren't friends of the poor. Maybe someday they will make the coup against us. I hope that we will be organized and brave to fight."

Victor's wise distrust of the military was not publicly shared by the Allende government, which regularly proclaimed "our profound conviction in the army's patriotism and loyalty." When we asked Jara about this, he replied, "Well, they are a government and what they say is public, and of course they don't want to antagonize the army. What I say here is private and among brothers.”

"Do you sing professionally, for money?"

"No, never. I belong to a movement, a generation of folksingers who never get paid. We make what we can from other sources but never from our music, which is after all the common property of the people's experience, so why am I somebody special to become rich?"

The mining town was surreal. It was built on the side of a mountain, without streets, and whole neighborhoods were above and below each other, linked only by steps. To get to the gym we had to walk up what seemed like thousands of them but the Chileans weren't even out of breath so we were too embarrassed to ask for rest. Sometimes our long hair was greeted with insinuating whistles from the miners.

"You shouldn't take it personally," Jara explained, "the only people who have long hair in Chile are the lazy rich kids, so it's a good experience for these men to meet someone with long hair who is a friend."

Both Victor and Phil sang. Victor's songs were stirring, but he could be playful, like when he sang a Spanish version of Malvina Reynolds' "Little Boxes." He had an incredible range of style and subject, and the miners would sometimes cheer and at other moments laugh. And he changed the words. Victor's "Little Boxes" was about a right-wing assassination of a loyal Allende general--it was folk music in its truest form, created by local experience and need.

Ochs offered his "I Ain't Marching Anymore" declaration of independence. He sang slowly and Victor would translate into Spanish. I don't think Phil ever sang to a more appreciative and supportive audience. After the performance, Victor introduced Jerry and me to the audience. At first everyone laughed or even hissed at our hair, but Victor pursued our defense: "These brothers have come a long way to be with us and to support our revolution. Are we going to make them think we are cold-hearted like the rich?"

Someone shouted "Viva los hippies buenos!" and everyone joined in.

Afterwards we went down the elevator into the mine. It was 2 a.m. and a group of miners who were just getting off their shift came surging out. Victor was stunned by the pain on their faces. He was in a controlled rage and his eyes filled with tears: "Look how human beings have been treated. They are made to have the expressions of animals. I tell you, man, we are going to make things different from now on."

The last time we saw Victor, he was standing outside a classroom at the University, the same University at which he was taken prisoner by the fascists during the coup. Victor was spending a lot of time there helping students bring food and fuel to the poor people, who were suffering from the CIA-sponsored strike of small businessmen. Food wasn't being distributed by the business interests so students were trying to feed as many as possible.

This is what Victor was devoting his life to when he was captured. He and 6,000 other Chileans were thrown into the National Stadium and kept under armed guard.

Miguel Cabenzas is a Chilean journalist. As a prisoner in the National Stadium, he witnessed the murder of Victor Jara. This account was translated by Leonore Veltfort.

Chaos, desperation, panic were all over. Unless one has lived through a scene like this one can't imagine the extent of people's collective madness when they are provoked by such incomparable terror. The prisoners were put in the bleachers of the stadium, and down below were the military. They focused strong lights on the prisoners. Suddenly, somebody began to scream with terror, having lost his mind. Immediately, machine-gun volleys were loosed against the section where the scream came. Ten or twenty bodies fell from the high bleachers, rolling over the bodies of those prisoners who had thrown themselves to the ground to avoid the shots.

Victor wandered around among the prisoners, trying to calm them, to keep a minimum of order among them. A fruitless attempt. The terror was limitless. It brought the prisoners to the lowest degree of human degradation. The military were determined to accomplish this, and after three days of detention and mass terror they did.

At one point, Victor went down to the arena and approached one of the doors where new prisoners entered. Here he bumped into the commander of the prison camp. The commander looked at him, made a tiny gesture of someone playing the guitar. Victor nodded his head affirmatively, smiling sadly and candidly. The military man smiled to himself, as if congratulating himself for his discovery.

A volley, and the body of Victor began to double over as if he were reverentially making a long and slow bow to his comrades. Then he fell down on his side. More volleys followed from the mouths of the machine guns, but those were directed against the people in the bleachers.

An avalanche of bodies tumbled down, down, riddled with bullets, rolling into the arena. The cries of the wounded were horrible. But Victor Jara did not hear them anymore. He was dead.

His body, with 40 bullet wounds and signs of torture, was then deposited on a shantytown street in Santiago.

A few months ago I attended a benefit in New York for Chilean Refugees, which was organized by Phil Ochs. It was a big event because Bob Dylan appeared, coming out of political retirement like he was back in his old hootenanny civil rights days. But the highlight for me was Pete Seeger reading a poem written by Victor and smuggled out of the Stadium shortly before his death. Pete's voice evoked the feelings behind Jara's words.

We are 5000, here in this little corner of the city.

How many are we in all the cities of the world?

All of us, our eyes fixed on death.

How terrifying is the face of fascism!

The words are from a brother telling exactly what is it like to die at the hands of devils, a warning from someone who welcomes death as a last escape but wants one last communion with the living. Victor Jara was 40 years old when he died.

Today, the struggle for democracy in Chile goes on, and in the fight guns are going to be used. This time it won't be non-violent. The generals and the CIA don't want the peaceful "Chilean Way" to work. The songs of Victor Jara will again be sung in a free Chile. But Jara's greatest poem is beyond the language of words. It was his death, and life.

Below: Phil and with Dylan and Dave Van Ronk, full concert here.

Arlo Guthrie’s song, “Victor Jara.”

I'm also familiar with Victor Jara by a song by the Clash, "Washington Bullets" in which Joe Strummer pleads, "As every cell in Chile will tell/ The cries of the tortured men / Remember Allende, and the days before, Before the army came /Please remember Victor Jara, In the Santiago Stadium,

Es verdad - those Washington Bullets again"

If only the true history were taught, no one would be shaming and rejecting immigrants trying to escape a land we destroyed