When Roy Orbison Sang for the Lonely

On interviewing one of my boyhood favorites. With a special appearance by Bruce Springsteen.

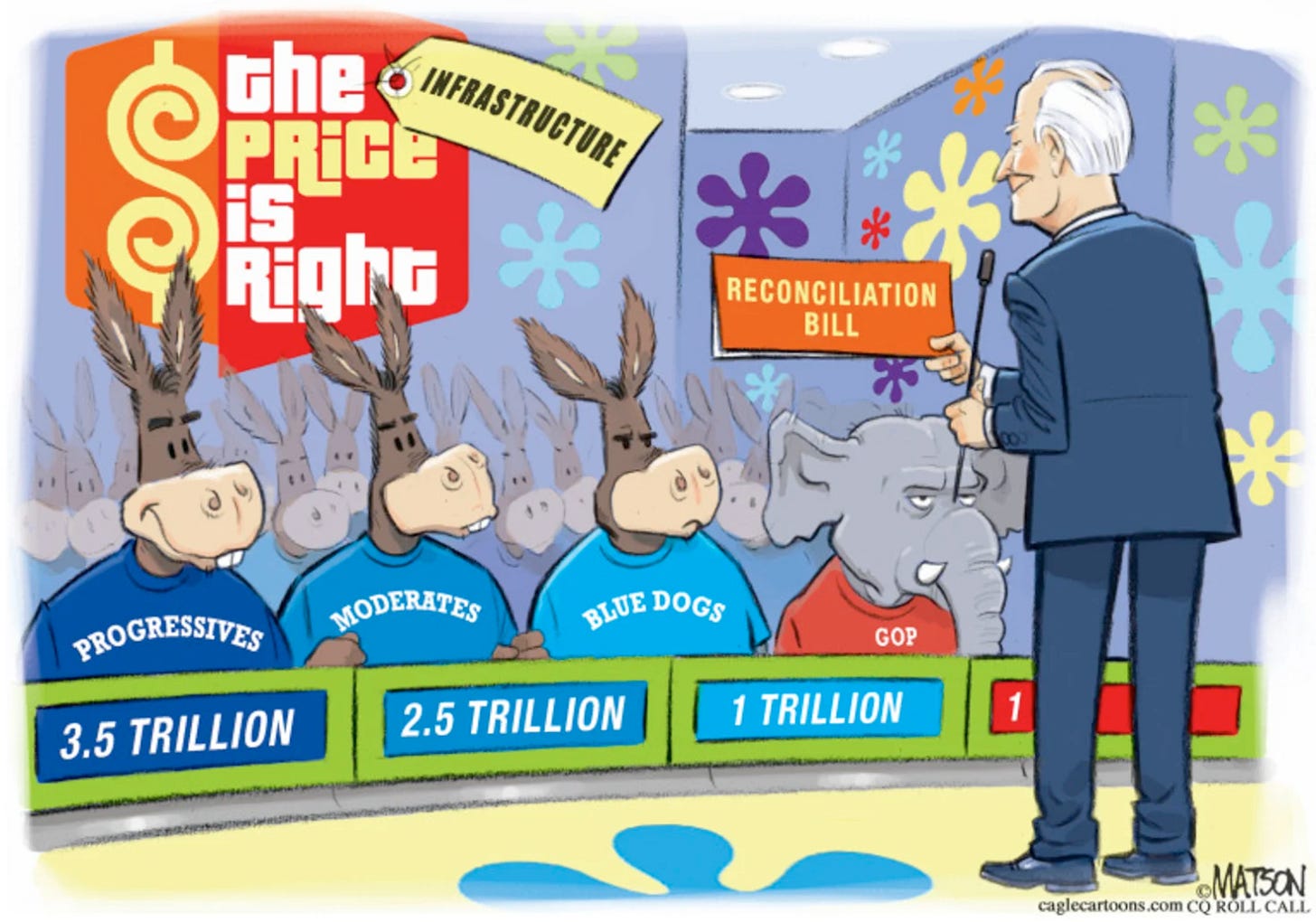

When I profiled Roy Orbison for Crawdaddy in 1974 (and then wrote the liner notes for his next album) he had disappeared from the rock ‘n roll charts for nearly a decade. Few, beyond Roy himself, imagined that a comeback, slow but certain, was just a few years off. First, Bruce Springsteen dropped his name in the opening to “Thunder Road”—for which I claim some credit (see Part II tomorrow). Linda Ronstadt covered his song “Blue Bayou.” A notorious scene in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet focused on Dean Stockwell miming “In Dreams.” Then Roy joined a few fellas named Dylan, Harrison, Petty and Lynne in the unlikely Traveling Wilburys (and also recorded a hit solo album). But I found him in Chicago at the lowest point in his career. Enjoy, then subscribe, it’s free. First, the usual timely cartoons to get started.

Running Scared? Not Roy Orbison

By 1974, one of the leading '60s hitmakers, Roy Orbison, had been lost in action for nearly a decade, at least for rock ‘n roll audiences. For me his mid-career collapse seemed as tragic as the lyrics of many of his songs. We went way back together.

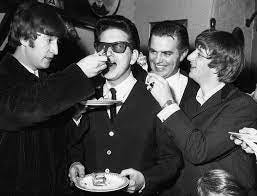

In the late-1950s, my favorite rocker was Ricky Nelson, partly because he co-starred in the TV comedy, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. By 1962, Roy had supplanted Ricky at the top of my pops. At the time, teen-oriented music was largely off its rockers. Buddy Holly had died. Chuck Berry had been thrown in jail for taking a teen across state lines, and Jerry Lee Lewis never recovered from the public relations disaster of marrying his cousin –- also a young girl. Little Richard, always outrageous (and seemingly gay), was about to become a preacher. The Beatles, who opened for Orbison in a major tour of the UK—John Lennon called Roy his favorite singer—had not yet arrived on our shores.

There was no mistaking Roy on the radio. He could hit the highs, lick the lows and invigorate the in-betweens. His lyrics were always spooky, from the despair of “Crying” to the tortured triumph of “Running Scared.” He was the Caruso of rock. You knew that almost without fail that he was going to wail, and when he did, your car radio or transistor speaker was going to tremble like a windowpane caught in high-C hurricane.

It was a voice from the other side, unearthly in the majesty of its emotion, almost oppressively powerful, yet in the end fragile, sadly human. Only the lonely knew the way he felt that night. “Love Hurts” might have been his theme song not just a memorable B-side. With Elvis slumping, as he concentrated on Hollywood (and shagging starlets), the singer/songwriter from Wink, Texas, had become the number one male vocalist in the rock world. He even delivered “Pretty Paper,” a new Christmas classic. The Beatles covered one of his songs live. The Stones loved him. (“Running Scared” and “Crying” below, 1965—no lip sync needed.)

Along with a few others in junior high, I formed the Western New York chapter of the Roy Orbison fan club. The national fan club president sent us a list of duties, including calling DJs every week to hector them about playing Roy; or holding a “Coke Party” to attract new members. The orders ended with #5: “Most important—do all of this with gestures of such good taste and refinement that nothing will blemish or impair our star’s person or work.” This hardly seemed like the spirit of rock ‘n roll.

In any case, we didn’t do a damn thing, except buy his records.

And now, a decade later? For all I knew, Roy was crying or running scared out in the rock ‘n roll wilderness. His early hit “It’s Over” seemed more haunting every year. In reality, he had never stopped releasing albums and touring. True, the albums, aimed more at a country audience, all stiffed and the concerts were mainly abroad, where he was still popular. In the mid-1970s was there still life in the old boy—ten years after he growled at a “Pretty Woman”? (“Oh, Pretty Woman” live, below, from 1964 when it knocked the Beatles out of #1.)

Not sure how it happened, but it came to my attention at Crawdaddy, where I was the second-ranking editor, that Roy had finally signed with a new label, Mercury, after nearly a decade with faltering MGM, the label that had help drive him off the rails. When I contacted Mercury’s publicity director, he told me Roy was going to Chicago to talk to the press about an upcoming “comeback” album. Would I like to meet him there?

Naturally, I said yes. What a story. Roy had started at Sun Records with Elvis and Jerry Lee and Johnny Cash, sold 30 million records, and helped keep rock alive in the early 1960s. On the other hand, he’d lost his wife in a motorcycle accident—he wrote a hit for the Everly Brothers with her name, Claudette, as the title—and two of their kids in a fire, and he hadn’t been high on the charts since 1965.

In Chicago—my first trip there since surviving the 1968 Democratic convention and “police riot”—the publicist introduced me to a very polite Orbison, already in trademark sunglasses on a dark night, at the hotel. Then we drove off together in a limo to dine with Mercury execs and then hit a club show starring Ray Manzarek, the former keyboard hinge of the Doors.

It turned out that the “Caruso of rock” was incredibly soft-spoken. “Oh, isn’t that awful?” Roy asked incredulously, barely glancing at the old, wrinkled fan club photo that I produced out of my shoulder bag. Actually, he didn’t look all that different from the guy in the photo, except he’d put on a few pounds, was wearing shades instead of horn rims, and had combed his pompadour over his forehead, as if still paying homage to his friends, The Beatles. (Below, Roy a couple of years before our meeting, singing “In Dreams”—long before it played a key role in Blue Velvet.)

When we got to the restaurant, the P.R. guy pulled me aside and advised, “Keep it clean—they tell me he’s very religious. And don’t mention the accidents [involving his wife and kids]. They really destroyed him.” The dinner took place on the 91st floor of the new John Hancock building. Someone from Mercury pointed to a large round spitball on the ceiling, courtesy (he said) of another act on the label, Rod Stewart. The menu was in French. “I’m generally satisfied with cheeseburgers,” Roy revealed.

Then it was off to a Gold Coast club called PBM for Manzarek and his loose, probably drunken, set. Joining the entourage was speedy Danny Sugerman, a former rock writer who had managed the Doors after Jim Morrison’s death and was now writing lyrics for Manzarek. (Danny would later pen a bestselling Doors bio, manage Iggy Pop, and marry Fawn Hall—yes, that Fawn Hall, of Oliver North fame—before passing away at the age of fifty.) Roy chatted with one of the other members of our group about the cult Antonioni film, Zabriskie Point, which kind of surprised me. Roy a cineaste?

In the limo ride back to the hotel, Roy said that his musical tastes these days ran to soft-rock or country, and mentioned Olivia Newton-John and Barbara Fairchild. “Nobody fractures me,” he said. He had recently attended a concert by his old buddy Elvis Presley in Tennessee, and “it was terrible.” As for Roy’s sets, “Some of those old songs are bad but we do them bad like they were.” But he still sang “Crying” as if for the first time: “I think the secret to my lasting success is that I’m not trying to be too clever, too progressive.”

Then there was this anecdote: He once made a backstage deal with the Rolling Stones in London before they came to the U.S. He would sing his worst song, “Ooby Dooby,” from his early Sun days, that night if they would do their worst song. He kept his end of the bargain—they did not. “So to make up for it,” he added, “Mick gave me a silver cigarette case inscribed with Ooby Dooby.” (Roy would later send me a rare 78 copy of the song.)

The cab ride was mercilessly cut short by our arrival at the hotel. We made plans for meeting the next morning. It was only 11:15, but Roy argued, “I’ve got to go beddy-bye now if I’m going to be any good for you tomorrow.”

Tomorrow: Part II. The interview, and then how I fatefully connected him to Springsteen (and see below).

“Essential daily newsletter.” — Charles P. Pierce, Esquire

“Incisive and enjoyable every day.” — Ron Brownstein, The Atlantic

“Always worth reading.” — Frank Rich, New York magazine, Veep and Succession

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including the bestseller The Tunnels (on escapes under the Berlin Wall), the current The Beginning or the End (on MGM’s wild atomic bomb movie), and The Campaign of the Century (on Upton Sinclair’s left-wing race for governor of California), which was recently picked by the Wall St. Journal as one of five greatest books ever about an election. His new film, Atomic Cover-up, just had its world premiere and is winning awards. For nearly all of the 1970s he was the #2 editor at the legendary Crawdaddy. Later he served as longtime editor of Editor & Publisher magazine. He recently co-produced a film about Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

You need to know that at the end of each of your music post , I myself with a big smile on my face. Thank you!